Harold is crowned King

Harold is crowned King

January 1066

Quick links on this page

Harrying of the North 1069

Hereward at Ely 1071

Revolt of the Earls 1075

Herfast's takeover bid 1081

Domesday Survey 1086

New abbey church started 1090

New chancel consecrated 1095

Abbot Anselm installed 1120

Bury Bible and town walls 1136

The Bury Cross 1150

Battle of Fornham 1173

Samson becomes Abbot 1182

Jews expelled from Bury 1190

Jocelin begins his Chronicle 1195

Death of Abbot Samson 1211

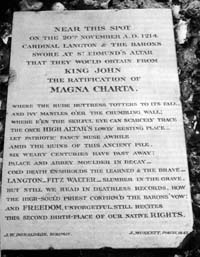

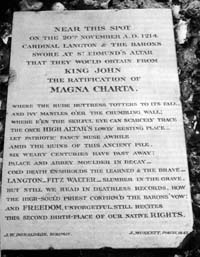

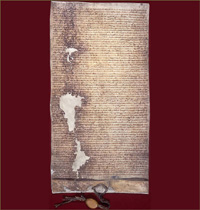

Barons swear an oath 1214

Foot of Page 1216

|

From the

Norman Conquest

to

Magna Carta

1066 to 1216

Pre

1066

|

Please click here to look back at events leading up to the Norman Conquest.

|

|

1066

|

The year 1066 was momentous for England and the English. It would see three major battles take place, itself an extremely rare occurrence. Pitched battles were rare in any event, and three in a year would leave the country weakened and exhausted, whatever the outcome may be. In an agricultural society the disturbance of the farm year by fighting would result in lost or reduced harvests, and the loss of foodstores to hungry armies, whether friend or foe.

It all began when King Edward the Confessor died on 5th January 1066. The Chronicles say that he committed the kingdom to Harold Godwinson. The Witan had gathered to Westminster for the Christmas crown wearing ceremony, and so were on hand to deal with the succession. Within 24 hours the matter was settled, and Harold Godwinsson was crowned on 6th January 1066 in Westminster Abbey. The ceremony was carried out by Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Harold Godwinson had been the second most powerful man in England after the King. King Edward had produced no heir to challenge his position, and Harold was on the spot. The other claimants to the English throne were either Norman or Scandinavian, leaving Harold to seize his opportunity. He had been given the title Dux Anglorum, a title created for him by Edward the Confessor. On the death of King Edward, Harold was apparently the choice of the Witan and the people of the south. The north and Midlands under Earls Morcar and Edwin, may not have been so supportive, as Harold, in fact, had no royal blood.

|

|

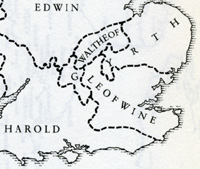

England just before the Conquest |

|

blank |

Morcar was at this time the Earl of Northumbria. He was given this Earldom after Tostig, one of King Harold's brothers, had been exiled. Tostig had ruled Northumbria so badly that his own people rebelled against him, and threw him out in 1065. Harold had been sent to stop this rebellion, but found that there was no way in which the people of Yorkshire would take Tostig back again. Thus he recommended to Edward the Confessor that Tostig be exiled. Tostig never forgave Harold for this.

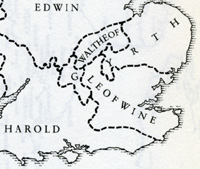

Morcar's own brother, Edwin, was the Earl of an enlarged Mercia. Gyrth, one of King Harold's brothers, was Earl of East Anglia, and another brother, Leofwine was Earl of Essex. Harold himself held the Godwine family Earldom of Wessex.

The map shows the jurisdictions in England on the eve of the Battle of Hastings. You can click on the map to see more of the country.

Duke William of Normandy now demanded the English throne, claiming that he had been promised the succession by Edward the Confessor, and that Harold had sworn a holy oath to accept him as king, back in 1064. Harold had already broken with the Pope by appointing Stigand as Archbishop and the Pope now issued a Bull in favour of the claim of Duke William.

In April, Tostig left Flanders with a fleet of about 60 ships and his Housecarls to raid, terrorize and plunder England's south-east coast. King Harold pursued him, and believed that this was part of Duke William's plan to invade. He expected a summer invasion fleet to follow from Normandy, and sent his own fleet to the Isle of Wight to await William's force.

Tostig, meanwhile sailed to Northumbria to continue his attacks. Harold decided to leave Tostig to Earl Morcar and Earl Edwin. They drove Tostig away, and he now sailed to Scotland and sent to Norway to see what help he could rally with King Harald Hardrada. He wanted to get his old Earldom of Northumbria back from Morcar at any price.

King Harald Hardrada was king of Norway. He came to rule the whole of Norway when Magnus the Good died in 1047. The Danes, who had also been ruled by Magnus, refused to accept Hardrada as King. Hardrada spent twelve years trying to conquer Denmark, latterly in the hands of Ulf, cousin to Harold Godwinsson. In the end, he failed and signed a pact with King Swein of Denmark in 1063.

Harald Hardrada believed that King Magnus of Norway and Harthecanute, King of England, had agreed in 1038, that each would inherit the other's kingdom, depending on who died first. This was the basis of his own claim to England.

Tostig, the renegade brother of King Harold of England, now sent word to Norway and persuaded Hardrada that he would be supported by English Earls if he would only invade England.

Soon after, Hardrada and Tostig invaded in the North from Norway. First they burned Scarborough. The attack and burning of Scarborough occurred on Friday, 15th September 1066. Messengers, riding their small ponies, brought the news to Harold within four or five days, probably by the 19th or 20th September.

Meanwhile, on 19th September, the Norwegian fleet anchored in the River Ouse at Riccall, 12 miles from York. York was the capital of the Earldom of Northumbria at this time. The Earl of Northumbria, Morcar, as well as his brother, Edwin, Earl of Mercia, were both present in York. Edwin only had a small force with him, and together they could only muster a force of a few thousand to intercept the invasion, which they did on 20th September at the Battle of Fulford Gate, also called Gate Fulford, just outside York.

Tostig had been Earl of Northumbria until his exile, when Morcar had been invited in to replace him, and he was determined to take it back. Although Earls Edwin and Morcar chose the battlefield, they were defeated by the invaders. York now gave up without further fighting, and agreed to support Hardrada in return for not being sacked by the Vikings. They also agreed to deliver 100 hostages to Harald Hardrada on Sunday, 25 September, at Stamford Bridge.

In the south King Harold of England had to decide whether to continue waiting for the Norman invasion, or to ride north against the vikings. He knew that on 12th September, a storm in the channel had damaged his own fleet, and probably William's as well, and perhaps he gambled that there could not be an invasion from Normandy for some weeks yet.

On 20 September, the day of the battle of Gate Fulford, Harold and his army of 6,000 set out for Yorkshire. They must have been mounted as they reached Tadcaster On Saturday, 24th September, only four days after leaving London. This was just 10 miles from York, meaning that they must have made 50 miles a day. They rested, and then moved into York, where they heard all about the surrender and its terms, and also that the invaders did not know they were here. The King decided to let the enemy go to Stamford Bridge, where he would attack them.

The vikings only had two thirds of the army at the Bridge, and they had mostly left their heavy armour at Riccall. They were taken by surprise, and overwhelmed.

Harald Hardrada and Tostig were both killed at the battle of Stamford Bridge. Hardrada's fleet of 300 ships was captured, and only 24 ships escaped. The Norwegian invasion was defeated.

King Harold now set to, and rested his men, and prepared the captured ships to sail back south. While making preparations, on the evening of 30 September or in the early hours of 1st October, he got the shock of his life. News came that Duke William had landed on 28th September.

|

|

Williams invasion force

Williams invasion force |

|

blank |

By late September Duke William had assembled a fleet of 700 ships, enough to transport approximately 12,000 troops and 4,000 horses. The ships had no oars, and only simple sails, in order to carry as many men as possible on a one way trip across the Channel.

On 27th September, the long feared attack of Williams' fleet had been launched from the Somme estuary. They landed 7,000 men unopposed at Pevensey but quickly moved to a new base at Hastings.

|

|

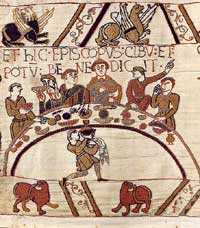

William feasts at camp in Hastings

William feasts at camp in Hastings |

|

blank |

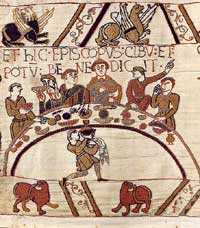

Arriving at Hastings, the Bayeux Tapestry shows that at least part of the town was burnt. But William took it over, and new fortifications were built at Hastings. William now had time to celebrate a successful landing in England. William knew that the English army was in the north to fight off a Norwegian invasion. Indeed, for some time William did not know if he would be fighting the English for the crown, or the Norwegians. In any case, he had at least a fortnight before either defending army could reach him.

