The Danish Invasion The Danish Invasion

Quick links on this page

Death of King Edmund 869

Partition- England/Danelaw 878

Saint moved to Bed'sworth 906

Mercia broken into Shires 920

Bury given to the monks 945

Abbo's Life of St Edmund 985

Battle of Maldon 991

Danes cause saint's move 1010

King Canute takes over 1016

Benedictines come to Bury 1020

Round stone church built 1032

W Suffolk given to Abbey 1044

Baldwin comes to Bury 1060

Foot of Page 1066

|

From the

Viking Invasion

to the

Norman Conquest

|

Pre 865

|

Please click here if you want to look back at the Early and Middle Saxon periods of our history. Now begins the Late Saxon era.

|

|

865

|

Modern historians refer to the 200 year period after 865 as The Late Anglo-Saxon time. This is because the year 865 heralded disaster for Anglo-Saxon England. It was the year of full scale invasion by the Great Army of the Danes.

The year began with a Danish army having over-wintered at Thanet. The men of Kent promised to pay them off, but the Viking host went inland and attacked the eastern part of Kent anyway. By the end of the summer, more vikings were to arrive in England, this time led by royal princes determined to do more than hit and run.

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle said that these Danes took winter quarters in East Anglia:

"And the same year a great raiding army came to the land of the English and took winter quarters in East Anglia and were provided with horses there, and they made peace with them".

According to Aethelweard writing 100 years later, the Danish leader was Igwar or Ivar, one of the sons of Ragnar Lothbrok. Ragnar Lothbrok or Lodbrok, (Leather Britches), was the most famous viking of his day. He had two sons involved in these first raids. One was called Ubba, and the other was known as Ivar the Boneless. "Boneless" probably refers to the snake, a creature thought to be full of cunning and fearless in battle.

This first attack may have taken place at Harwich, and the area around was possibly held by the Danish army for their winter stronghold, both for ships and men. The name Harwich itself could derive from Here Wic, or Army Port. If Dommoc was located, not at Dunwich, but at Walton Castle, it seems likely that this was the city or civitas first burnt down by the vikings in this attack as described by Abbo of Fleury.

The chronicle implies that King Edmund now paid them off in money, horses and supplies to keep the peace in East Anglia, and prevent further destruction.

Rather than return home with Edmund's payoff, as they had done in the past, the Danes stayed put and would proceed to move against other parts of Britain.

|

|

866

|

Having spent 865/866 in East Anglia, the viking force marched north from East Anglia, took York and thus conquered Northumbria. Meanwhile, their fleet sailed up the coast. The brilliant cultural life of the north, the schools, libraries, churches and minsters were all destroyed.

"An immense slaughter was made of the Northumbrians there".

|

|

867

|

After over-wintering at York, the Vikings moved on Nottingham and the Kingdom of Mercia.

|

|

868

|

Following Danish attacks in the midlands, the Mercians sued for surrender. The Danes went back to York for the winter, and now they would head back to East Anglia.

|

|

Death of Edmund

by Sybil Andrews

|

|

869

|

From York the Great Army of the Danes marched back into East Anglia, but this time they attacked Thetford. Thetford stood on the Icknield Way, at an important crossing point of the Rivers Little Ouse and Thet. The town could be reached not only by the army on horseback but, most importantly, their ships could reach Thetford by sailing into the Wash and then following the rivers through the Fens.

The Chronicle reads as if the Danes had already taken Thetford, intending to settle there for the Winter, when they were attacked by King Edmund, and his Anglo-Saxon fyrd, or army, in late November.

If King Edmund had indeed paid off the Danes to avoid war in 865, we do not know why the same thing was not attempted in 869. Perhaps the Danes now felt strong enough to take him on, or perhaps he had now resolved to resist them. He may have been given no choice, for as we have seen in Kent in 865, one band of Vikings would happily take your money, and then another band might attack you anyway.

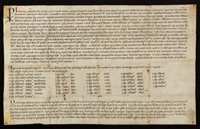

"The Danish host rode across Mercia into East Anglia and took winter quarters in Thetford and in the same year King Edmund fought against them and the Danes had the victory. And they slew the king and overran the entire kingdom". That description came from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, version A, written between 877 and 899, and is the first record of the death of King Edmund, later to be called St Edmund, King and Martyr. A note to the Canterbury Version F of the Chronicles, adds that the Danish head men who slew the King were Ingware (Ivar the Boneless) and Ubba. Version E, copied at Peterborough in 1103 also added that they destroyed, or did for, (fordiden) all the monasteries to which they came, one of which was Peterborough itself.

" The Danish took the victory and killed the king and conquered all that land, and did for all the monasteries to which they came. At the same time they came to Medeshamstede (Peterborough) : burned and demolished, killed abbot and monks, and all that they found there, brought it about so that what was earlier very rich was as it were nothing."

Asser's 'Life of King Alfred' also recorded that King Edmund died in battle, as follows:

"In the year of our Lord's incarnation 870, which was the twenty- second of king Alfred's life, the above-named army of pagans, passed through Mercia into East-Anglia, and wintered at Thetford.

In the same year Edmund, king of the East-Angles, fought most fiercely against them; but, lamentable to say, the pagans triumphed, Edmund was slain in the battle, and the enemy reduced all that country to subjection."

The Danes also attacked Crowland Abbey in the Fens, and burned it down. Other monasteries assumed to have been destroyed around this time include Beodericsworth at Bury St Edmunds, Ely and Soham. Iken, Brandon and Burrow Hill were deserted, and may well have already been destroyed in the earliest attacks. Dommoc disappeared so completely that we are still debating its exact location.

This destruction of monasteries would be very significant because it implies a wholesale destruction of written records and literature in East Anglia, as well as the looting of the valuable trappings of the churches, together with their physical destruction. Steven Plunkett wrote that "The impact of the ninth-century Viking conquest of East Anglia was not superficial: in many ways it was cataclysmic."

|

|

St Edmund |

|

blank |

Later stories were to tell how Edmund was captured in battle, and was offered his life to share his kingdom and renounce his Christian faith. This he refused to do and was shot with arrows and his head was cut off and thrown away. Within a generation Edmund would become accepted as a Christian saint. After the foundation of his abbey at Bury St Edmunds, for some five centuries Edmund was to become not only the patron-saint of East Anglia but also the patron-saint of all England. He is, of course remembered nationally to this day. This icon is a modern commission for the Orthodox Church of St John in Felixstowe.

The death of King Edmund is attributed to November 20th, and this remained his saint's day throughout the monastic period. The stories surrounding Edmund grew more detailed over time, and it is interesting to track the development of the legend.

The growth of the legend of St Edmund is described fully elsewhere in these pages, and can be seen by clicking here:

The Legend of St Edmund. According to Abbo of Fleury, writing in 985, the death of St Edmund occurred at Haegelisdun Wood. According to Herman of Bury, writing in 1095, the saint was then buried nearby at Sutton. Aeldorman Aethelweard, writing at the end of the 10th century said "and his body lies entombed in the place which is called Beadoriceswyrthe".

Some modern writers now support the ideas of Dr Stanley West that the location of Edmund's death was at Bradfield St George, rather than at Hoxne, which had been the claim of the medieval bishops after 1101. Dr West has noted that there still survives an old field name Hellesden, close to a Sutton Hall six miles south of Bury St Edmunds. Two miles north are Kingshall Farm, Kingshall Street and Kingshall Green. It seems likely that St Edmund's death would not have been far from his eventual resting place.

Up to this time there had been a single kingdom of East Anglia, consisting chiefly of today's Norfolk and Suffolk. Its land frontiers were defence works on the Icknield Way facing southwest and joining up two natural boundaries. The Devil's Dyke ran 7½ miles from Reach on the edge of the

marshy Fens to the dense forests still remaining at Stetchworth in the east.

The town of Thetford seems to have been attractive to these invaders as a base in East Anglia. They could bring their longboats up the Wash and follow rivers into the Little Ouse, and on to Thetford. Thetford also had ancient iron age earthworks which could be pressed into service as a camp and horse stockade. Thetford was certainly revived in importance from these beginnings as a Danish winter stronghold. For the next fifty years, East Anglia was under viking control.

The fate of the old monastic foundation at Beodericsworth, (Bury St Edmunds), is not known, and although the Chronicle says that they overran the whole kingdom, there does not seem to be any archaeological evidence yet found of any wholesale destruction by them.

