Round House at West Harling

Quick links on this page

Celtic arrivals 400 BC

Iceni and Trinovantes 100 BC

Julius Caesar's expedition 54 BC

Cunobelin 10 AD

Roman invasion 43 AD

Boudicca's revolt 59 AD

Six Roman towns 100 AD

Antonine Itinerary 210 AD

The Saxon Shore 270 AD

Stanton Chair 300 AD

Christianity Official 312 AD

Late Roman period 350 AD

Mildenhall Treasure 360 AD

Thetford Treasure 390 AD

Hoxne Treasure 409 AD

Bottom of Page 410 AD

|

The Iron Age

and the

Roman Empire

700 BC to 410 AD

Pre

700 BC

|

Please click here if you wish to look back at events in the Bronze Age and before.

|

|

700 BC

|

Iron was introduced to Britain in about 800 to 700 BC and as its use would slowly spread, the use of bronze for tools would decline but continue for bowls and ornaments etc.. However, the way of life of the Bronze Age inhabitants did not change overnight. Iron had been in evidence on the continent and in central Europe for at least 300 years already. The continental Iron Age of this time is usually referred to as Hallstatt phase C, and this cultural influence accompanied the spread of iron working knowledge into Britain.

In our area, the people were still living in settlements in the north west of Suffolk on the light, well drained soils of Breckland. It has been thought that raiders from Belgium left sword scabbards found at Lakenheath. Nowadays, such evidence is much less readily attributed to invaders and more readily linked to trade or cultural exchange. Unfortunately nearly all of the iron objects have rusted away fairly quickly, and so the Iron Age is perhaps less evident in the ground than the Bronze Age. Nevertheless we are fairly sure that iron artefacts would not come into general widespread use until after 500 BC to 400 BC.

|

|

650 BC

|

In Norfolk the earliest iron age phase is called after a site at West Harling, Micklemoor Hill. A circular bank and shallow ditch with two causeways have been identified. The round house is the typical building thought to mark out the iron age, although rectangular features have been noted at places like Rickinghall Inferior. The West Harling site is on a knoll close to the River Thet. Because of the size of the round house here, it is thought that the roof did not cover the whole structure, but a central yard was left open.

West Harling people herded oxen and sheep, cultivated wheat and hunted wild pig, red deer, the crane and the beaver. Remains of 530 pots were found.

At some point during the Iron Age, the Brown hare was introduced into England. It does not occur in the archaeological record before this time, but it is still a feature of East Anglian fields today.

|

|

Bronze sword 600BC

|

|

600 BC

|

Although the Iron Age had begun, bronze was still in use for fine objects of desire. This bronze sword dates from about 600 BC. A bronze weapon was just as powerful as an iron weapon around 700 BC. It did not rust, and held an edge just as well. They were light, at around 800 grams, and until iron working improved they were still formidable weapons.

This period from 600 BC to 500 BC is referred to as Hallstat D, when iron daggers appeared in graves on the continent.

|

|

500 BC

|

The Iron Age had begun in Britain, but Bronze continued to be worked. It is thought that the few bronze arrowheads ever found date from this time. They were mostly made on the continent and only a very few tri-lobe bronze arrow heads have ever been found in Britain.

|

|

450 BC

|

By about 450 BC, a new artistic tradition was on the rise within the continental Celtic world. This artistic culture is typified by excavated remains from a site called Le Tene located on the edge of a lake in Switzerland. This was a development in one small part of the Hallstatt sphere of influence. Elaborate and artistic treasures were found here, and notable artefacts from this culture would begin to appear in Britain.

Not until this period would iron objects move from the sphere of scarce luxury item, into more general widespread utilitarian usage.