King Harold, camped outside York, had no choice but to rouse his men from their victory celebrations and return south on 1st October. He reached London on 5th October, and sent out for the fyrd to gather. His army which had followed him up to York slowly made its way south to catch up with him over the next few days. Morcar and Edwin stayed in the north. No significant number of men from north of the Humber would fight at Hastings. They came from the south to join Harold for this battle. A later cleric, Wace,wrote in his "Roman de Rou" (1160-1174) that

"they came from ....Bury St Edmunds and Suffolk, ..Norwich and Norfolk, ..from Cambridge and Stamford." They were led by the Earl of East Anglia, who was Gyrd or Gerth, the brother of King Harold.

King Harold left London with a mounted force on 11th October. The footsoldiers followed on. It was not until 14th October that he could get the army assembled at Hastings. He had perhaps 8,000 men, and gained a good position bottling William up. William was taken by surprise, but quickly moved to accept battle, something Harold had not expected.

Harold's heavily armed Housecarls and thegns made up the front ranks with their shield wall. They had two handed axes, kite shaped shields and armour. The fyrdmen were the lesser men, called from their homes to fight in great numbers, and were armed with home-made swords, maces, spears, daggers, and sharpened farm tools and clubs. Their armor usually consisted of straw stuffed under their shirts. The English, even those with mounts, fought on foot. The French had 3,000 knights who fought on horseback. The French had 1,000 archers, the English had none. With 4,000 infantry, the French numbered 8,000 in all.

Count Alan Fergant of Brittany commanded his 2,500 Bretons on the left flank.

Roger de Montgomerie commanded the 2,500 French and Flemish troops on the right flank.

Duke William took the 3,000 Normans in the centre, giving some to his brothers, Robert, Count of Mortain and Bishop Odo.

Harold had 8,000 infantry along Senlac Ridge. He might have hoped for more if he had more time for them to arrive. He intended to let the enemy wear themselves out attacking up a slope, until he could counter attack.

Just after 9 a.m. on 14th October 1066, the French attacked. They had heavy losses and fell back, but some of the Saxon fyrd foolishly broke ranks to chase them, and were slaughtered.

The second attack came at noon, and attacks now continued. Harold's younger brothers, Earl Leofwine and Gyrth, Earl of East Anglia, were both killed by Norman cavalry breaking into the lines. By 5pm they had fought for seven hours, and the French were achieving their aims.

So far the French archers had been firing at the shield wall, getting nowhere. They were now told to fire up into the air, with devastating results for the English. The shield wall was effectively destroyed from above, and a band of French knights broke through, reached King Harold, and hacked him to death.

|

|

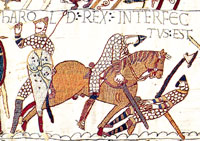

Death of King Harold

Death of King Harold |

|

blank |

The fighting largely ended when Harold was killed, but whether he was ever hit by an arrow is uncertain. He was hacked to pieces by Norman Knights who punched through the arrow weakened shield wall. The Bayeux Tapestry shows a figure under the word "Harold" with an arrow in the eye, but next to him another figure is attacked by mounted knights, under the words "is killed" or "interfectus est". The housecarls seem to have fought on to the death, while the fyrdmen fled.

Duke William had won the battle, and awaited a counter attack. Earls Edwin and Morcar were finally marching south, but turned back when they got the news about Hastings.

Leaving Hastings with his army, William proceeded east up the coast to Romney, which he burned, then to Dover, which he plundered, and then to Canterbury, which surrendered to him and which he did not burn or plunder. Winchester then surrendered so he moved towards London. As he approached, he was met by a delegation of Londoners, by Earl Edwin and Earl Morcar, English nobility and Bishops. They decided to submit at Berkhamstead to avoid further destruction. Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester was in the party that surrendered, and by the time of William's death in 1087, he would be the only English Bishop left in his post.

On 25th December 1066, William the Conqueror was crowned King of England by Aldred, Bishop of York, but apparently he still expected trouble. At his coronation in Westminster Abbey, his soldiers were so on edge, that they mistook the acclamation of the king to be war cries, and set fire to the city. William was said to have trembled at the smell of smoke, and the sounds of confusion outside.

He had conquered a rich and well organised country with the minimum of bloodshed, although it must be said that he had several lucky breaks along the way.

The surviving hierarchy of the south of England quickly submitted to the new King. The office of Staller, or Constable, had been instituted by King Canute, and Edward the Confessor had six stallers. These were men whom he trusted to be his representatives in the provinces. Ralph the Staller now threw his lot in with William. Robert Fitzwymark of Essex was another staller who had even given William military advice before Hastings ever happened.

In 1066 William was glad to have their support. England generated large tax revenues, and was well governed, and he wanted to let this continue. But he had to reward his own men for coming to England. They had largely financed themselves, and at first only those lands of English who died at Hastings was parcelled out to his Norman followers.

By 1066 the Abbey of St Edmund in the town we now call Bury St Edmunds was in possession of large numbers of landholdings throughout the Liberty of St Edmund, and much further afield in other parts of Suffolk, and in Norfolk and Essex. The Abbot Baldwin would, no doubt , have immediately pondered how best to preserve those possessions from the depradations of the new king and his supporters. By 1086 he would find that although a few of the abbey holdings would be lost, new donations would continue to come in.

You can see maps of the Abbey holdings, both in 1066 and by 1086, by clicking here:

Maps of Abbey Landholdings 1066 and 1086

William was not known as the Conqueror until much later. At the time he was known as William the Bastard. His father was Robert, Duke of Normandy, but his mother was the daughter of a prosperous, but socially inferior, Falaise tanner. After bearing Duke Robert two children, she was married off and produced two more sons by her new husband, one of whom was Odo, Bishop of Bayeux.

When William was born, in 1027, Church teachings were making bastardy a handicap, but Duke Robert had no legitimate sons and so in 1034 he had to recognise William as his heir. William became Duke at the age of nine in 1035 and experienced twenty years of bloodshed and intrigue before he emerged as undisputed ruler of Normandy.

The Abbot Baldwin at St Edmund's Bury was a French monk and a noted physician. He was royal physician to Edward the Confessor and was to perform the same function for William. Not only did William the Conqueror leave him in his post, together with all existing rights and privileges of the Abbey, but there was no Norman Castle built to dominate the town, and no disruption of the sort suffered elsewhere in Saxon England.

|

|

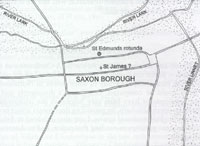

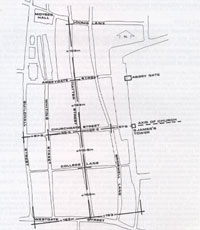

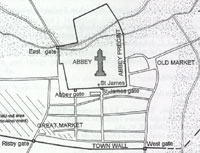

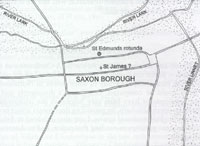

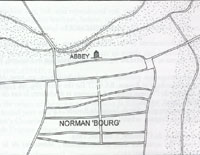

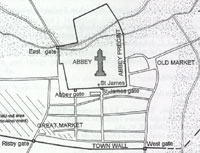

Bury 1066 by Bernard Gauthiez |

|

blank |

Bury's population was probably about 1,500 with possibly 20 monks in residence. According to the Domesday Book, Bury was valued at £10 in 1066 with at least 310 householders worthy enough to be recorded. The relevant extract is as follows:

"14, ('Lands of St Edmund')

167

In the town where St Edmund the glorious King and Martyr lies buried, Abbot Baldwin held 118 men before 1066 for the monks' supplies.

They could grant and sell their land.

Under them, 52 smallholders from whom the Abbot could have a certain amount of aid.

54 free men, somewhat poor;

43 almsmen; each of them has 1 smallholder.

..............

Value of this town then £10; now £20.

It has 1½ leagues in length and as much in width.

When the Hundred pays £1 in tax, then 60d goes from here for the monks' supplies;

but this is from the town as it was before 1066."

The arithmetic is 118 plus 52 plus 54 plus 43 plus 43 equals 310.

The illustration shows the old Saxon town layout as envisaged by Bernard Gauthiez before Abbot Baldwin embarked upon major construction works both at the monastery site and in the town.

The Normans brought their forms of government which we would call feudalism. The abbot became a tenant in chief of the king and a baron of the realm. Under this system he would be obliged to supply the king with 40 knights in time of war, and to meet other feudal duties to the king.