At this time there were a few settlements scattered around Haverhill and we know nothing about their fate under the Vikings. These towns, including Sudbury, had prospered as border towns with Essex in the first decade of Edmund's reign, when East Anglia was at peace with Mercia and Wessex.

|

|

870

|

The Danes now moved against King Aethelred of Wessex and Alfred his brother. Battles took place at Englefield, ten miles west of Reading, at Reading itself and at Ashdown, Basing and Merton. The slaughter was great on both sides, enough to make Aethelwerd comment "that neither before nor after has such a slaughter been heard of since the race of Saxons won Britain in war". King Aethelred died after Easter and was succeeded by his brother, Alfred.

Ealdorman Aethelweard wrote his Chronicle towards the end of the 10th century.

|

|

871

|

King Alfred the Great became King of Wessex and the English until 899. He was a man of letters, so learning and history were important to him, but he was also a very practical man and a warrior. His chief pre-occupation was to ward off the Danish invasions and at first, things were at a very low ebb, and a very large payment of Danegeld was made to keep them out of Wessex.

|

|

873

|

The Danish host continued to harry the country. They now attacked Mercia, and finished off that Kingdom at the battle of Repton. The Danes then proceded to divide up Mercia, and reshape it as a Viking country.

|

|

875

|

With the increasing number of Danish attacks on the coast, the monastery at Lindisfarne was closed, and the monks moved to the mainland. They took with them treasures like the Lindisfarne Gospels, which were written in the period from 698 to 721. In 883 they settled at Chester Le Street, and in 995 they would finally move to Durham. Despite the assaults of Danish raiding parties the monks had saved some of their best books from destruction.

|

|

876

|

After 871, part of the Viking army settled at York and took to farming. Godrum led another part to Cambridge and in 876 they launched another assault on Wessex. They lost 5,000 men at sea, and were forced to retreat.

|

|

878

|

On the feast of Twelfthnight the Vikings surprised Alfred's army at Chippenham.

Much of Wessex was taken by the Danish and their territory was expanded to its greatest ever extent. Alfred even took refuge at Athelney in Somerset, later founding a monastery there in gratitude. By May, Alfred rallied the army and won a decisive battle over King Guthrum, or Godram, at Edington near the Bristol Channel.

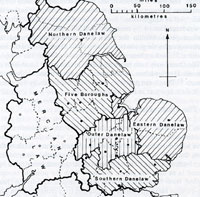

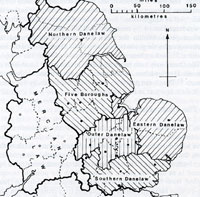

The Peace of Wedmore was made following Alfred's victory at Edington, 15 miles from Chippenham. Under the Treaty the borders of Danish rule were rolled back and established east of Watling Street, along a line from London to Chester. Essex was ceded to the Danes.

The powerful kingdom of Mercia, which had dominated the country on and off for two centuries, was now divided down the middle. Mercia as a power was now finished. It would be Alfred and Wessex which would eventually rise to prominence henceforth. Godrum converted to Christianity and changed his name to Athelstan, his new Christian name. He also agreed to pull his army back into East Anglia. Various ranks of Danish and Saxon citizens and their values were set out in this Peace, and the country was now officially partitioned. The Danish held area was to become called the Danelaw.

As Athelstan, Godrum would start to issue coins in his new name, based upon the coinage of Alfred. For a viking, this was an adoption of English ways, as the traditional viking medium of exchange had always been hack-silver, for exchange by weight.

|

|

The Danelaw |

|

879

|

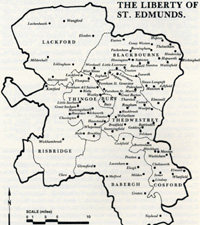

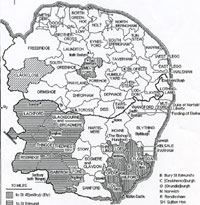

Danish settlement began in earnest following the peace treaty which had given them control over the North and East of England. Because Danish law was applied in these areas they were known as the Danelaw. East Anglia became the Eastern Danelaw, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded the Danish settlement there:

"Here the raiding army went from Cirencester into East Anglia, and settled that land and divided it up".

In many ways the Danelaw, including East Anglia, now became like a Danish province. Old allegiances to local lords were weakened. Before the Danes, land could only be transferred by the King's charter. Viking law allowed it to be bought and sold in front of witnesses, at least in the chief towns of Cambridge, Thetford, Ipswich and Norwich. Streets like Colgate and Fishergate in Norwich took their names from the Danish 'gata', meaning street. York became a Viking capital, and its well known Coppergate derives from this time.

The Suffolk town of Beccles is particularly well endowed with 'gate' street names. These include Ballygate, Becclesgate, Blyburgate, Hungate, Ingate, Newgate, Northgate, Saltgate, Sheepgate and Smallgate.

The Hundred, hide, and virgate of the English south and west become the Wapentake, carucate and bovate of the Danelaw to the north and east. In East Anglia the only Scandinavian name to be widely adopted was apparently the carucate, as the word Hundred continued in use. The Hundreds of northern Britain, north of the Wash, all became called Wapentakes.

|

|

Thor's Hammer pendant |

|

blank |

This pendant of Thor's Hammer was a widely worn protective symbol by Viking invaders. It was found at South Lopham, but examples might be found all over areas where the Viking Army or Viking settlers may have camped. It is a typical "viking object".

'Viking' objects are increasingly found at Ipswich from this period through to the early 10th Century. Markets were known to exist at Ipswich, Bury St Edmunds and Dunwich. By 1086, the list was joined by Haverhill, Clare, Beccles, Blythburgh, Clare, Eye, Hoxne and Thorney at Stowmarket.

However, outside the townships the Danes do not seem to have had a great impact on East Anglian place names. Only in the areas of Flegg, Blofield and Lothingland in the Broadlands area are there any number of the characteristic Viking names like Hemsby and Filby, with the 'by' ending. More places seem to end in 'thorpe', however. Guthrum or Godrum, or Athelstan as he now was, seems to have settled into East Anglia, into the existing hundreds, with his followers, without it would seem, too much disruption. Perhaps they were quite like the Angles who were already there, and fitted in easily, or perhaps they liked the wooded river valleys where the existing people did not care to live. Guthrum had adopted Christianity and was regarded as King Alfred's godson, and no doubt this gave him some legitimacy with the English.

One imposition of Guthrum on East Anglia seems to be that the Bishoprics and their sees were abolished or set aside for next half century at least.

The administrative unit known as the "hundred" has an unknown origin. However, it is likely that it was brought into being by the Anglo Saxon kings. They survived through the period of Danish supremacy, even if they were renamed as Wapentakes, and seem to predate the later invention of the "shires". Later the hundreds would have their own courts, often held at a ford, or at a prominent hill or barrow, also known at the time as a hoe. Examples are the Thingoe and Thedwastre hundreds in West Suffolk. The seat of the Thingoe Hundred has been long considered to be in the area of today's Northgate Avenue in Bury.

|

|

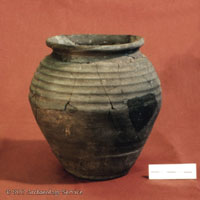

Ipswich Thetford-Type ware

Ipswich Thetford-Type ware |

|

880

|

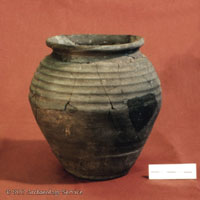

Ipswich ware has been thought to have been produced from about 650 to 850. However, in The Ipswich Ware Project Paul Blinkhorn concluded that this range was more likely to be from 720 to 850. Nevertheless, by the mid to late 9th century, a new type of pottery was emerging which has been called Thetford Ware. On the website WWW.spoilheap.co.uk, by Sue Anderson, there is a is a good description and explanation, as follows:

"Thetford-type ware is so-called because kilns for the manufacture of this Late Saxon wheelmade pottery were first uncovered in Thetford. However, it is likely that the ware developed in Ipswich, where kilns have also been excavated, and was first made by Ipswich ware potters in the late 9th century. It is a medium sandy greyware, although fine and coarse fabrics are also known.

The main forms are plain jars with everted rims, but other forms included spouted bowls and pitchers, large strapped storage jars, handled jars and lamps.

This cooking pot is typical of the Ipswich variety of Thetford-type ware. It is in a relatively fine blue-grey sandy fabric and is girth-grooved. Other forms of decoration included bands of diamond rouletting (produced using a tool similar to a pastry wheel), applied thumbed strips, and occasionally incised wavy lines.

Thetford-type ware was produced in several areas. The main kilns were in urban centres such as Ipswich, Thetford and Norwich. It is possible that pots of this type were also being made in Sudbury and possibly Bury St. Edmunds. Rural production sites have been identified at Grimston and Langhale in Norfolk, but there were probably others."