This description of early ironworking comes from Wikipedia:

"Iron smelting at this time was based on the bloomery, a furnace where bellows were used to force air through a pile of iron ore and burning charcoal. The carbon monoxide produced by the charcoal reduced the iron oxides to metallic iron, but the bloomery was not hot enough to melt the iron. Instead, the iron collected in the bottom of the furnace as a spongy mass, or bloom, whose pores were filled with ash and slag. The bloom then had to be reheated to soften the iron and melt the slag, and then repeatedly beaten and folded to force the molten slag out of it. The result of this time-consuming and laborious process was wrought iron, a malleable but fairly soft alloy containing little carbon."

|

|

400 BC

|

Some of the Celtic speaking peoples now seem to have entered Britain from the Low Countries and iron tools allow agriculture to spread to less light soils. The Celts were looked on by the Romans as one of the many tribes living in Europe in the years before Christ. But they are better seen as a linguistic group, made up of many different customs and traditions, but sharing a common language form. About 400 BC they began to leave Central Europe, possibly because of harassment from other tribes. The Celts from Northern France and the Netherlands crossed the Channel and settled in England. They were known as the Brythons, from which we derive the name Britons.

The Celtic language is now divided into two types, mainly depending upon the use of a "p" sound or a "q" sound in certain key words. The Brythonic type is known as P-Celtic, and was spoken all across mainland Britain. It survived in the languages of Welsh, Cornish, Cumbric and Pictish.

The Goidelic type of Celtic is known as Q-Celtic, and at this time it was the language of the land now called Ireland. Eventually an Irish tribe called the Scottii would carry Goidelic into Scotland as well, but this would not occur until the Roman period and after.

|

|

320 BC

|

As early as 320 BC the Greek navigator and geographer, Pytheas of Massilia, (modern Marseilles), seems to have carried out a partial exploration of the island of Britain, known to him as Albion. He eventually reached Belerium (Land’s End, Cornwall), where he visited the tin mines, famous in the ancient world. He found the British to be skilled in growing wheat. His comments on small points included reference to the native drinks made of cereals and honey and the use of threshing barns (contrasted with open-air threshing in Mediterranean regions).

Diodorus based on Pytheas, reported that Britain is cold and subject to frosts. This report suggests that Pytheas was there in the early Spring, as he encountered frosts but not blizzards, snowdrifts or ice.

The numerous population of natives, he says, live in thatched cottages, store their grain in subterranean caches and bake bread from it. They are "of simple manners" and are content with plain fare. They are ruled by many kings and princes who live in peace with each other. Their troops fight from chariots, as did the Greeks in the Trojan War. Until Caesar they were never beaten and never invaded.

|

|

Typical hand made cooking pots

|

|

300 BC

|

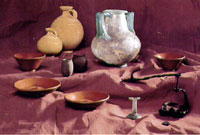

These hand made cooking pots were produced over many centuries, and their nature would not change much from the 3rd to the 1st century BC. However, by about 50 BC they would become superceded by wheel made pots, when the potter's wheel was introduced from the continent.

|

|

Iron bladed Dagger

|

|

200 BC

|

Gold staters from Gaul began to reach Britain. A stater is the name given to the standard Celtic gold coin.

By comparison, in Sicily in 212 BC, one of the greatest mathematicians the world has ever known, called Archimedes, was killed when the Romans invaded the city of Syracuse. This city had been part of Greater Greece, a mighty Mediterranean Empire, renowned for its culture and learning. It would be eclipsed by the military might of the Romans, who would set up their own empire, based on their technological innovations in a whole range of activities, not least of which was military arms and tactics.

|

|

150 BC

|

A succession of coins manufactured by the tribes of Northern France was imported into south-east England beginning around this time for at least a hundred years. This area of France has been called Belgica, and these coins are known to collectors as Gallo-Belgic A to F series. In the past this evidence was thought to indicate successive waves of Belgic invaders, but this is no longer widely believed. Although Caesar recorded Belgic raiders to England who may have settled there, it is now thought to indicate payments for military service, close cultural links and trading ties as well as gifts cementing political or social alliances across the Channel.