It does, however, seem likely that whatever privileges and rights were still enjoyed before 1066 by the family of Bederic in and around Bury, these would have been lost by right of the conquest. The new King took over all such rights and it appears that he would have given them to the church of St Edmund or to the abbot. In other places he would have given such rights to one of his Norman Lords who had helped with the invasion. However it is not at all clear whether Bederic's kin still had many local rights following the grants made to the church by Cnut and the pre - conquest kings.

The convent of monks retained their rights over the town of Bury, outside of the abbot's barony, and the abbot's connection with the town itself was therefore nominal. The Sacrist represented the convent and was therefore, in practice, the lord of the borough. The Cellarer was the lord of the manor of Bury, and exercised the convent's rights over the town fields and agriculture, rights to the market, and control of the digging of chalk and white clay. His job was to provide provisions for the abbey. These rights often came under dispute over the years because of their complex nature, and often obscure origins.

Most of the town now apparently belonged in one way or another to the abbey. We know that in later years there were some land holdings within the town which were owned by external landlords. These included the Manor of Maydewater, in the area known today as Maynewater Lane. This was made part of the Honour of Clare, and a smaller holding belonged to the Manor of Lidgate. However, it is unclear when these landholdings were ceded to outsiders. There will be no mention of these in the Domesday Book.

The continuity around Bury contrasts with the more widespread disruption of land ownership around Haverhill and Clare. After the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror granted lands in Haverhill to the Bishop of Bayeux, from Normandy, to Richard son of Gilbert (also later to become known as Richard of Clare), to the "Lands of St Edmund" and to Tihel of Helean (Helion), who was also granted Helions Bumpstead.

There was already a church in Haverhill owning five acres of land. This must be the Burton End church, dedicated to St Mary.

The population of Haverhill, however, was small and out of the 54 male inhabitants only 19 were free men. There were 25 smallholders and "always ten slaves", and 27 pigs were recorded.

Ipswich was the largest town in Suffolk in 1066, but by 1086 it would be severely depopulated, probably because it was associated with resisitance to the Norman Conquest.

Thetford was also a town of first rank at this time, with a population of 4,000 to 5,000. It had a monastery and a mint for which it paid the king £40. It had twelve churches, but, like Ipswich, it would not prosper after the conquest, and would decline from the 943 burgesses it had in 1066 to 720 by 1086.

Norwich was by 1066 one of the largest and most important towns of Saxon England. It had 1320 burgesses, which is thought to indicate a population of about 5,000 to 10,000 inhabitants. It was, like Thetford, a busy inland port, but much larger, with extensive river wharves and storehouses.

|

|

1067

|

William soon left England with hostages and treasure, to return to Normandy to mind his affairs at home. Laws, wills, and legal writs continued to be written in Old English, and the English administration was left largely in place.

Gyrth, the Earl of East Anglia, had been killed at Hastings, but his title was now given, not to a Norman invader, but to Ralph the Staller, who was a high official of the conquered English court. Ralph was part Breton, and had French lands, so this may have helped his position. Ralph was born in Norfolk and already held land in that county, in Suffolk and in Essex. Men like him had been close to Edward the Confessor, who himself had spent so long in Normandy, that when he became King of England, he had filled his court with Normans and Bretons.

William did, however, insist upon one legal technicality. This was that his reign had begun, de facto, back in January, 1066, upon the death of Edward the Confessor. He regarded Harold as an illegal usurper, and therefore he could regard all of Harold's followers as traitors to him. Later he would build on this fiction to justify widespread confiscations.

Following the conquest in 1066 there was some rearguard opposition. Winning the Battle of Hastings had not persuaded everybody that William was rightful King, or that he controlled the whole country. For most of 1067, William was back in Normandy, leaving Odo of Bayeux and William FitzOsborne in charge. There were risings on the Welsh border and in Kent. William had to return to England to subdue a more serious uprising in the West Country.

The wild woods and fens were used to hide bands of men, while Norman soldiers roamed freely in these places, looting, confiscating lands, and killing. In return, individual Normans were being attacked and killed by English outlaws. A mass uprising seemed possible.

At Bury we can assume that the town was safely held by Abbot Baldwin for King William for a number of reasons. Firstly Baldwin was himself a Norman, and so could negotiate freely with the King and Norman nobles. He got all the Abbey's privileges confirmed, and so could afford to sit tight. In turn the King could trust Baldwin because of his background. The monks could accept the authority of the new King because he had been properly anointed before God, and, in any case, it could be argued that Victory by Arms proved that this was God's will. Elsewhere, Abbots were disposessed, and replaced by Normans, and transition was more painful.

It is assumed that the king started to build a great keep or castle at Norwich. Work was said to have begun by destroying 100 houses in that thriving saxon town to make room for it. Work probably went on for about four years until this first wooden castle was completed. It seems that the stone keep was not built until the 1120's by Henry I.

|

|

Wooden Motte and Bailey

|

|

1068

|

With lawlessness growing, William returned from Normandy and issued a decree asking for the formal submission of the northern magnates. Failing to receive this, King William raised his army and went on campaign. Wherever he stopped, he built a new castle. 1068 saw hastily erected defences thrown up by the conquerors on all sides. There was no time to build in stone. Earthworks and wooden palissades were the order of the day.

William's campaign went to Warwick, Nottingham, York, Lincoln, Huntingdon and Cambridge, building an earthen mound, or motte, with a wooden castle, or bailey, at each location. At York, William Malet was made Sheriff. Malet had apparently not yet been given his lands in Suffolk.

Part of these first attempts to subdue the countryside took place at Cambridge, when the king destroyed 27 houses to erect a castle on the north bank of the river there. The motte or castle mound remains today next to the Shire Hall.

Towns now became centres for Norman control of the countryside. At Thetford the town was viewed, not as a rich trading asset, but as a hotbed of Danish sympathisers. A huge motte, or mound, was built within the old Iron Age fort's earthworks, topped by a bailey. A completely new Norman suburb was built to the west of the castle, and on the northern side of the town river. The older borough to the south of the river would fall into decay. By 1086 the town of Thetford would have lost a quarter of its population.

Ipswich had also had Danish sympathies, and a Norman castle was also erected there, probably near today's Elm Street.

At Castle Camps, Aubrey de Vere built a large moated earthwork to enclose his headquarters.

The revolt was stamped out from these strongholds. The lands of defeated rebels were confiscated and given legally to William's followers.

In East Anglia the towns of Bury St Edmunds, Norwich and Dunwich would become prosperous as favoured Norman strongholds, while Ipswich and Thetford would be deliberately downgraded and neglected. French settlers were encouraged to come to these towns and set up trade links with home.

After this campaign, William again returned to Normandy.

Hereward the Wake was not one of the Wake family of Northamptonshire. The Wakes seem to have "adopted" him into the family some centuries later. Trevor Bevis says he was the son of the Saxon lord, Leofric of Bourne, following the "De Gestis Herwardi Saxonis" but Peter Rex dismisses this idea. As the nephew of Abbot Brand or Brando of Peterborough, Rex argues that Hereward had Danish blood, and that Brand's older brother, Asketil of Ware, was likely to be Hereward's father. He was also said to be a nephew of Ralph the Staller, who was part Breton. Either way he had noble relatives and was heir to a very rich and powerful man.

It is agreed that Hereward was an unruly youth, stirring up "sedition and tumult," even to the extent that his father had him thrown out of the country in 1063. Hereward made his name as a soldier fighting in Flanders and the Low Countries, and was out of the country when the Norman invasion occurred. The Norman Conquest would have threatened his inheritance, and he needed to check up on it.

It is likely that Hereward the Wake returned to England in 1068 to visit his uncle, Abbot Brand of Peterborough. He may have got involved in some attacks on Normans in this visit. He found that some of the family estate was safeguarded by Abbot Brand taking it over for the Abbey at Peterborough, but much was given to Hugh de Beauchamp by King William. But he soon went back to fulfill commitments to fight in Flanders. Hereward came home for good in 1069 when Abbot Brand died in that year, putting his remaining fortune in peril.

|

|

1069

|

In January, William's newly appointed Earl of Bamburgh was killed by local people. They had installed Aedgar the Atheling as their "king", calling upon York, and Swein, king of the Danes, to help them establish a free kingdom of the north.

England still had a strong Danish presence, particularly in East Anglia, the old Danelaw. Danes were dispossessed by Normans even more readily than Saxons, and so there was some local support for the three sons of Swein of Denmark when they attacked England in 1069.

The Danish fleet landed first at Sandwich in Kent. They sailed on to Ipswich, then Norwich, and into the Wash. They proceded into the Humber, and up the River Ouse to attack York. At York, William Malet was holding the castle built there in 1068 by the King. The Danes attacked York and killed many people, capturing William Malet in September, 1069.