Thetford type ware would continue to be produced into the mid 12th century.

|

|

880's

|

Despite the Peace of Wedmore, new Viking bands continued attacks on Wessex, although they also attacked continental Europe. The East Anglian Danes also used the Danelaw as a base from which to harry the west country.

They set up the five fortified boroughs of Leicester, Nottingham, Derby, Lincoln and Stamford to control and defend the Danelaw. York was the capital, well north of the treaty borders.

|

|

884

|

The Danes continued to harry Wessex at Rochester. The East Anglian Danes apparently joined in, and were attacked by Alfred. "And the same year King Alfred sent a raiding ship army into East Anglia. Immediately they came to the mouth of the Stour, then they met 16 ships of vikings and fought against them, and got at all the ships and killed the men".

|

|

885

|

By now the Danes under Guthrum had largely converted to Christianity, and within only twenty years of Edmund's death, they themselves were issueing coinage in his memory.

|

|

Memorial Penny from Thetford |

|

blank |

Viking coinage of Danish East Anglia was issued from 885 to 915. St Edmund memorial coinage was produced, as was coinage in memory of St Martin of Lincoln.

The coin shown here was found at Thetford in 2002. J North in his English Hammered Coinage describes this as possibly dating to the later period of Viking occupation of about 905 to 910, because the legend or lettering is "blundered", that is to say that it looks plausible, but makes no sense that we can discern today.

Another memorial coin, with a better legend in memory of Edmund, was copied for the 1907 Bury Pageant medallion. The moneyer was OTBERT, but the location of the mint is unknown.

It is entirely possible that the mint was in Thetford, a major town at this time. Possibly it was as big as, or bigger than, either Norwich or Ipswich in the late 9th Century.

Meanwhile Beodricsworth, the settlement to become Bury St Edmunds eventually, was probably a small community, possibly living on its memories of being a royal vill from the time of Sigbert, but now of no real importance.

|

|

886

|

"King Alfred occupied London fort and all the English race turned to him, except what was in captivity to Danish men".

|

|

The Alfred Jewel

The Alfred Jewel |

|

890

|

The Dane Guthrum, who had converted to Christianity and settled with his band in East Anglia, died in 890, and was buried at Hadleigh. The Stour valley was, perhaps, where he had settled. He had a Christian burial, possibly at the ancient Aldham church.

By 890 King Alfred had held Mercia and Wessex and established a balance of power with the invaders. Alfred now found time to translate Latin texts into English and had these distributed to monasteries throughout his lands. One such text was "Pastoral Care" by Pope Gregory, which laid down the duties of priests to the people. To emphasise the importance of these texts and to encourage them to be read aloud to the monks, King Alfred would send out jewelled pointers or aestels along with the translations. This is believed to be the purpose of the so-called Alfred Jewel, illustrated here. An ivory or bone stylus was thought to be fixed to the bottom of the jewel, but is now lost. The inscription on it may be translated as "Alfred had me made".

None of these texts or artefacts would have penetrated into the Danelaw, where Christianity was becoming more acceptable to the Danes, but there were no functioning Bishoprics or monastic foundations as far as we know. It is generally thought that Sigeberht's monastery at Beodericsworth, or Bury St Edmunds, founded in 635, was defunct during these years.

Coins were minted naming Alfred King of the English, but of course, in practice, this excluded the Danelaw, north and east of a line from London to Chester.

|

|

The Cuerdale Hoard

The Cuerdale Hoard |

|

892

|

Vikings landed in Devon and raided for more than a year. Alfred constructed burhs or defensive strongholds along his borders, following the Danish example. He also designed new ships meant for naval battles.

|

|

893

|

The Danes, including those from East Anglia, continued to attack in the west, at the Severn and north to Chester. The Welsh monk Asser wrote a "Life of King Alfred", in which he refers to the death of King Edmund in battle. John Asser became Bishop of Sherborne in the 890's, and worked for King Alfred in translating latin texts into English. Meanwhile the coinage known as St Edmunds memorial coinage continued to circulate in East Anglia as official Danish currency, testifying to the rapid acceptance of him as a Christian Martyr. His story was becoming more and more well known.

|

|

894

|

The Danes retreated to the East and fortified the area, but various battles continued on the borders of Wessex.

|

|

899

|

King Alfred died and was succeeded by his son Edward the Elder, who set about encroaching on the Danelaw himself.

By about 900 the Danes of East Anglia were becoming fully Christianised and more coinage was circulated which commemorated King Edmund. Perhaps the idea of honouring him as a saint was becoming universally accepted.

However, the Norse settlements in Scotland, Isle of Man and Ireland were now becoming a threat even to the Danelaw.

|

|

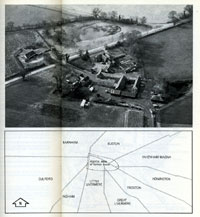

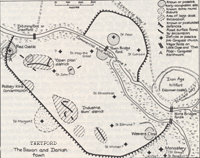

Danish and Saxon Thetford

Danish and Saxon Thetford |

|

904

|

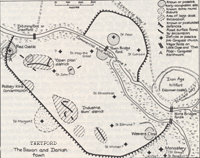

The East Anglian Danes again started to raid into Mercia. King Edward retaliated and attacked between the Devils' Dyke and the Fens.

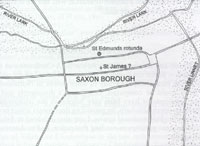

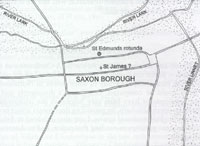

At some point around AD 900, a defensive ditch was erected to protect the fords at Thetford and the growing town. Much of the land enclosed by the ditch was still undeveloped farmland at the time. Alan Crosby's map shows the likely extent of the 20 foot wide ditch and bank enclosure. Crosby recorded that the ditch and bank remained visible up to the 18th century. A section remains today between Red Castle and the London Road. Please note that some features on this map, particularly churches and the monastery, date from well over a century later.

At this time Thetford was a town based around areas to the south of the Rivers Little Ouse and Thet. During the later Norman period the focus would switch to new developments north of these rivers.

|

|

905

|

The peace of Tiddingford was confirmed between King Edward the Elder and the Danes both with the East Anglians and the Northumbrians.

|

|

906

|

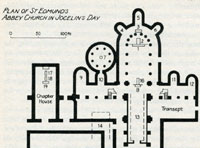

St Edmund's remains were moved to Bedericsworth from their original burial place in a small chapel at Sutton near to the site of his martyrdom. This must have happened with active Danish involvement and support. At Bedericsworth, (Bury St Edmunds) the wooden church of St Mary was enlarged and improved to hold the new shrine for St Edmund.

Back in the days of King Sigbert he had set up a small monastery there, but it seems unlikely that the monastery still remained from 630 as local lay volunteers had to guard the shrine. The acquisition of so notable a relic as a royal saint was to make the small town a place of pilgrimage and recipient of many royal grants for over 500 years.

Tradition was that one Oswen would open the tomb every Holy Week to cut the saint's hair and clip his nails.

|

|

910

|

The English and the Danes fought at Tettenhall.

|

|

912

|

King Edward the Elder, the son of Alfred the Great, took an army to Maldon in Essex and built a stronghold at Witham,

"and a good part of the people who were earlier under the control of the Danish men submitted to him". Fortifications were also built elsewhere, and it is possible that Bedericsworth was made into a fortified burh at this time, although this privilege is also attributed to King Cnut over a century later than this. Bungay and Sudbury may have been likewise fortified. At places like Thetford and Cambridge, where the Danes already had forts, Edward may have built his own burhs or forts to face them.

In Yates' Antiquities of 1805, he quotes various monastic papers as recording that Edward the Elder marched an army into East Anglia to repress the Danes. Having ravaged the country he retreated, but his Kentish men stayed behind at Bury, desirous of more plunder. They were then attacked by an alliance of Danes and the Saxon Ethelwald who wanted to contend for Edward's crown. In the battle, Ethelwald died, but the Kentish men were routed by the Danes.

The exact years in which this took place is open to doubt. One version of the Anglo - Saxon Chronicle gives 912 AD, but others read it as 920, but the most recent interpretation settles it at 917.

|

|

916

|

Edward the Elder set up several more fortified burhs, including Maldon in 916.

|

|

917

|

This was a turbulent year. Danish controlled Colchester was overcome by the army of Edward the Elder and many of its inhabitants killed. Edward was making it his mission to recover the Danelaw from the Danes, ignoring the peace treaty set up by his father, King Alfred the Great. Hundreds were killed in a siege at Maldon when the vikings fought back. King Edward the Elder then repaired and restored Colchester as part of the peace now agreed. The Danes decided to avoid a full scale invasion from Edward and his Wessex men. The chronicles say that many people submitted to him from both East Anglia and Essex which had been under Danish rule. The Danish controlled force from Cambridge also accepted Edward as Lord and Protector.