|

|

Two tribes meet in Suffolk

|

|

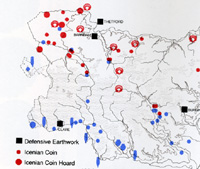

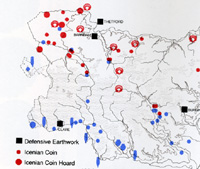

100 BC

|

It is thought that there were two separate peoples in Suffolk at this period, with a boundary roughly from Newmarket to Stowmarket and Aldburgh. To the north were the Iceni, and in the south the Trinovantes. Their names are known from Roman writers. The iron age Iceni tribal heartlands were in North West Suffolk around Ixworth and the Blackbourne Valley and Icklingham, West Stow and the Lark Valley. They extended into South West Norfolk and north and south along the Icknield Way. The Iceni were widespread in Norfolk and archaeological remains there confirm the Roman descriptions of them using wheeled chariots drawn by a pair of ponies in warfare.

|

|

Iron Age earthworks at Thetford |

|

blank |

In Norfolk the Iceni had an earthwork fort at Warham Camp, near Norfolk's north coast. It was bigger than any fort in Suffolk. They also had a major fort with earthworks which survive today at Thetford. This fort would be re-used by Viking invaders in the 9th century, and most notably by the Normans, who added the massive central mound, or motte, in the 11th century.

Most of their remains in Suffolk are from Cavenham to Thetford. These people kept cattle and water had to be available within a mile of the herds, a requirement which held true up to the 20th century.

|

|

Iron Age cropmarks at Barnham |

|

blank |

An Iceni iron age fort has been identified at Barnham surrounded by ditches and ramparts. Measuring 105 by 77 yards, it is rated as a small fort by iron age standards. The ditches were 23 feet wide and 10 feet deep, and the ditches were built between 180 BC and 20 AD. This aerial view shows the dark cropmark of a double-ditched trapezoidal enclosure. A small excavation in 1978 showed that it dates from around 100 BC and may have had a religious rather than a military function

In South Suffolk the people were known as Trinovantes and are also known as the Belgic or Belgae tribes and were supposedly later arrivals from the Continent.

|

|

Erbury Camp at Clare |

|

blank |

In South Suffolk, an earthwork called Clare Camp seems to have been an iron age fort of this tribe. In Saxon times it was called Erbury, and Erbury Manor was located here. It was surveyed in 1993 and categorised as a probable iron-age bi-vallate enclosure. It is the largest earthwork in Suffolk, enclosing a square area of about seven acres. The two banks are still up to nine feet high, with double ditches on their outer sides. These people also had a settlement at Long Melford and this Stour Valley group looked to Camulodunum as their capital next to where Roman Colchester arose.

|

|

Iron Age enclosure at Burgh |

|

blank |

In East Suffolk there is well established evidence of a ditch and rampart fort around the churchyard at Burgh. It measured 300 yards by 225 yards, and may be associated with the Trinovanti tribe. In any case it may well have been on the borders between Trinovanti and Iceni. This enclosure is hardly visible on the ground, and appears to surround a small valley, which now houses a lane. However, it has been excavated over a number of years by several teams, and there is evidence of occupation right from the Iron Age through the Roman period. Later it was to form the setting for the local church. The latest excavations were written up by Edward Martin in East Anglian Archaeology Report number EAA 40 of 1988.

This was an organised society able to produce luxury goods such as the six famous gold torcs found at Ipswich in 1968-70, weighing 2lbs each.

Celtic names today only remain in isolated places. Most are found in Wales and Cornwall where the Celtic tongue held out, long after other areas accepted the language of the Anglo-Saxons. Very few names in Suffolk contain Celtic elements. Walsham (le Willows) means 'home' of the 'Welsh' ie the British. Walpole comes from Old English for The Britons' pool and Walton means The Britons' farmstead. Dunwich may derive from the Celtic words for Deep Water Port.

Perhaps the oldest British made coins were not made of gold, but were a series of cast bronze or "potin" issues manufactured in Kent. These appear to be based on the bronze coinage of the Greek Colony in Marseilles (Massalia). A hoard of this bronze coinage was found in Thurrock in Essex, and samples have been found in East Anglia.

|

|

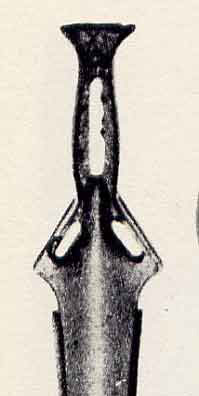

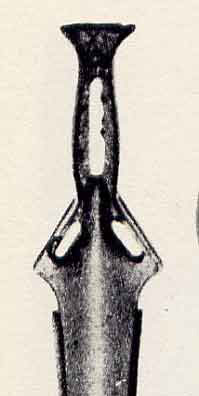

Snettisham Great Torc

|

|

75 BC

|

The illustration is of the best of a number of gold torcs found near Snettisham in Norfolk, in the heartlands of the tribe which we know as the Iceni. What caused these valuable and beautiful objects to be placed in the ground is unknown.