King William marched to York, and built a second castle there. He stayed until Christmas, where he wore his royal crown to emphasise that he was King in Northumbria, as well as in the south.

At some point, William Malet escaped from Danish captivity, and it seems that in late 1069, or in 1070, he found refuge in East Anglia.

Another Danish force invaded East Anglia. Despite the remaining Roman defences at Colchester, the Danes captured and burnt the town. Finally they were defeated near Ipswich.

By the end of 1069, the attitude of King William to England had hardened considerably. He had been dragged back here several times to put down one uprising after another, and he was losing patience. He mounted a punitive expedition after Christmas 1069 which has been called the Harrying of the North.

He first marched on Durham and retook it from the rebels.

|

|

1070

|

After recapturing Durham and pacifying the area of Northumbria, King William extended his reprisal march to the West. By February he had marched across the Pennines to take Chester, where he built yet another castle.

William's march through the north was said to have devastated thousands of square miles. By the time of Domesday in 1086 the north still apparently remained a depopulated wasteland. Just how much destruction occurred is difficult to assess.

After 1069 William started to depose some Bishops and Arch-bishops, where he thinks they have not been active enough in helping his cause. He abandoned the use of Old English in his writs and laws, bringing over French clerics, who were used to using Latin. He decided to treat England as a conquered land, to be governed by force if they would not accept him as lawful ruler.

At Lent in 1070, King William decreed that all monasteries should be plundered of the riches placed there by the local nobilities. This included Ely, which showed no willingness to co-operate, as well as at St Edmundsbury, where things had been very quiet under Abbot Baldwin, the French Benedictine, who had ruled there since before the conquest. Bury has no record of having been plundered under this ruling, but it seems likely that Baldwin must have quietly gone along with the decree.

|

|

Archbishop Stigand now deposed

Archbishop Stigand now deposed |

|

blank |

At Easter 1070, the King set about deposing Bishops and Abbots. Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury, had crowned Harold at Westminster Abbey, and had been close to Canute's Queen Emma, but was now evicted. Stigand had angered the King by placing his treasury at Ely, for the moment out of William's reach. Stigand's brother Aethelmar was Bishop of East Anglia, and would soon suffer as well.

King William's new heavy hand provoked further local resentment.

Part of this rebellion was an attack on Peterborough by Hereward the Wake. Hereward was by now a seasoned campaigner, having been fighting in Flanders for the last seven years. His Uncle, Abbot Brand of Peterborough, had been safeguarding what he could of the family lands, but had died in 1069. As was his new policy, King William now installed a French abbot, called Turold, to hold Peterborough.

Part of the Danish fleet had left the Humber, and now entered the Wash. The rebels in the Fens made contact with them, hoping to enlist them in actions which would help their cause. They would be paid by the plunder they took.

Turold was a fighting monk, and he was sent to Peterborough with 160 knights, expecting trouble. Tenants of the abbey, which included Hereward, invited the Danes to help seize the monasteries treasures to avoid them falling into Norman hands. When Turold arrived he found the abbey stripped of its possessions. The rebels had directed the Danes to attack Peterborough, rather than Ely, which remained sympathetic. The abbot of Ely was Thurstan, who had been appointed by Edward the Confessor, and was close to the now deposed Archbishop Stigand.

Turold soon got Peterborough abbey functioning again, but it was now to supply 60 knights to support the King. In order to fulfill this duty Turold handed out fiefdoms around Peterborough to Turold's family and Officers of his force. Herewards fears for his lands were thus confirmed.

William's new policy of heavy handedness extended everywhere, whether there had been local rebellion, or not.

The Anglo - Saxon Bishop of East Anglia had been Althelmaer since 1052, with his simple wooden cathedral and headquarters in the obscure and remote village of Elmham. It had been there for centuries. The post conquest Norman Archbishop Lanfranc now had carte blanche to sack him, and replace him by Herfast, or Erfast, a Norman royal favourite. Norman religious ideas were to decry simple worship, and they demanded great stone churches in the heart of the largest towns.

Archbishop Lanfranc also issued an injunction that bishoprics would now only be assigned to major towns.

For the new Bishop Herfast, this meant choosing between Thetford, Norwich, Ipswich and Bedericsworth, or St Edmund's town, as it was now thought of. Thetford was the safe bet, but Erfast had his eyes on the established and wealthy abbey at Bury.

This conflict between the Bishopric and the Abbot of St Edmunds would rumble on for several decades.

|

|

St Etheldreda

|

|

1071

|

The revolt of Hereward the Wake in 1070 and 1071 has been said to be a minor affair by contrast to the northern revolts, but has attracted more attention from some writers. Trevor Bevis thinks that of all the revolts, "that occurring in the fens was the most serious." Peter Rex calls Hereward "the last Englishman."

Following his raid on Peterborough in 1070, Hereward was a hunted man. He believed that he could seek refuge on the Isle of Ely, and that he would be accepted by the monks there. The monastery at Ely was very old, and was founded by St Etheldreda, or Audrey, in 673. Ely had been besieged by Norman nobles, on and off, for three years, but they had made little effective progress. By now King William had decided to strip the monasteries of their wealth and charters, together with any wealth deposited there for safe keeping by English landowners and merchants. There were no banks, and often the local abbey was the only place thought safe from banditry of any kind.

|

|

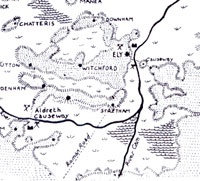

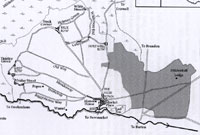

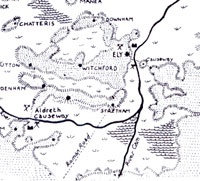

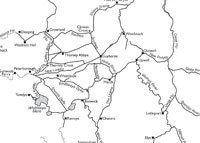

The Fens in 1071

The Fens in 1071 |

|

blank |

At this time the water table in the Fens was probably 30 feet higher than it is today, with swamp and marshy, reedy waterways the norm. There was no agriculture of the type seen today. Instead it was a vast fishery, with some reed cutting where possible, and grazing in the summer months. Eels were widely trapped, even giving Ely its name. Ely was an island with four main landing places or hythes. Even at Bury the River Lark was deeper than it is now, with the town almost surrounded by the waters of the Lark, Linnet and Tay Fen, and their flood meadows. The River Lark then joined the Ely Ouse at Prickwillow.

The Isle of Ely itself was a haven by comparison to the surrounding Fen. The isle covered seven miles by four miles and enjoyed a high standard of farming on its drier rich soil. The Abbey itself was a rich endowment, and the town of Ely was substantial.

When Hereward arrived it seemed possible that Ely could become a centre from which England could be regained. A Danish fleet had landed on the Humber under King Swein, and been welcomed by the English at Ely. Hereward added his own force to the garrison, and may even have used Ely as his base when he had earlier attacked Peterborough, and sacked the abbey with the Danes.

Once King Swein had loaded up with treasure from Peterborough, it seems that he left Hereward and Ely in the lurch. King William promised King Swein of Denmark that he could keep the Peterborough spoils without fear of reprisals, if only he would return to Denmark with his force. By this arrangement Ely was in practice reduced from a national threat to a regional problem.

All Hereward could do was call upon his friends and relations to come and help him defend Ely. Among them was Ordgar, the Sheriff of Cambridgeshire and in some authority over the Liberty of St Edmund under Edward the Confessor and King Harold. Others were Thorkell of Northamptonshire, son of Thurkill the Tall, Siward of Maldon, Thorbert of Freckenham, and even monks like Brother Siward from St Edmund's town, and Archbishop Stigand. Hereward's followers all had to swear an oath of loyalty to St Etheldreda, or St Audrey, the patron saint of Ely. Even the Earls Morcar of Northumbria and Edwin of Mercia, who had been somewhat shaky followers of the King, joined Hereward. Bishop Aethelwine, the outlawed Bishop of Durham, also arrived with men. They all dug in at Ely and prepared their defences.

King William knew he had to finish the matter. He had seen off the Danes, and had made a peace with the King of France to safeguard his homeland in Normandy. In the Autumn of 1071 he ordered out an army and some naval forces to blockade the Isle of Ely, and began work on a Causeway across the Fen into the Isle. From Norfolk and Suffolk came William de Warenne, from Castle Acre, Richard FitzGilbert from Clare, and William Malet from Eye. Earl Ralph Wader, a Breton, holding Norwich for the King, does not seem to have been summoned. King William mustered his army at the new castle at Cambridge, then sailed up the River Granta to Reach and then to Aldreth. He may also have sent a force to try to attack via Stuntney.

Early attacks failed, and a knight called Deda was taken by Hereward, entertained and then sent back to King William. While a new causeway was being built Hereward counter-attacked and set fire to the reeds, causing the Normans to scatter, and some to drown in the swamps. But it was clear that the King meant to see it through.