This peace treaty is interesting in that the Danes of East Anglia do not agree to surrender. They agree to "annesse", or oneness. A union of the two peoples is agreed. This allows East Anglian Danes to retain their lands and their laws, whereas the Cambridge and Essex Danes have to submit. Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire had already capitulated in 912.

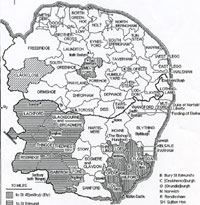

Because of this peace treaty, it has been suggested that the Shires of Norfolk and Suffolk were imposed on East Anglia at this time. However, Dr Lucy Marten argues that this did not happen at this time, because of the particular type of treaty agreed. She argues that East Anglia continued as one entity until the time of King Cnut. Peter Warner in "The Origins of Suffolk", also argues that the county boundaries did not exist at this time, but he suggested that they did not come into being until the time of the Norman Conquest.

Please note that the date of this attack by Edward the Elder has been unclear to many writers, and it has been described as happening earlier, in 912, or even as late as 920. Nevertheless, by this time Edward seems to have broken up Mercia, his rival kingdom, into shires such as Cambridgeshire, Warwickshire and Staffordshire to weaken it as one unit. A Reeve or Sheriff was set up over each shire. Because of the arrangement now agreed, it seems that East Anglia was not similarly broken into Norfolk and Suffolk at this time.

Edward has been said to have set up the system of hundreds, as sub divisions of the shires, for the purposes of administration and taxation. However, it is more probable that these were older, dating from the days of Anglo Saxon control, and that the Mercian shires were made by grouping hundreds together. No doubt, where it suited Edward for political reasons, he would carve up the existing hundreds to make his shires along new boundaries which he specified.

|

|

920

|

By 920 the viking coinage seems to abruptly disappear from the East Anglian scene. A hoard of coins deposited at Brantham in about 920

contained only coins of Edward the Elder. There were no St Edmund memorial pennies, and no viking coins at all. This seems to indicate that Edward had held a massive re-coinage which resulted in all earlier coins being exchanged at his mints to be melted down and re-issued in his name. They were also issued at the new higher weight standard which had hitherto not been adopted within the Eastern Danelaw.

This reflects the fact that East Anglia agreed to "oneness" with Edward the Elder, and the Scandinavians gave up the right to produce their own locally designed coins.

|

|

923

|

York was taken by the Norsemen under Raegnald and held by Norse Kings until Eric Bloodaxe was killed in 954.

|

|

924

|

Despite Norse success at York, by the end of his reign Edward the Elder had pushed the Danes northward into Northumbria. When Edward the Elder died in 924, he was succeeded by Aethelstan who quickly took over Northumbria and Cornwall.

|

|

925

|

According to Yates' Antiquities, monastic papers recorded that in 925 the ecclesistical votaries of St Edmund were incorporated into a college of Priests, either by King Aethelstan, or by Bederic, under royal protection. Bederic was, or had been, the local chief lord, and he or his descendants may have supported the new shrine by giving it land for the clergy to live off. This story is merely reporting a more formal arrangement being put in place to maintain the shrine of St Edmund.

|

|

927

|

King Aethelstan invaded Northumbria and took York, expelling the vikings, including kinsmen of Anlaf Guthfrithson, the king of Ireland.

|

|

932

|

The kings of Wessex tended to rule their dominions by way of Eldermen, or Ealdormen. From 932 East Anglia was run by Elderman Athelstan, who became so respected and powerful in East Anglia that he gained the popular name of Athelstan Half-King. Perhaps this helped to distinguish him from Aethelstan, King of Wessex.

This title supports the view of Dr Lucy Marten that East Anglia was still un-shired at this time. The old kingdom of East Anglia was still in one piece, and so Athelstan ruled the old kingdom, but perhaps because he owed allegiance to King Athelstan of Wessex, he was known as half-king.

|

|

New site of Brunnanburh

|

|

937

|

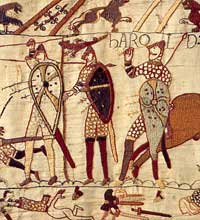

In retaliation for Aethelstan's capture of Northumbria and York in 927, the Irish King Anlaf Guthfrithson, Owen king of Strathclyde and King Constantine of Scotland joined forces to invade England in the summer of 937, with a massive fleet of ships. Aethelstan advanced out of Mercia to meet the invasion, and this occurred at the Battle of Brunnanburh.

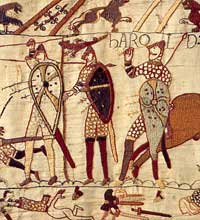

The chronicles merely report that King Aethelstan won a major victory at Brunnanburh and the Northmen's lord was put to flight back to Dublin. This battle remains rather obscure to us today. We do not know where it took place but it is thought to have been the bloodiest and most important battle on British soil until the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The poem Battle of Brunanburh recounted that there were "never yet as many people killed before this with sword's edge ... since from the east Angles and Saxons came up over the broad sea".

The anglo-saxons under King Aethelstan, grandson of Alfred the Great, had to fight the combined forces of Vikings, Scots and Northumbrians. Had Aethelstan lost the battle it could have meant the end of Anglo-Saxon England.

More than 30 places have been suggested as the site of Brunanburgh, one of the most popular being at Bromborough on the Wirral at Merseyside. Professor Michael Wood suggested in 2017 that it was far more likely to have been fought along today's A1, always the main route from Viking York to Mercia, Wessex and the English heartlands. He prefers a site at Robin Hood's well, near Burgh Wallis, a village seven miles north of Doncaster.

|

|

940

|

King Edmund (NB not our St Edmund) succeeded Athelstan and continued the war with the Danes. Edmund was grandson of King Alfred the Great and ruled Wessex from 939 to 946. Because he was named after St Edmund he took a great interest in his shrine at Bedericsworth.

Edmund was also interested in the church in general and wanted to help the monasteries in any way he could.

|

|

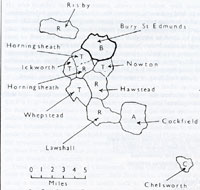

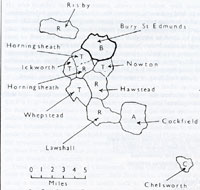

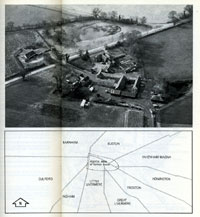

Banleuca Boundaries by C R Hart

|

|

945

|

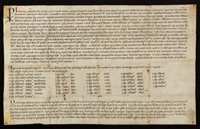

According to an Anglo-Saxon Charter, in 945 King Edmund gave up his royal rights to taxes and all feudal dues and fees in the area of Bury St Edmunds for about one mile around St Edmund's shrine. M. D. Lobel was not the first writer to consider that this charter was spurious, invented by the monks at a later date to bolster their claims. Their reason for doing this would be that this was the first charter to grant many of the privileges claimed by the monastery. As such, its existence needed to be established, because later grants and charters tended to confirm existing rights, while in some cases, extending them.

There is no original of this document as it had been replaced by fresh versions. In later years it was normal practice for well worn and faded old records to be copied in the monastic scriptoria for everday use. So we have only a few of these later copies to consult, and they are not all consistent.

Since Lobel's day there has been much research into these early charters, and in 1968 P H Sawyer produced a catalogue called "Anglo-Saxon Charters: an Annotated List and Bibliography". This replaced earlier lists by J M Kemble, published in 1839-1848, and W Birch in 1885 to 1893. This charter of 945 is now catalogued as S 507, and further details can be seen by clicking on that reference.

Dr Cyril Hart largely accepted the authenticity of this charter and other recent research has described the content of this charter as "worthy of favourable reconsideration."

|

|

The charter exemptions by Yates |

|

blank |

Cyril Hart summarised the charter as, "a statement that the land surrounding the monastery is to be free of all tribute, such payment being rendered solely to the monastery. This appears to represent exemption from the three common dues - a rare privilege - together with exemption from from the payment of taxes into the royal fisc; when a national tax is levied (based on the hidage) the inhabitants are to pay their levy to the monastery, and not to the king."