One torc in particular has been called the Great Torc, and the British Museum calls it the most famous object from Iron Age Britain.

The great torc was found when the field at Ken Hill, Snettisham was ploughed in 1950. Other hoards were found in the same field in 1948 and 1990. The torc was buried tied together with a complete bracelet by another torc. A coin found caught in the ropes of the Great Torc suggests the hoard was buried around 75 BC.

The British Museum description of the Great Torc is as follows:

"This torc was made with great skill and tremendous care in the first half of the first century BC. It is one of the most elaborate golden objects made in the ancient world. Not even Greek, Roman or Chinese gold workers living 2000 years ago made objects of this complexity.

The torc is made from just over a kilogram of gold mixed with silver. It is made from sixty-four threads. Each thread was 1.9 mm wide. Eight threads were twisted together at a time to make 8 separate ropes of metal. These were then twisted around each other to make the final torc. The ends of the torc were cast in moulds. The hollow ends were then welded onto the ropes."

|

|

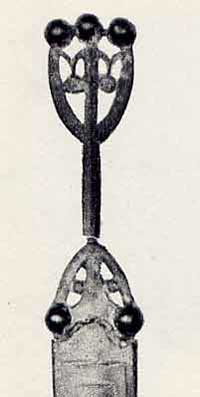

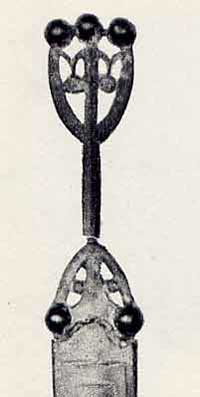

Ipswich Torcs |

|

blank |

Dating from the same period, but found in the Trinovante lands near Ipswich, were these torcs. Five of these gold torcs were found during construction work near Ipswich in 1968. The sixth was found nearby about a year later.

Scientific analysis at The British Museum shows that the torcs are made from an alloy of 90% gold and 10% silver. Gold objects made from between 150 and 75 BC have a high percentage of gold. Gold objects made after 75 BC have more and more silver mixed with the metal. The scientific results suggest this set of torcs were made around 75 BC. Highly valuable objects like these might have been worn for many years before they were buried.

The British Museum description is:

"Each torc was made by twisting two rods of gold around each other. The ends, the 'terminals', were each cast on to the twisted rods using the lost wax technique. Each terminal is hollow, the La Tène-style decoration cut into the clay mould so that it stands up from the surface of the ends, which were then polished. Each terminal, of all the torcs, has a slightly different pattern from its pair. "

|

|

70 BC

|

British made coinage was circulating by this time, much of it apparently copied from Roman designs. British coins started to be produced in gold and are sometimes called British A to P. At the same time there were also quarter staters, silver units and bronze units produced.

|

|

65 BC

|

A coin known as British G has also been called the Clacton type because a hoard was discovered at Clacton in 1898. Activities by metal-detectorists in the 1990's have since discovered more of them. The Clacton stater has crescent moons and laurel leaves on one side and a celtic horse design on the other. It should be noted that the Yarmouth stater was found at Yarmouth in the Isle of Wight, not in Norfolk.

|

|

60 BC

|

By this time close relationships existed between Southern Britain and Northern Gaul. The part of Gaul called Armorica had trade links with Dorset and further north there were several cross channel routes. Caesar noted that in his wars in Gaul he was often faced with British contingents and that Gallic fugitives would often escape to Britain. This may have led him to consider a punitive expedition against the British.

|

|

Bury Diadem Iceni coin |

|

blank |

Dating from around this time is a mysterious group of Iceni coins called the Bury type or Bury Diadem type because the first examples were discovered around Bury St Edmunds. They circulated widely in Norfolk and Suffolk and may be the earliest Iceni silver coins. They feature a well-styled female head with a complex crown on one side and a well modelled horse on the reverse.