Hereward's allies now gradually deserted him. The King may have tried to arrange deals with them. He also began to confiscate Church lands. Hearing of this, Abbot Thurstan secretly switched sides to support the King to avoid further loss of his abbey's wealth.

It seems that Thurstan waited until Hereward went out on a raiding party, then allowed the King to be directed through the Fens with a thousand knights and associated baggage. A defended position quite close to the Isle of Ely took seven days to break through, using siege engines mounted on flat bottomed pontoons or barges. This attack probably took place along the Aldreth Causeway, an obvious approach that would have been strongly defended. As William now started to enter the Isle itself, Earl Morcar surrendered himself, hoping for a deal, only to be eventually thrown into prison. After a few more skirmishes, the 3,000 defenders fled or surrendered. Edwin, it seems, also surrendered but was killed. William had some imprisoned, others lost eyes, hands or feet, but the ordinary people were unharmed, as part of Thurstan's arrangement beforehand.

Hereward himself was not captured at Ely. He may not even have been present when William finally attacked, otherwise resistance might have been stronger. His fate is quite obscure. One story is that he was forgiven by the King, and went on to serve him well for many years. Given William's propensity for punishing his enemies, this seems unlikely. Perhaps he fled back to Flanders, where he was well known, and had friends.

William Malet died in the marshes on this campaign helping King William in his blockade of the Isle of Ely, where Hereward had set up his stronghold. Followers of the King like the Malets needed their rewards for their losses in these battles, and these would soon follow.

By 1071, Erfast had been consecrated as Bishop of Elmham. The diocese was due to move its headquarters to Thetford, but Erfast wanted to move in on Bury. Baldwin went to Rome to defend his abbey against this takeover. The Pope gave the abbey the privileges it sought, as well as a porphyry altar but the dispute continued. Erfast only withdrew his demand after his eye became septic and Baldwin, who had been royal physician to three kings, would only help him in return for withdrawal of his claim to Bury.

Up until this time the abbey of St Edmund had felt under the special protection of the English Crown. Its greatest privileges over the town and the area of West Suffolk had been granted by successive Kings. Now, in 1071, the Abbot felt that he needed to appeal to the Pope to defend his position. Pope Alexander II merely seems to have confirmed those privileges already granted to the Abbey by the Crown, but perhaps the Crown was by now becoming unreliable as a protector. The Pope confirmed the Abbey's exemption from episcopal authority, effectively bypassing the English Bishops and Archbishops, and giving St Edmund's a direct line to the Papacy itself.

The headquarters of the East Anglian diocese would remain at Thetford until around 1098 when it moved to Norwich.

In Thetford it is believed that Erfast set up his cathedral on the site where Thetford Grammar School stands.

|

|

1072

|

By 1072 William was in full control of all England.

At Ely he extorted a thousand marks from the Abbey to restore them to his favour, as punishment for harbouring the rebels. No doubt the result would have been worse for them had Abbot Thurstan not switched side and helped the King in his final assault. After this Abbot Thurstan embarked on his own extortion, recovering some of the Abbey lands for Ely by threats of excommunication and curse.

There was now another round of land confiscations to punish those who had been in the resistance at Ely. In East Anglia this may have meant that the aftermath of the battle for Ely had a bigger impact upon the local population than did Hastings. King William was no longer in a mood to be reasonable, and he had his own men to reward for the capture of Ely. It was not just dead enemies who lost out.

Hereward's lands went to Ogier the Breton. Siward of Maldon lost his property. Aedrich of Laxfield lost his property to the Malets. William Malet was dead by this time, so he may have gained Laxfield a little earlier, but his son, Robert Malet, was ready to take over.

How much land Malet owned in East Anglia before 1071 is unclear. He probably came here after his escape from the Danes at York. He was a trusted henchman of King William and owned estates in Suffolk taken over from the Saxon, Edric of Laxfield. Certainly his memory was rewarded by further lands after Ely, and his great estate now established. It was called the Honour of Eye and contained over 200 manors in Suffolk as well as a number in other counties. After the death of William Malet it passed to his son, Robert Malet.

Malet had built a Castle at Eye by this time, complete with a town layout and a new Eye market, ruining Hoxne market in the process by the competition. In order to slip into the shoes of the previous Saxon overlords, many of the new castles built by the Norman aristocracy were placed on the site of the older Saxon manor houses. It is very likely that remains of Edric of Laxfield's manor house lie below the motte and bailey built by William malet at Eye.

Another estate in Suffolk, the Honour of Haughley, was probably also set up after the land forfeitures following the Ely uprising. Guthman of Haughley lost his estates to Hugh de Montfort.

Lawsuits between 1071 and 1075 show that the Abbey at Ely lost many small parcels of land to encroachment by the new Norman Lords, and to neighbours, like Finn the Englishman, taking advantage of the confusion. One case was over six acres at Rattlesden.

We can also expect that St Edmund's Abbey also lost out during this period, to some degree, but Abbot Baldwin did not attempt to regain these by going to law, and upsetting his new neighbours. Most of Bury St Edmunds had belonged in one way or another to the abbey, but the largest exception to this was the Manor of Maydewater, in the area known today as Maynewater Lane. This was made part of the Honour of Clare, and a smaller holding belonged to the Manor of Lidgate. It may have been at this time that these exceptions came about.

Of the 10,000 men who crossed the Channel with King William, some 2,000 were rewarded with grants of land. Within a short time, ten of King William's relatives owned 30 per cent of English land. Prominent among them in Norfolk were the Bigod and Warenne families. The Bigods also had great estates in Suffolk.

The Normans could now begin to enjoy their new estates.

The 1066 invasion of England had been financed by the Jewish moneylenders who lived in Normandy. Although they were a necessary part of the King's economy the Jews lived under many restrictions. They were necessary to an ambitious king as the Bible forbade Christians from lending money in order to receive interest. The Jews could therefore make a living by becoming moneylenders, an occupation despised by the Church, but necessary for a developed economy. The Jews could not bear arms or own freehold land.

Once the Norman way of grandiose living came to England, the King and nobility needed ready cash to pay for the building of their castles and churches. It is supposed that the Jewish communities in England came here in the wake of the Norman Conquest in order to provide the finance for the massive redevelopment of English architecture presided over by the King William I. The Jews did not have a place in the feudal hierarchy as such. They were under the direct protection of the King, thus avoiding the need to give feudal duty to the local barons. However, when a Jewish financier died, most of his estate was forfeit to the king, and in life, the king could direct him to go anywhere in the country to provide financial services to his lords. The king also taxed their profits, and might at any time make over a tenth of his income from the jews. Jews were expelled from Bury St Edmunds in 1190, and from the whole country in 1290.

|

|

1073

|

Hildebrand became Pope Gregory VII and he tried to cleanse the church of corruption but also intended to spread papal authority throughout Europe. In effect, he wanted a united Europe, but the secular kings had no wish to be stripped of their power.

He also threatened to anathematize any priest who failed to give up his wife.

By 1075 he decreed that no person should attend a service by a priest who was married.

|

|

1075

|

The first post-Hastings Earl of East Anglia was Ralph Wader, or Guader, also called Ralph the Gael. Although he was at least part Breton French, he had been a Staller, an important official at the court of Edward the Confessor, and had been quick to acknowledge William as the new King. Ralph the Staller had been made Earl of East Anglia after 1066, but died in 1069, when the Earldom passed to his son, also called Ralph.

Ralph, the son of Ralph the Staller, held Norwich castle for the crown. He had not been called to the fight with Hereward, and thus missed out on the victors' spoils. Possibly his being Breton, rather than Norman, may have meant that his loyalty was in some doubt. There is also the possibility that he was related to Hereward, and thus not to be trusted. In 1075 he proved William right by joining with two other of William's Earls to challenge the King's authority.

This event is known as the Rebellion of the Earls, but it included a major contribution by the Danes once again.

In 1075, King William was abroad, as he usually was from 1071 to 1075. The country was left in the hands of Archbishop Lanfranc. The absence of the King encouraged plotting. The plot seems to have begun with a wedding ceremony held at Exning, where Ralph married Emma, the daughter of William FitzOsborne, and the brother of Roger FitzOsborne, Earl of Herefordshire.

William FitzOsborne had died in 1071, and had been King William's most trusted right hand man. The King would have taken the wardship of FitzOsborne's unmarried daughters, and so his permission was necessary before a wedding could take place. While the Anglo Saxon Chronicle says that permission was given, the Chronicle of John of Worcester says that Earl Roger gave his sister away in contravention of the King's orders. Likewise the ASC says the wedding occurred at Norwich, while John places it at Exning.

Exning was a good location to hold a wedding attended by representatives from far and wide. It was the land of Edith the Fair, and many landowners and Abbeys held property nearby, and could easily attend.