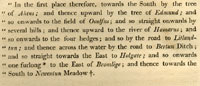

In 1805, the Reverend Richard Yates provided his own translation of this charter, which may be read by clicking on the thumbnail shown adjacent to this paragraph. According to Yates, the monks stated that this was their first charter, and that, "This has the priority of all our charters." This translation does not refer solely to the freedom from taxation, but actually appears to include a gift of the land itself. If so, we must assume that the land was in the king's ownership to enable such a gift to be made. Yates's translation for this section is as follows:

".....I freely give to the monastery situated in the place called Bedericheswyrthe, where rests the body of St Edmund, King and Martyr, the land around the same place, in such a manner that the family of that monastery may possess it and eternally continue to do so; and, by the same authority, transmit it to their posterity......free from every worldly obstacle......and let it not pay any tax except to the use of the family of that church......"

Exactly what happened to Bederic's own rights as the local lord, at this time is not known. Although the documents do not seem to imply that he, (or his rightful successors), lost any of their old rights in 945, perhaps he had already lost his lands. Thus Bederic may, or may not, have continued to receive his own local dues. These may have included Landmol, a rent on farmland in the town fields, which lay outside the town boundary. Jocelin tells us that by his time, from every acre of the nine hundred that had been Bederic's, the payment was two pence. By the time of Jocelin of Brackland, in the late 12th century, this rent was collected by the reeve and paid to the sacrist.

Bederic himself was either paying some of this cash over to the Earl, who had the rights in East Anglia, or he was providing other duties and fees to him as landlord in chief. We do not know how the old Saxon system of dues had been altered by Viking rule.

Jocelin also believed that, "when the town was made free, [presumably 945] the service owed for these lands was divided into two, in such a way that the sacrist or the reeve took a levy at the rate of 2d per acre, and the cellarer had ploughing and other services." In fact, we must treat this assertion with caution, as it is doubtful whether these posts existed at this time in this pre-Benedictine community. However, Jocelin was sure that this arrangement was very old.

Jocelin also reported that by his time, (c1198) the Cellarer of the Abbey held a messuage and barns near Scurun's Well, "which had been the manor house of Beodric, lord of this town in ancient days, after whom the town used to be called Beodricsworth. His fields are now in the demesne of the cellarer, and what is now called averland was the land of his peasants. The total estate which was held by him and his men consisted of 900 acres, and these lands are still the town fields." According to Antonia Gransden the cellarer's manor was known as the grange of St Edmund, or Eastgate Barns. The Scurun's Well messuage and barns therefore seems to be identified with Eastgate Barns, sometimes referred to as Holderness barns along Holderness Lane, off Eastgate Street. On the OS map for 1955 it is named as Grange Farm.

Moving on now to the area which was included within this grant of privileges, this was described within the otherwise latin charter as a perambulation in Old English, which reinforced Hart's view that this part was, indeed, genuine.

The part of the charter which deals with the boundaries of the granted area is very confusing to modern eyes. We cannot recognise many of the landmarks. In S 507 the text goes as follows:

"This sindon tha land gemere the Eadmund king gebocade in to sancte Eadmunde . thonne is thær ærest suth be eahta treowen . 7 thonne up be Alhmundes treowen . 7 swa forth to Osulfes lea . 7 swa forth on gerihte be manige hyllan . 7 thonnen up Hamarlunda . 7 swa forth æfter than we se Lytlantune . 7 thonen ofer tha ea æfter than wege to Bertenedene . 7 swa on gerichte east to Holegate . 7 swa forth an furlang be easten Bromleage 7 thonan suth to niwantune meaduwe."

This list of landmarks may be translated as follows:

- First south by the Eight Trees

- Then up by Ahlmunds trees

- So forth to Osulf's meadow

- So forth on the right by many hills

- Then up Hamarlunde

- To four mounds (hogas-after Hart and not in S507 version)

- So forth after we see Little Town

- Then over the running water

- After then the Way to Berten or Barton Valley

- So on right east to Hole Gate

- So forth one furlong by Eastern Bromleage

- Then south to Nowton Meadow

Dr Cyril Hart has produced the attached map which plots his interpretations of these landmarks. Such a boundary description is known as a "perambulation", and was the normal method of describing a location at this time. Oliver Rackham has pointed out how often major trees or woodlands were regarded as permanent landmarks in these perambulations. Incidentally Dr Hart has also pointed out that this charter contains the earliest known reference to a unit of length called a furlong. A furlong was later fixed as 220 yards, or about 201 metres, but how precisely this distance was measured or understood at the time is unclear. Later there would be 8 furlongs to a mile. The word was said to derive from the words Furrow Long.

|

|

The charter town boundaries in Yates |

|

blank |

In Richard Yates "Antiquities of Bury Abbey" of 1805, Yates gives a different latin text, and provides his own English translation, which is shown here. However, once again, there is an inconsistency over dates. In the monastic copy of the decree cited by Yates, and pointed out by him, the date of the copy charter he saw was referred to as 945 at its start, and 942 at its end. The ending of the copy denoted as Sawyer S507 gives the date as 945, as follows:

"Acta est hæc præfata donatio anno ab incarnatione domini nostri Jhesu Christi . DCCCC . XLV . Indictione . III . "

The record states that King Edmund gave these rights to the collegiate church (also called the convent) of St Edmund. It would appear that by now, the lay volunteers who had first tended the shrine since 906, had been incorporated into a college, or body, of priests. King Edmund was the son of Edward the Elder and granted the lands round Beodricsworth to the 'Familie monasterii,' or family of the monastery, as it is termed in one charter quoted by Arnold in Memorials of the Abbey of St Edmund. (See charter S 507,). At that time the household or college of clerks, to whom the duty of guarding the shrine was assigned, consisted of six persons, four priests and two deacons, according to Herman in 1095. They probably also supported their wives and families.

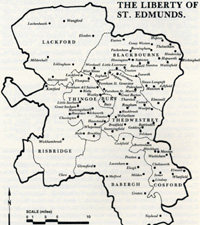

This area of land was later to become known as the Banleuca and its grant indicates the important status of the shrine of St Edmund and the growing importance of its monastery. The income from the Banleuca belonged, therefore, to the college of priests as a whole, and did not belong to the Abbot alone when in later years, this was to become an issue. Most of this area was farmland at this time, with only small settlements around the farms, and Bedericsworth was just a growing village around the shrine. In later years the boundaries of the banleuca were to be marked by four stone crosses on the main roads into town. The map shown here displays the banleuca and parish boundaries by the 1990's, overlaid on features that would have existed in the 15th century, but are now gone. This grant of land by King Edmund effectively defined the administrative boundaries of Bury St Edmunds right up until 1934 when parts of Westley and Fornham were added to the town to the north west. This additional land is also outlined on this map.

One significant factor in this story may be that it was in 945 that King Edmund married the Lady Aethelflaed of Damerham. Damerham is in Wiltshire, but Aethelflaed was the daughter of Aelfgar, who had just become the Ealdorman of Essex. Aelfgar held estates in Essex, but also had lands in the county that we know today as Suffolk. In 945, however, this name did not exist. It was part of East Anglia. Nevertheless, suddenly the King has now got a family interest in some land in East Anglia, and perhaps prompted by Aethelflaed, he made this gift to St Edmund. It was not a large area by the standards of royal monastic endowments of the period, but maybe that was all there was to give, and maybe the shrine had few needs at the time. This was a small part of the slow integration of East Anglia into the control of the Kings of Wessex and England.

Another significant factor surrounding this arrangement is the effect it must have had upon other local taxation arrangements. By 1086 we know that Sudbury was added to the Hundred of Thingoe. It seems likely that this would have taken place to compensate Thingoe Hundred for the loss of the tax revenues from the Banleuca of Bury, and thus it is likely to have been undertaken at the same time that Bury was exempted from the tax. This puts the arrangement in 945, and also leaves us with the conclusion that the Hundredal system itself was established by this time. If we accept that East Anglia was not divided into Norfolk and Suffolk until the time of Canute, c. 1021, then it follows that the Hundredal system pre-dates the introduction of Shire Counties.

Not only did King Edmund give the monastery a permanent independent income from the Banleuca, he was also said to have given it the manor of Fornham Parva, its first landed property outside the town precincts. Fornham Parva is considered by Dr Hart to be the "Little town", of the charter perambulation, and is now called Fornham St Martin.

|

|

946

|

Eadred became King of Wessex following Edmund's death. There were no Bishops of East Anglia at this time, but it appears that the Bishop of London had a manor at Hoxne, from which he may have exercised some degree of church authority. Bishop Theodred seems to have been Bishop of London around 938 to 941.

|

|

947

|

During the 940's the area around Rendlesham, from the River Orwell to the Alde, was administered as one province by a Danish earl. The area was then known as the Wick Law, or Wicklaw, or Uicchelaue, but was probably an old administrative unit dating back to Raedwald and the Wuffing Kings of the early 7th century. Its base was at Sudbourne, near Iken, at this time.

|

|

948

|

In the period from 946 to 951, Aelfgar, the Ealdorman of Essex, made his will. This will is catalogued by Professor Sawyer as S 1483.