Earl Ralph naturally sent an invitation to Earl Roger of Hereford, whose sister he was marrying. Also invited to the wedding to be included in the conspiracy, was Earl Waltheof of Northampton. Many other wedding guests were there to cover up the plot.

Waltheof was a son of Earl Siward of Northumbria and became Earl of Huntingdon and Earl of Northumberland about 1065. After the Battle of Hastings he submitted to William the Conqueror; but when Sweyn II of Denmark invaded Northern England in 1069 he joined him with Edgar Ætheling and took part in the attack on York, only, however, to make a fresh submission after their departure in 1070. Then, restored to his earldom, he married William's niece, Judith, and in 1072 was appointed Earl of Northampton. By now he was the only surviving Anglo-Saxon Earl, but must have already been under suspicion by the King. He was better known for his physical strength than for his strength of will.

The three earls discussed rebellion, but Waltheof was unsure, and later he betrayed the plot to Lanfranc. Lanfranc tried to warn off Earl Roger, and sent Waltheof to Normandy to tell King William. But both Roger and Ralph raised armies to march on London, Roger at Hereford, and Ralph at Norwich.

Lanfranc sent Wulfstan, Bishop of Worcester, and the Abbot of Evesham and Walter de Lacy to head off Roger's force at the River Severn. By the time Earl Ralph and his force had reached Cambridgeshire, he was met by Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, and Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutance and their armies. There was a battle at a place called Fayeduna or Fagedun, or Whaddon in South Cambridgeshire.

Earl Ralph lost the battle at Whaddon, and fled back towards Norwich Castle with the rest of his men. It may be that he could not get to Norwich before the forces of William de Warenne, Robert Malet or Richard Fitzgilbert cut him off. He may have taken refuge in his castle at Thetford, a mound still visible in the town today. In any event the forces of these men now besieged Norwich Castle, probably led by William de Warrene.

Somehow Earl Ralph fled the country to Brittany, leaving his wife besieged in Norwich.

Earl Ralph's new wife, Emma, seems to have held Norwich castle for him against King William while he led East Anglia into rebellion.

It seems that Norwich castle held out for three months until Lady Emma surrendered. This was one of the longest sieges recorded at this time. Eventually she was given terms which allowed her and her garrison to flee abroad to be with her husband.

The king installed his own force of over 300 men in Norwich castle and Earl Ralph's lands were given to Count Alan of Brittany.

Along with William de Warrene, one man prominent in defeating Earl Ralph's rebellion was Richard Fitzgilbert, son of Count Gilbert de Brionne. He ended up with 170 English lordships, 95 in Suffolk. He made Clare his headquarters and his lands became known as the Honour of Clare. He would have been called Richard Fitzgilbert at first and possibly de Clare later. Certainly the family was using the name de Clare by 1120.

Another Norman, Roger Bigod, got 117 manors in Suffolk,and was made Earl after Ralph Wader. He also took charge of Norwich castle.

Robert Malet, son of William Malet ended up with 221 holdings in Suffolk based in Eye, where his father had quickly built a castle, the only one to be specifically mentioned in the Domesday Book for Suffolk.

These families had all participated in the earlier suppression of Hereward's revolt at Ely, and profited by it, but there was another large scale transfer of lands in Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex in the aftermath of the Earls' Rebellion.

|

|

1076

|

Earl Waltheof paid for his involvement in the Rebellion of the Three Earls in 1076. Having betrayed the rebellion to the King, he was returning to England with King William, when he was arrested. After being brought twice before the king's court he was sentenced to death. On the 31st of May 1076 he was beheaded on St. Giles's Hill, near Winchester. This is said to be the first be-heading of its type in England.

In 1070 Waltheof had married the King’s niece Judith and became the Earl of Northumberland in 1072.

At his execution in Winchester in 1076 it is recorded that “before the Earl had completed the Lord’s Prayer his head was cut from his body in a public execution. The final words of the prayer were said to have been uttered by his disconnected head.” Devout and charitable, he came to be regarded by the English as a martyr, and miracles were later said to have been worked at his tomb at Crowland Abbey in the Fens.

His wife Judith inherited Waltheof’s estates, but the land in Barnack that he had previously given to Crowland Abbey in 1061 was confiscated by King William, and given to Bury St. Edmunds Abbey. This may well have included rights to quarry the famous Barnack stone, which was the perfect medium for the Norman building ambition.

|

|

1078

|

King William began building the magnificent White Tower in London. This stone keep was the beginning of the Tower of London, still standing today.

|

|

1080

|

It is believed that from about 1075 to 1080, King William had a castle built at Colchester over the site of the old Roman temple to Claudius.

By this time the castle at Norwich was in the custodianship of Roger Bigod.

|

|

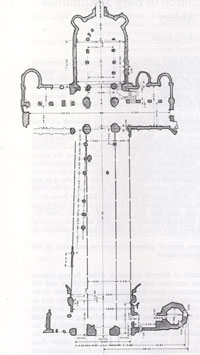

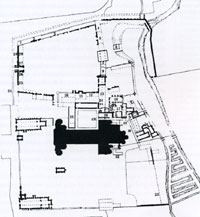

Baldwin's new Abbey Church |

|

1081

|

By this time, the Bishop of East Anglia, Herfast was increasingly aware that the Abbot of St Edmunds had more income, power and prestige than he did. He had tried to set up his headquarters at Hoxne on the northern boundary of the Liberty of St Edmund, justifying this by claiming it to be the site of St Edmund's martyrdom. The Abbot of St Edmunds objected to this.

The King again had to stop Bishop Erfast from trying to move in on the abbey at Bury. So in 1081, William the Conqueror confirmed the freedom of the abbey of St Edmund from episcopal control. On 31st May he issued a grant of privileges to "Edmund, the Glorious King and Martyr." According to a copy reproduced in Yates's History, the Bishop's case "was altogether destitute of writings and proofs". Baldwin had produced charters from Canute and Edward in support of the claim to be free of "dominion of all Bishops of that county". William also confirmed all the charters, or precepta, of earlier Kings that "this church, and the town in which this church stands, should be free, through all ages, from the jurisdiction of Bishop Arfast, and of all succeeding Bishops."

Abbot Baldwin had successfully fought off the Bishop, and in the course of the dispute, he obtained exemption from episcopal jurisdiction, not just for the abbey, but also for the town of Bury itself. This resulted in the abbey sacrist being responsible for appointing the parochial chaplains and taking any tithes due to the churches of St James and St Mary. In practice the sacrist was the parson of both parishes, carrying out duties normally undertaken by an archdeacon of the diocese.

This ended the attempts by Bishop Erfast to turn Bury into the cathedral of his see.

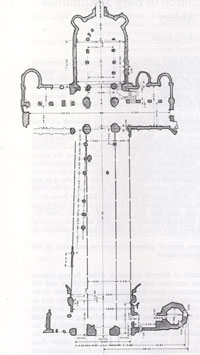

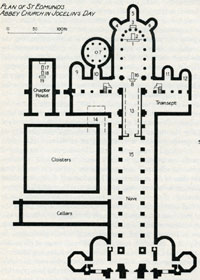

This event probably helped to kick-start work on a great new Abbey church at Bury, supported by the Conqueror. Norman sensibilities demanded stone buildings of a size and style unknown to Saxon England before 1066. The separate chapels and churches and haphazard buildings had got to be sorted out and replaced to glorify the new order. The King advised Baldwin to build a new and magnificent church. The establishment of the monastery was also increased from twenty to forty according to Professor Eric Fernie.

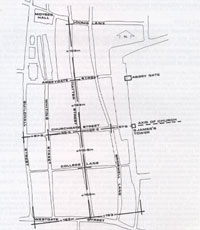

So, from about this time, Abbot Baldwin and the Sacrist Thurston probably began to organise the first great re-building of St Edmund's abbey church. The old saxon town had probably been centred inside what today we would think of as the Abbey precincts, but at the time was probably thought of as a normal mix of church and commerce and residential. The Normans liked tidy streets in an orderly grid pattern, just as they had done in Normandy since the plan for Rouen was set in the early 10th century, followed by other similar plans in that Dukedom.

|

|

Layout of St Edmund's proposed new town |

|

blank |

Now land which had been under the plough was laid out in a grid and Baldwin's new streets probably included families pushed out of the abbey precincts by its expansion. It was also a process of separating the religious establishment more clearly from the townspeople.

Eric Fernie has suggested that the plan for the new Abbey church was laid out using the proportion of one to the square root of two. He further suggested that this ratio was carried forward into the layout of the new grid pattern of streets.

It is not clear whether the Saxon Road directly linking Northgate Street to Southgate Street was fully deflected to the present configuration around the abbey precincts at this time, or not until Anselm's day. That part of Northgate Street from Pump Lane to Angel seems to have been called High Street in early days, which might echo the idea of it being the old main street running straight on through today's Abbey Gardens. Angel Hill itself was called The Mustowe until the seventeenth century, meaning a meeting place, and could have been Anselm's market place. The new abbey boundary was probably moated by Baldwin to give a more formal separation of abbey and town.

|

|

1084

|

In 1084, Herfast, Bishop of East Anglia, based at Thetford, died. He had amassed many estates and manors in his time since appointment in 1070, and helped to give Thetford a boost. He was succeeded by Bishop William de Beaufeu, also known as William Galfragus or Galsafus.

An exceptionally heavy geld was collected to help the King pay for a large army of foreign mercenaries to defend the realm against the Danes.

|

|

1085

|

The great army raised against threat of a Danish invasion was billeted on English landholders, "each according to his land". Tax gathering and billeting proved that valuations were out of date and there were disputes over land claims and exemptions. Action was needed to sort out these problems. While holding court at Gloucester the King decided to carry out a survey of the wealth of his new Kingdom. Officers were sent to all parts of the country to compile an inquest or survey of property, later known as the Domesday Book, which is still to be seen in the Public Records Office in London.

|

|

Click for more on Domesday

|

|

1086

|

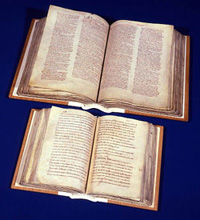

The survey upon which the Domesday Book was based took place in 1086 and remains a valuable source of information about this period. The surviving Domesday Book probably took another couple of years to compile from the surveyors notes. One idea is that the surveys of Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex were never properly compiled in this way, and the notes were just copied in their raw form into a separate volume which came to be called the Little Domesday Book. Another possibility supported by Dr Lucy Marten is that, on the contrary, perhaps Norfolk , Suffolk and Essex were completed first. These were the most prosperous areas, and the most important to survey. Perhaps the production of them as the first volume took so long to produce that the rest of the country was done using a much more abbreviated and standardised form.

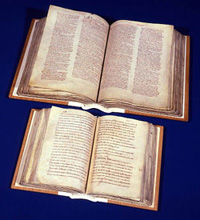

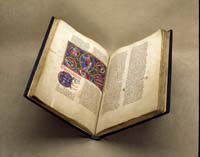

You can find more about this survey by clicking on the illustration adjacent to this text.

By 1086 the Little Domesday tells us that the Abbey of St Edmund's owned estates, chiefly in Suffolk, but stretching through several counties. Under Norman rule these properties of the Abbey were referred to as the Barony of St Edmund whereas the Liberty was the area of jurisdiction covering West Suffolk. Like all property owners, William the Conqueror required the Abbot to provide a certain number of knights for the Kings Army. This baronial obligation brought the Abbot into the royal circle, to be consulted on matters of state. If an Abbot died the Barony passed into Royal custody until a successor was elected. The feudal quota due from St Edmund's Barony was forty knights. Like other Barons, the Abbot installed tenants on the estate and in return for their property rights (their fees) they were obliged to perform this knight's-service, usually of forty days duty at their own expense. This could be on active service or later by guard duty at Norwich Castle. Although the Abbot owed the King 40 knights, he had let 50 fees by the time of Samson, hoping to keep the 10 for himself as Abbot.

This military service could be avoided by payment of scutage money.

Many of the best manors were not let as Knights' fees but directly run by the Abbot and were called demesne manors. Many of these Manors were held by the Abbey since before 1066, and these are identified in the Domesday Book. Although the Abbot was deprived of Mildenhall by 1086, one of his most prosperous holdings, others, like Chevington and Saxham were acquired by Abbot Baldwin since the Conquest. Chevington, formerly owned by Britulf, was given to the Abbey by William I. Future abbots would have an important Hall here, and Chevington Hall Farm survives on this site.

You can see maps of the Abbey holdings, both in 1066 and by 1086, by clicking here:

Maps of Abbey Landholdings 1066 and 1086

At St Edmund's Bury town itself the Domesday book recorded 500 dwellings, and many of the inhabitants depended on the monastery for a living. Some 75 bakers, ale brewers, tailors, washerwomen, shoe and robe makers, cooks, porter and purveyors "daily wait upon the Saint, the Abbot, and the Brethren." The Domesday Book recorded 30 priests, deacons and clergymen in Bury together with 28 nuns and poor people who "daily utter prayers for the King and all Christian people". Bury's population might have grown to 2,250 by 1086. The town was now valued at £20, or twice its value in 1066.

Dr Lucy Marten has pointed out that the entry for Bury is quite unlike other entries. It rambles on about "praying for the king", and lists all the traders etc., and she suggests that the entry was written, not by the Commissioners, but by the monks themselves, or even directly by Abbot Baldwin.

|

|

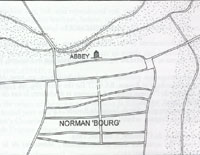

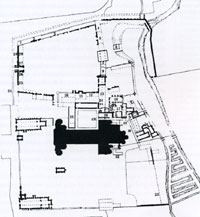

Bury 1086 by Bernard Gauthiez |

|

blank |

Baldwin was Abbot of St Edmunds from 1065 to 1097 and Domesday credited him with building 342 houses by 1086 on land which used to be under the plough. The relevant extract is as follows, taken from the Phillimore translation:

"14, ('Lands of St Edmund')

167

In the town where St Edmund the glorious King and Martyr lies buried, ........................

Now 2 mills; 2 ponds or fish ponds.

Value of this town then £10; now £20.

It has 1½ leagues in length and as much in width.

When the Hundred pays £1 in tax, then 60d goes from here for the monks' supplies;

but this is from the town as it was before 1066 and yet it is the same now although it is enclosed in a larger circuit of land which then was ploughed and sown but where now there are 30 priests, deacons and clerics, and 28 nuns and poor persons, who pray daily for the King and all Christian people.

Also 75 bakers, brewers, tailors, washers, shoemakers, robemakers, cooks, porters, bursars; all these daily serve St Edmund's, the Abbot and the brethren.

Besides these, there are 13 reeves in charge of the land who have their houses in the same town;

Alternative translation by Domesdaytextbase: "Besides these, there are 13 [men] on the reeve's land

who have their houses in the same town;"

under them, 5 smallholders.

Also now 34 men-at-arms, including French and English; under them, 22 smallholders.

Now in all there are 342 houses in lordship on land which was St Edmund's arable before 1066."

This building was probably arranged in five new streets to the west of the Abbey, running north to south in a grid plan, still clearly visible today. These houses generated rents and the market generated tolls and fees for the Abbey. The convent held 400 acres of arable land within the Banleuca, or the town boundary which lasted up to the 1930's. Nothing could be built in the Banleuca without the permission of the Abbot and the Convent. The town was recorded at 2.5 miles long and the same length wide.

However, the town ditch enclosed a tighter, urban area with its South, North, East, West and Risby gates. The people living inside the ditch enjoyed more privileges than the suburban dwellers in the Banleuca outside. The town ditch was probably not replaced by a wall until about 1136.

The Sacrist of the Abbey controlled the borough court and appointed the town reeves or bailiffs, administering justice and running a gaol right up to 1539.

The main Borough Court at this time was the portman-moot, which administered the borough's old customs. The burgesses were exempt from going to either the Shire Court or to the Hundred Court. The portman-moot pre dated the local monastery's rise to power, and as years passed, its influence was to wane as the abbot's power grew.

The first mention of Haverhill proper occurs in 1086, when the Normans carried out their famous Domesday survey. They recorded that a market was operating and as only eleven such markets are recorded for Suffolk, it would appear that Haverhill was of considerable importance. The local Norman lord of the manor was Tihell de Helion, although to call him a Norman may not be strictly true, as, in fact, he came from Brittany and took his name from his native village. The Domesday Book recorded that he owned one third of the market, the remainder being given to the Gilberts of Clare. The Saxon Clarenbold was dispossessed in 1066. The market was valued at 13s 4d and was situated at Burton End.

At Clare, the "comes famoses" (or renowned magnate) Aelfric had been an important Saxon thegn, owning estates in Suffolk and Essex. Domesday recorded that Aelfric had given the substantial 24 carucate (2880 acres) manor of Clare to the religious house of St John before 1066. He had placed therein a certain Ledmer the priest and others with him. When a charter had been made, he committed the Church and the whole place to the custody of Abbot Leofstan and into the protection of his son Withgar. The clerics could not grant this land or alienate it from St John's. But after King William came, he took possession of it into his own hand.

It is not clear why the manor was confiscated from St John's, or exactly when, but by 1086 it was in the hands of Count Gilbert, then passing to his son. Also by this time it was endowed with 5 arpents of vineyards, and 12 beehives, speaking of a high status vill, suitable for an abbot or a major Norman lord.