Aelfgar not only held estates in Essex, but much land in today's Suffolk, south and west of Bury.

It is interesting to see from this will, that the right to make a will was not easily available to everybody. Aelfgar, despite his position, had to earn the right to make his will, as follows:

"And Bishop Theodred and the Ealdorman Eadric told me, when I gave to my lord the sword which King Edmund gave to me, which was worth a hundred and twenty mancuses of gold and had four pounds of silver on the sheath, that I might have the right to make my will; and God is my witness that I have never done wrong against my lord that I may not have this right."

Aelfgar seems to have become an Ealdorman around 944, and his daughter Aethelflaed became the second wife of King Edmund in or about the same year. By this time she was, of course,a widow, King Edmund having died in 946. In his will, Aelfgar left his estates at Cockfield, Ditton and Lavenham to Aethelflaed. However, after her death, he willed that Cockfield should go to St Edmund's foundation at Bedericesworth, and Ditton should pass to "whatever holy foundation seems to her most advisable."

The sentence in Old English referring to Bedericesworth is as follows:

"And þanne ouer vre aldre day ic an þat lond at Cokefeld into Beodricheswrthe to seynt Eadmundes stowe."

Aethelflaed had a sister called Aelfflaed, and in the years between 1000 and 1002, she also left an estate at Cockfield to St Edmund's. It is not clear if this is the same land or another parcel of land at Cockfield. If it is the same land, then it shows that Aelfgar's will was slightly amended in later years to allow both sisters the benefit of the income before it passed into the hands of the monastery of St Edmund.

Aelfgar's will also said the should Aethelflaed produce a son, then he would inherit Lavenham after her death. If not, Lavenham would pass to a religious house at Stoke, presumably Stoke by Nayland. Stoke was also to inherit woodland at Ashfield from Aelfgar.

Aelfgar's connection with Stoke by Nayland is explained in Aelfflaed's later will. She asks in her will, Reference S 1486 of 1000 x 1002, that "my Lord protect the holy foundation at Stoke, in which my ancestors lay buried."

Another local bequest in Aelfgar's will was of the estate at Rushbrooke which he left to his mother, and on her death to one Winehelm.

|

|

951

|

In the period between 942 and 951, Bishop Theodred of London made his will. This is recorded as reference S 1526 in the Sawyer catalogue of Anglo-Saxon charters. He left a number of bequests of land to his family and to various churches, including St Paul's in London.

One bequest was "land at Horham, Athelington, (Suffolk), to St Æthelberht's church at Hoxne". Hoxne was the Bishop's episcopal demesne, or official church seat, and the church there was still dedicated to St Aethelbert. It was not until the 11th century that the dedication was changed to St Edmund, perhaps indicating that Edmund was not thought to be connected to Hoxne at this time.

Another bequest of importance to the monastery at Bury was as follows: "land at Nowton, Horningsheath, Ickworth and Whepstead, to St Edmund's church." Theodred does not need to mention the location of St Edmund's church, but records that the bequest is for the sake of Bishop Theodred's soul.

Another bequest of local land was "land at Barton, Rougham, Pakenham, Suffolk, to his kinsman Osgot, Eadulf's son".

This charter of 942 to 951 is catalogued as S 1526, and the Old English text and other details can be seen by clicking on that reference.

|

|

952

|

King Eadred commanded "that many should be put to death" in Thetford in vengeance for the death of the Abbot there. This was Abbot Eadholm of Canterbury, and why he was in Thetford and why he was killed, we do not know. However, East Anglia did not have its own local bishoprics during this period of Danish rule, and neither did King Eadred seem to have any lands in the area. In his will, Eadred would leave money to Mercia to protect themselves from the Danes, but left nothing to East Anglia, which was much more in the front line than Mercia. So Eadred did not wield the same power and authority in East Anglia as he did elswhere. Perhaps he had sent Abbot Eadholm to establish a new minster under royal control, or to collect taxes for him. Eadholm met deadly resistance, whatever his mission, and the King had to take bloody revenge.

|

|

954

|

The end of Scandinavian domination in Northumbria came when Eadred, King of Wessex defeated Eric Bloodaxe at York in 954. In the 25 years peace that followed there was a cultural and religious revival.

During the 950's it has been written that the Bishop of London inspected the body of St Edmund in his shrine and confirmed that it was incorrupt, and only a thin red crease, like a piece of thread, showed where the head had been severed. Presumably this would have taken place before East Anglia had its own Bishop again.

|

|

955

|

Between 952 and 956 King Eadred set up the new diocese of North Elmham to serve Norfolk and Suffolk. The dioceses of South Elmham and Dommoc had been set up in about 680, but had been defunct since 872, through the period of the Danelaw. So from 955 East Anglia once again had its own Bishop and church hierarchy. The new Bishopric of Elmham covered the areas of the original two dioceses.

The names of the first Bishops of North Elmham have been listed in Wikipaedia as Athulf, (955-962), Alfrid, (962-967) and Theodred II, (967-973).

By the end of 955 King Eadred was dead, and was succeeded by King Eadwig, or Eadwy.

|

|

956

|

The newly crowned English King, Edwy, is recorded as having given the manors of Beccles and Elmswell to the monastery of St Edmund. Registers such as that of Walter de Pynchbeck also state that many of the undocumented possessions of the collegiate church of St Edmund were given in this same period of 952 to 956. The lack of charters and grants from these days was attributed to the confusion of the eviction of the secular priests and their replacement by Benedictines, which would take place in 1020.

Norwich and Thetford had both flourished in this century, expanding beyond their old fortified limits.

|

|

King Edgar's religious reforms

|

|

959

|

Edgar became King of England, following the death of Eadwig or Eadwy, and appointed Dunstan as Archbishop of Canterbury in 961. Dunstan, with St Aetholwold and St Oswald, embarked on a programme of Church expansion and reform based on the new French ideas of monastic life. Dunstan was already committed to the Benedictine way of monastic life, and he would proceed to promote it with Edgar's full approval. The illustration is dated 966, when the New Minster at Winchester was given its reformed Benedictine Charter. The painting represents the brand new Winchester style of illustration.

When Edgar became sole king of England a uniform coinage was instituted throughout the country. A royal portrait was on one side. The reverse had a cross with the name of the mint as well as the moneyer. Under Eadgar most fortified towns of burghal status were allowed a mint. The number of moneyers depended on the size of the town. Thetford was certainly one of those towns allowed to produce coinage. Many of the coins of King Edgar do not include a mint mark. J J North recorded an uncertain mint mark of "THI", which he tentatively attributed to Thetford, with a moneyer called Aelferd.

Bury St Edmunds does not seem to have qualified to have a mint at this time, reflecting its comparative lack of importance as a commercial centre at this time.

King Edgar also recognised some of the old Danish liberties by now well established in East Anglia. This contrasted with the status of Englishmen who were still subject to the king's laws. The relative freedoms thus retained by the Anglo-Danish East Anglians helped to stimulate economic activity and wealth in the region. Some people hated Edgar for this tolerance of 'evil foreign customs'.

Thus, despite East Anglia having nominally been "re-conquered " by the Kings of Wessex, who were now Kings of England, East Anglia remained one unit, not yet divided into Norfolk and Suffolk. Its local government was still run by Aethelstan Half King, and the Witan or council of the richest and noblest local aristocracy.

|

|

960

|

Around this time Aethelstan withdrew to become a monk at Glastonbury. His son Aethelwald now became Ealdorman of East Anglia until 962.

|

|

962

|

In 962 Ealdorman Aethelwald of East Anglia, and son of Aethelstan Half King, died. According to William of Malmsbury, he was killed by King Edgar, in revenge for a deception involving a woman. Aethelwald's brother Aethelwine now became the Ealdorman of East Anglia, a post he would hold until 992.

King Edgar drew up his will, (Sawyer reference S 703), and left 7 hides of land at Chelsworth to Aethelflaed of Damerham. She had been the second wife of King Edmund, and thus was stepmother to Edgar. This land seems to have later passed into the hands of Aethelflaed's sister, Aelfflaed, because Aelfflaed would in turn leave it in her will, dated between 1000 and 1002, to the holy foundation of St Edmund.

These wills are difficult to date, because they are drawn up sometimes well before the author's death, and can only be dated by the witness list attached to them. These lists were drawn up in strict order of precedence, with the most important names at the head of the list. These wills do not actually take effect until the author dies, and this date is often also unclear.

Thus we have the will of Theodred, which follows, drawn up probably before this date, but not put into effect until his demise around this year. This event was recorded by Yates, in his Antiquities of the Abbey, published in 1805.

Theodred the second, the Bishop of Hulm, (which we call Elmham), and London, left to St Edmund's the manors of Nowton, Ickworth, Whepsted, Horringer, and 'other valuable manors in the vicinity of Bury'.

Bishop Theodred also left lands to other monastic foundations. He gave land at Horham and Athelington to St Aethelbert's church at Hoxne for God's Brethren to benefit. We may note at this point that there is no suggestion of any link between St Edmund and Hoxne at this time. St Aethelbert's church at Hoxne would not be re-designated to St Edmund until about 1102.

|

|

966

|

Adulphus, or Athulf, became Bishop of Hulme, (Elmham) after Theodred, and he also bequeathed valuable properties to St Edmund. In his case it was said to be nine manors, the biggest gift so far. Yates also reported that monastic papers claimed that around this time the monastery also received Cockfield and Chelsworth from Ethelfled's will, the daughter of Earl Alfgar. The King's Chancellor Turketell, gave it Culford, part of Palgrave, and other possessions.

|

|

969

|

Ramsey Abbey in Huntingdonshire was founded by Archbishop Oswald, under the lay patronage of Ealdorman Aethelwine of East Anglia. The Ealdorman was responsible for most of its initial endowments from his own possessions. The importance of Ramsey for St Edmundsbury is that the first Life of St Edmund would be written there in 985. That fact is undisputed, but more uncertain is the relationship between Ramsey and the monastic foundation at Bedericsworth. Both Antonia Gransden and Cyril Hart suggest that the clerks at St Edmunds were now placed under the spiritual direction of Ramsey Abbey. Hart also suggests that any such control was extinguished in 1016 at the Battle of Assendun, where Ramsey monks were present on the 'losing' side, and King Cnut then personally took St Edmunds under his wing.

Ramsey was located within Mercia, an area much more amenable to central control than the independent East Anglia, and this period of suggested "control" by Ramsey must still be open to some doubt. Although Aethelwine was Ealdorman of East Anglia, his home was at Upwood, close by Ramsey, and it seems that he also did not get very much involved with issues inside East Anglia.

|

|

King Edgar and Regularis Concordia |

|

970

|

A new set of regulations for monastic life in England, based on Benedictine practice was drawn up by Ethelwold, (later St Ethelwold), the Bishop of Winchester, with the close approval of Dunstan, (later St Dunstan), the Archbishop of Canterbury. It was known as the Regularis Concordia. The Regularis Concordia, organised by King Edgar as an agreement between the king and the monks and nuns of England, required that they simplify their lives, and follow the sixth-century Monastic Rule of St. Benedict from Italy. In return, the monks were under the special care of the king, and nuns under the care of the queen. In addition, the monks and nuns of England, as those who lived the most saintly monastic lives, were required to offer prayers for the King and Queen.

These new rules led to such a well trained body of monks that monastic life remained strong throughout the Danish invasion and up to the Normans.

King Edgar actively supported and enforced all these church reforms, removing secular monks and replacing them by celibate monks with allegiance to St Benedict's rule, rather than to local landlords.

These church reforms were supported by Ealdorman Athelstan, 'Half-King' of East Anglia, who helped refound the monastic houses of Peterborough, Thorney and Ely. These houses had been ruined by the Danish invasions, and at Ramsey, a great new religious house was set up. Although nowadays we would regard these Fenland towns as part of East Anglia, in 970 they were part of Mercia. However, St Etheldreda of Ely had been a Wuffing Princess, and the area around Rendlesham had been a Wuffing royal estate since the days of King Raedwald, who died in 625. Whatever the reason, King Edgar was able to issue a charter to give Ely Abbey the rights to the Wicklaw or Wicklow, an area of five and a half hundreds in East Suffolk around Rendlesham and Woodbridge. Ely soon let them to a tenant in order to get land closer to home.

Despite the fact that the King was pushing Benedictines into minsters across the country, he did not seem to have the lands or the authority to push them into East Anglia, and in particular, into Beodericsworth, or Bury St Edmunds, as we now know it.

The clergy who were in control of St Edmund's shrine may have had wives, and did not follow the new fangled Benedictine strict codes of subjugation to the rule of a monastic order. They were only a small community and would not have been able to resist the King's will unless East Anglia was indeed still a self governing unit, only partially at one with the rest of the country.

Hundreds were first mentioned in the Laws of Edgar in 970, and by the time of Ethelred the term referred to an area of one hundred hides for the purpose of taxation. It has been suggested that originally a hundred could support 100 men, and that some, if not all, of the hundreds dated back to pre-Viking times.

Curiously, most authors say that the Danes have left only a handful of Parish names in Suffolk and five have been identified as Risby, Lound, Ashby, Barnby and Eyke.

|

|

971

|

In the year 653, St Botolph had founded a minster at Iken, (Icanhoe), in Suffolk, on the banks of the River Alde. When he died in 680, he was buried there. With his new foundations being put in place in Mercia, it seems that King Edgar wanted to support them by allocating some of the remains or relics of St Botolph to the new minsters at Ely and Thorney. He gave permission for the saint's remains to be moved. For some reason the removal got as far as Burgh, near Grundisburgh, and there they lay for another 50 years until the time of King Canute.

|

|

973

|

Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury, seems to have delayed Edgar's coronation for 13 years, until the king was 30, the age for ordination of priests. However, it is likely that he was crowned in 959, when he came to the throne, but that the 973 ceremony was to be a new, more religious occasion. The kingship ceremony was made intensely religious at this time, and the King became Christs' appointed, a religious power as well as a secular one.

|

|

975

|

King Edgar the Peacable had sons by two different wives. The oldest son by his first wife was called Edward. His son by his second wife was called Aethelred. In 975 King Edgar died to be succeeded by his young son Edward, who would eventually become known as Edward the Martyr.

King Edgar's will had left 7 hides of land at Chelsworth to Aethelflaed of Damerham. She had been the second wife of King Edmund, and thus was stepmother to Edgar. Aethelflaed herself made a will between 962 and 991, but probably after 975. This will survives as Sawyer Reference S 1494.

Many of her lands were left to her sister for life, and then to a religious institution after her sister's death. These lands included the following clauses which benefitted the monastery at Bury St Edmunds:

" And I grant the two estates, Cockfield and Chelsworth, to the Ealdorman Brihtnoth and my sister for her life; and after her death to St Edmund's foundation at Bedericesworth."

"And I grant the estate at Elmsett to the Ealdorman Brihtnoth and my sister for their lifetime, and after their death I grant it to Edmund."

These lands subsequently passed into the hands of Aethelflaed's sister, Aelfflaed, anf Aelfflaed would in turn leave them in her will, dated between 1000 and 1002, to the holy foundation of St Edmund.

|

|

978

|

The young King Edward was murdered, probably as a result of the feud between the factions supporting the families of each of the wives. Aethelred was placed on the throne, and memories of the bad circumstances around his accession would dog his career. He himself was only a boy of 9 or 10 when he was made King. The country was incensed by the intrigue and many were ready to fight his rule. Aethelred II would rule from 978 to 1016, a period afflicted by constant Danish attacks on the country. After his reign he became known as Aethelred the Unready, but the Old English word "unraed" is believed to have been best translated as 'ill-advised'.

Many types of coinage were issued over the period of his long rule, but moneyers at Thetford issued examples of all these types, as did Ipswich and Norwich. Fewer types were issued at Cambridge. Bury St Edmunds was too unimportant to be ranked as a minting borough at this time. Bury's first coins would not appear until 1048.

Meanwhile King Harold Bluetooth was uniting Norway and Denmark and imposing Christianity by force, building up a strong autocratic state.

|

|

Viking Axes from London |

|

980

|

The Vikings raided the coasts and sacked London. It is possible that these raiders were pagans who were driven out of their homes by Harold Bluetooth and his violent imposition of Christianity.

The period from 800 to 1300 has been called the Medieval Warm period, and in 980 Erik the Red was forced into exile from Norway. Because the climate was improving, he was able to explore northwards, and to establish a settlement in Greenland which lasted until about 1500.

|

|

981

|

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle recorded attacks by pirate hosts from the north on Southampton, Thanet and Cheshire. Although there is no mention of attacks on East Anglia, Dr Lucy Marten has suggested that these almost certainly did take place each year after 980. The east coast was readily accessible to the Danes, and news from East Anglia was not usually reported in the Chronicles written far away in Wessex.

|

|

983

|

Ealdorman Aethelwine of East Anglia had been charge in those lands since 962. By 983 he had risen in status to become the chief Ealdorman in the land. His name would now be at the head of those witness lists that attested to all major wills and Charters. His home was at Upwood near Ramsey, and he was a major patron of Ramsey Abbey, and was regarded as "Amicus Dei", by the monks at Ely, or a Friend of God. Thus, although he was Ealdorman of East Anglia, he lived outside those lands, and his home was in a part of Mercia.