The religious foundation of St John's seems to have survived this loss of its wealth by way of the patronage of Count Gilbert himself. Their church was incorporated within the castle grounds, but their religious life was placed into the hands of the Monastery at Bec, in Normandy, in France. This act would have established St John's as a Benedictine order, if it were not so already. Gilbert himself now endowed the church with a number of his newly acquired assets in Norfolk and Suffolk, and the pastures of Horscroft and Waltuna in Clare.

Count Gilbert's son, Richard FitzGilbert, would build his own castle at Clare to demonstrate to the Saxons that all their old duties and dues would now be payable to him as the new Lord. By about 1120 the family were using the name de Clare.

|

|

Hundon Parks |

|

blank |

Part of FitzGilbert's landholdings included Hundon, and although not mentioned in Domesday, we know that by 1090 the Stoke by Clare cartulary was referring to deer for the sick monks being taken from FitzGilbert's parks there. In fact, FitzGilbert had three adjacent, but separate, parks in Hundon. To the west was Broxtead Park, to the east was Easty Park, and between them stood Hundon Great Park, as large as the other two put together. Each park had its own central lodge. These were areas on the high boulder clay soils, which were less suitable for farming using the methods available at the time. They were cold and ill drained, and had been left as forest by the Saxons. Under Aelfric these parks may have been more or less open, but were probably used by him for the sport of hunting, just as the Norman FitzGilbert would continue. Under the FitzGilberts the land probably became more closely defined and enclosed by banks, ditches and hedges.

The Normans were responsible for introducing two new animal species to the British record. These were the fallow deer and the rabbit. Having set up his parks, FitzGilbert was part of this introduction so far as the fallow deer was concerned. They were kept within his own enclosures for hunting by himself and those honoured guests whom he wished to impress. Rabbits were prized for both meat and fur, but the cold clay soil conditions at Hundon were probably unsuitable for the rearing of rabbits here at this time.

The village of Woolpit is recorded in the Domesday record, spelled Wlfpeta, or Wolf Pit. The use of baited pits to trap wolves was the usual method of destroying the wolf, which was regarded as a frightening predator. Wolves survived in England until about 1550, but in the more populated areas like East Anglia, it was probably more or less eradicated by 1086.

It is interesting that the only castle in Suffolk actually mentioned in the Domesday Book was at Eye. Here, Robert Malet had been granted the lands of the Saxon lord, Eadric of Laxfield. Malet set up his home estate here, and his holdings became known as the Honour of Eye. Malet was landlord number 6 in the Domesday Book for Suffolk, and his lands took 27 pages to record. However, this reference to his castle does not appear under Malet's own record at Eye, which is 6,191; but under section 18,1 part of the lands of William, the Bishop of Thetford. Under the heading for the Bishop's manor at Hoxne, the Domesday Book noted that Hoxne had had a market on Saturdays since before 1066, as follows: "W Malet made his castle at Eye and, on the same day that there was a market on the Bishop's manor, W Malet established another market in his castle. Because of this, the Bishop's market declined so that it is worth little; and it now takes place on Fridays. However, the market at Eye takes place on Saturdays."

Eye itself consisted of 12 carucates, where one carucate was equal to 120 acres, and so was a large holding in its own right. The Honour itself included many other estates such as Rishangles, Brundish, Dennington and Leiston. By 1086 there was also one Park recorded within the estate of Eye.

At Thetford the survey showed that it was divided between King William and Roger Bigod, and they may both have begun to build castles there.

In England as a whole, the Domesday Book showed that by 1086 20 per cent of the land was owned by the King, 25 per cent by the Church, 50 per cent by Norman Barons, and only 5 per cent by Anglo-Saxons. Suffolk itself had 2,400 land holdings, apparently one of the wealthiest and most densely settled counties of late Saxon and early Norman England, averaging 10 to 12 households per square mile.

In 20 years the locals had been dispossessed, and with French now the official language, the thriving Anglo-Saxon culture of pre-1066 suffered badly.

The scholarly Norman Lanfranc had been made Archbishop of Canterbury and the Church hierarchy had been Normanised thoroughly with his help.

Anglo Saxon Earls were replaced by Norman Barons, and a new hierarchy was set up below the King with land tenure based on military service. It was a society based upon the pursuit of war.

In 1066 Ipswich had been the largest town in Suffolk. By 1086 Ipswich had suffered severe depopulation and destruction, as it was implicated in resistance to King William. Norwich also suffered in the same way. By contrast, Bury St Edmunds and Dunwich had flourished under Norman rule. Dunwich had been promoted as a port to rival Ipswich, and would continue to flourish until natural disasters eventually destroyed both port and town.

Some estimated population figures for 1086 are as follows:

- London - 15,000

- York - 8,500

- Winchester - 8,000

- Norwich - 6,500

- Lincoln - 6,000

- Thetford - 5,000

- Dunwich - 3,000

- Ipswich - 2,500

- Cambridge - 2,250

- Bury St Edmunds - 1,500

Beccles, Clare, Eye and Sudbury were smaller important centres in Suffolk, and were credited with burgesses in the Domesday Book. Burgesses were free to pursue trade and industry without the obligations of manorial and agricultural life.

|

|

1087

|

King William I died in Normandy after a year of fighting rebellions there, including his eldest son Robert Curthose. He was succeeded by Robert's brother William, known as William Rufus, or King William II, who ruled until 1100.

|

|

1088

|

The King's brother Robert, supported by many Barons, was in rebellion. They seized land, and at Norwich the locals rose up to attack Roger Bigod in the great keep. They succeeded in expelling him.

Following such seizures the Domesday survey became needed to sort out those possessions that the King wanted back. William II therefore either encouraged completion of the great book or in the view of one historian, actually caused the survey to be written up into the Domesday Book.

In 1088 William de Warrene died. He seems to have been holding Thetford Castle at this time, and on his death it reverted to the crown.

|

|

1089

|

At some point, possibly between 1087 and 1098, Abbot Baldwin produced his own Feudal Book. Like the Domesday Book, it listed all the property that the Abbot considered belonged to him and the Monastery of St Edmund. It has been transcribed by Professor D C Douglas and published in his 1932 work entitled, "Feudal Documents from the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds." It was substantially reproduced in the Pinchbeck Register, a list of the abbey's privileges produced much later, in the 14th century.

Professor Douglas decided that the Abbot's book was not just a copy of Domesday, but relied upon other supplementary information, not included in the Domesday Book. The introduction states that it was intended to state the landholding position at the time when William I made his description of all England; ie Domesday Book.

The first section of his book is laid out like the Domesday Book. It lists holdings under each Hundred, and then under each vill. The second section proceeds tenant by tenant. The third section which survives covers only Thedwestry, Blackbourn and Cosford, where entries are vill by vill again, but lists all the tenants with a summary of their holdings and amounts due. The other Hundreds appear to be missing or lost.

|

|

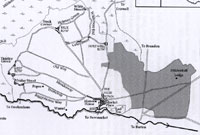

Fenland waterways 1604 redrawn by M Chisholm

|

|

1090

|

By 1090 work had begun on the great new church for the abbey of St Edmund. Most of the stone was to come by river boat from Barnack quarries near Peterborough.

In his Opera Posthuma of 1745, "Antiquitates S Edmundi Burgi", John Battely, the late Archdeacon of Canterbury, discussed the shipment of stone from Barnack, and referred to a an order to Peterborough, issued by William the Conqueror, that Abbot Baldwin of Bury, be permitted to have as much stone as needed for the monastic church 'as he has had up till now and not to make any further hindrance for him in bringing stone to the water which you have formerly done.' Batteley refers to Gunwade as being the location where the stone was loaded on to boats on the River Nene. Professor M Chisholm argues that it would have been cheaper to load stone at Pilsgate on the River Welland and take the 9 mile longer river route, via the Crowland Cut, but obviating the shorter, but much more expensive 4 mile land route to Gunwade.

Barnack,Gunwade and Pilsgate are all visible on the attached map by M Chisholm, published in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, 2010 and 2011. Click on the thumbnail for a larger version. Chisholm suggests that both routes may have been used at different times.

According to John Lydgate writing in 1430 some stone came from Caen in Normandy by sea and landed on the strand at Rattlesden. If this ever was the case, it may have happened two centuries later when Barnack quarries were becoming exhausted. Baldwin built St Denis's church for use by the town on the site of the chancel of the present cathedral. This was to compensate them for losing the right to worship in the abbey church.

|

|

1091

|

The second Bishop of Thetford, William de Beaufoy died. In the Domesday book his bishopric was shown to own more than 70 manors. He was succeeded by Bishop Herbert de Losinga.