Although he held estates in Wangford Hundred, and had leased the Wicklaw from Ely Abbey, he did not seem to have played a major role in East Anglian affairs. However, he would have received reports from the hendredal representatives of the constant pirate raids on East Anglia, and he would have been involved in deciding upon a response.

|

|

Abbo of Fleury |

|

985

|

In 985 a hoard of 163 silver coins was hidden at Gippeswic. This hoard was disovered in the Buttermarket, Ipswich, in 1863. It could well be that it was deposited in the face of another unrecorded Danish attack on Ipswich and the east coast.

In 985 Abbo of Fleury wrote his 'Life of St Edmund' at Ramsey Abbey, near St Ives. The significance of this event has caused some discussion amongst historians. Was this evidence that Ramsey had some form of oversight and control of the foundation of St Edmund's community at Beodricsworth, as has been suggested? If not, then why was St Edmund's story not written up at Bury?

The answer to this may simply be that Abbo was already well known as a very learned man in a wide variety of subjects, who was eager to become an hagiographer, or writer of saints' lives. He was the best man for the job, and the job was probably commissioned by a major patron of the abbey, such as Ealdorman Aethelwine, the most important Ealdorman in the whole country, who also lived nearby. The country was being raided by Danes on an annual basis, and it would help to improve morale if the story of St Edmund's own resistance to the Danes could be more widely known.

Abbo's book was based on a story told by Archbishop Dunstan as an example to his young monks. Dunstan said that he got the tale from the eye witness report of an old soldier who claimed to have fought for St Edmund. Some translations have described this witness as armour bearer of the King himself, but another reading of "sword bearer", is simply that he carried arms into battle. Abbo's "Life" was written 116 years after the events which it described. Nevertheless, this was to become the basis of all future lives of the saint, which were reworked many times in years to come.

The earliest texts of Abbo do not appear to mention any locations for the battle or for where the saint was laid to rest in a fine church. What he does imply is that the fine church, endowed with many gifts, was erected at the marker at which the saint was originally buried. Like Abbo, we know that the saints remains were by this time at Beodricsworth, now called Bury St Edmunds,

In other texts it is said that Abbo described Beodricsworth as as having been a villa regia, or kinges tun.

|

|

987

|

Some time within the years of 985 and 991, a monk, called Aelfric, wrote an Old English translation of the latin text of Abbo's 'Life of St Edmund'. Aelfric was working at Cerne Abbas, and as texts were passed around the network of monastic institutions, they were copied and re-copied. In his preface, he wrote that:

"Abbo recorded the entire story in a single book, and when the book came to us [i.e., Aelfric], we translated it into English, just as it stands now. The monk Abbo returned home to his monastery within two years, and was soon elevated to abbot of that same monastery. "

|

|

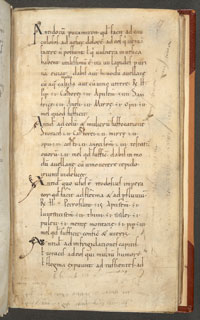

Tenth century manuscript |

|

990

|

According to a legend of the Abbey of St Edmund, recorded many years later in monastic records, around this time Ailwin was appointed guardian of the shrine. The secular priests who had been in charge of St Edmund's shrine for most of the century had been overtaken by new ideas of what was suitable devout religious practice. The rule of St Benedict was being adopted in the new monasteries, and it seems that they were widely held to be more devout and more fitting to guard a shrine. Perhaps the local people were not ready for such a drastic change at this time, and so Bishop Algare put Ailwin, described as a monk, in charge at Bury. It would seem that he merely ruled over the existing college.

The illustration is from the Psychomachia of Prudentius, a popular work copied in many religious institutions from the 10th to the 12th centuries. This page shows the desire for luxury, one of the 'Spritual Combats' that the devout monk had to undergo. This particular document was in the library at Bury Abbey in the 14th century. It is possible that it had been owned, and possibly even produced, by the secular college of monks in Bury around this time. The Bury College of monks may actually have been doing a good job already, before the Benedictines came here.

Dr Antonia Gransden has suggested that it is possible that St Oswald, the founder of Ramsey Abbey may have had a hand in introducing Benedictines to Bury. Oswald died in 992, so if this was the case it was well before the traditional date of about 1020 when Canute is said to have introduced them. Maybe Ailwin was a follower of St Benedict, but perhaps because East Anglia still had its own traditions, the King could not introduce Benedictine monks at this time.

|

|

991

|

By 990 a version of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle has survived from London. This recorded more news from East Anglia and it would seem that suddenly a second wave of Danish attacks assailed East Anglia. In reality it seems likely that raids had been going on here since 980, but had not been recorded in the Wessex Chronicles. In 991 a large, well organised army led by Olaf, later King of Norway, defeated the English at Sandwich, then attacked and ravaged Ipswich. Olaf Tryggvason of Norway seems to have masterminded this attack along with Svein Forkbeard of Denmark. This led finally to the famous Battle of Maldon, commemorated in an epic poem. Olaf had 93 ships and having over-run Ipswich defeated Ealdorman Byrhtnoth or Brihtnoth of Essex at Maldon. At this time Ealdorman Aethelwine was the chief man in East Anglia, but he was probably lying ill at home in Ramsey, as he would die in 992 of an affliction of the feet.

The poem records how a Danish representative stood on Northey Island and suggested that a battle could be avoided if tribute money were paid. Byrhtnoth replied from the mainland side of the causeway that the tribute would be paid in spears, deadly points and tried swords. The battle could not begin until the tide had ebbed sufficiently to allow the armies to meet. The poem records that the grey haired Byrhtnoth was hit by a spear, but continued to fight. Eventually his sword arm was disabled and he was hacked to death along with two loyal bodyguards.

By this time, Sturmer was the main centre in the Haverhill area, sending a famous battalion under their Saxon chief Leofsunu to fight at the Battle of Maldon which took place on August 11th 991.

During the battle when the English leader, Byrhtnoth, was killed, Godric, Godwine and others fled. The poem then records the last stand of the remaining army, quoting words of defiance from several loyal leaders. One such was Leofsunu of Sturmer in this dramatic translation by Bill Griffiths:

"Leofsunu spoke, raised his Linden shield

in defence, responded to his fellow fighter

I swear this. I will not step back

a foot's space. Rather I'll go further ahead

Avenge in battle my benefactor

No one round Sturmer, steady in judgement

will ever need accuse me, now my kind lord's fallen

of making for home, deserting my master

running from war. Better a weapon take me

Point or Blade. Then, in a passion

He fought fiercely. Flight he scorned."

Sturmer remained the chief settlement in the Haverhill area until about 1050.

To show that all classes of men were still willing to fight on, the poem gives more words of defiance to Dunnere, "a simple yeoman". Despite all this bravado, the English are defeated by the northmen.

Ealdorman Byrhtnoth's headless body was recovered to be finally buried at Ely, with a ball of wax to replace his head. Burying the body at the great monastery at Ely emphasises his importance as a symbol of resistance.

His widow was called Aellflaed, daughter of Aelfgar. She commissioned a hanging embroidered with the deeds of her husband. As her will (Sawyer reference S 1486) later recorded that there was a "holy foundation at Stoke (by Nayland), where my ancestors lie buried", it is quite likely that this tapestry was displayed there. No trace now remains of any monastery at Stoke by Nayland.

After these battles, the leadership of Essex and East Anglia was largely wiped out. It was left to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Sigeric, to lead an appeal to raise money to pay off the Danes. This was probably restricted to the areas mentioned, as so far there was no nationally organised way of mounting any response to the attacks. So, the invaders were paid a tribute, or "gafol" of £10,000 and a local peace was made. This was the first tribute payment that had been made for a generation. Later these tributes came to be called Danegeld. This money was raised by taxation, and only served to produce further raids and demands on other areas of England. Danegeld would seriously weaken the economy for years to come.

|

|

992

|

At Ramsey, Ealdorman Aethelwine died. He had been Ealdorman of East Anglia, but had not been at the Battle of Maldon. It is unclear who succeeded him as the major power in East Anglia. But by 1002 the organisation of East Anglian defence was in the hands of a man called Ulfcytel, who would come to be acknowledged as a great military leader.

The English ships were collected at London in order to head off further danish attacks. Aelfric, for unknown reasons, betrayed the King's plan to the Danes.

The Danes invaded again, not having total success despite betrayal of the King's intentions by Aelfric. However, the East Anglian ships were destroyed.

|

|

994

|