In Norfolk, the coin known as 'British J' came about when the horse motif was replaced by a wolf by the Iceni moneyers. Today this coin type is often called "Norfolk Wolf". The Iceni were to become producers of a vigorous and inventive coinage somewhat isolated from the modernising Romanised tribes further south.

|

|

Gallic Uniface coin

|

|

55 BC

|

Following a similar punitive raid across the Rhine into Germany, Julius Caesar (102-44BC) led 80 ships and 2 legions in a landing near Deal, on the Kentish coast. Caesar was Proconsul to Transalpine Gaul, and this was his first expedition to Britain. He defeated some defenders, claiming the surrender of four Kentish kings. He also claimed that the weather was against him, and he withdrew, to return in the following year.

The Roman Empire now began the conquest of Gaul. Julius Caesar wrote down his experiences in his book on the Gallic Wars, "De Bello Gallico". Many of his comments contribute to our knowledge of the time. He wrote that one of his opponents was King Diviciacus of the Suessiones in Belgic Gaul and that he previously had control over a large area of Britain. This supports the idea of close links between Britain and Belgica around this time.

From around 60 BC to 50 BC huge numbers of the coin known as Gallo-Belgic E were struck, with a stylised horse on one side and a blank obverse design. It has been estimated that about 5,000 kg of gold was needed to produce this coinage, almost certainly to pay troops to fight Caesar in Gaul. Large numbers of this coin have been found in Britain, spread from the south coast to the Humber, confirming Caesar's comment that Britain was a base for his enemies in Gaul.

|

|

54 BC

|

Having withdrawn in 55 BC, Julius Caesar led a second expedition to Britain and met fierce resistance from Cassivelaunus who had been elected by the British to lead their defence. This time Caesar had four Legions and a force of Cavalry, and his army was trained in a type of aggressive war largely alien to the defending Celtic tribes.

Eventually this invasion resulted in the surrender of the British federation of tribes. Cassivelaunus was the powerful King of the Catuvellauni, who lived north of the Thames. To replace him, Caesar installed as King of the Trinovantes a British prince whose father had been killed by Cassivelaunus and Caesar expected an annual tribute in return. The Trinovantes were centred on Colchester and covered South Suffolk, Essex and Cambridgeshire.

Peace terms were settled and Caesar took tribute and hostages, but then left. Today's historians believe that tribute continued to be paid to Rome, and its influence was to grow over the next century. Britain did not just return to some state of isolation even though no further attempts at invasion took place for 100 years. Julius Caesar was later to write that the tribes he encountered in South and East England were very similar to the peoples of Gaul.

Although Roman forces left British shores the next hundred years produced large changes in British society. The Belgic culture crossed the Channel into southern Britain along with growing Roman contacts. There was a flowering of celtic arts and an establishment of land division that has partly persisted up to today. Large settlements with earthworks were established. British Celtic coinage sometimes included Latin legends and classical designs, well before the final invasion in 43 AD.

|

|

52 BC

|

In Gaul, Commius of the Atrebates had been Caesar's Gaulish confidante, advising him in his campaigns against various Gaulish tribes. However Commius now attempted to relieve his countryman Vercingatorix during the siege of Alesia. He was defeated by the besieging Roman legions and fled to southern Britain to escape the retribution of Caesar. This shows that Gaul and Britain had close links at this time, and this helped to make Britain a target for future Roman action.

Commius seems to have founded a dynasty around Silchester in Hampshire, made up of Atrebates exiles from Roman Gaul. These were people known as the Belgic tribes.

|

|

Battersea Shield

|

|

50 BC

|

From about 50 BC there is archaeological evidence for stronger links with the continent, particularly in the south of our region. British iron age pottery noticeably improved as the potter's wheel was introduced from the continent.

The culture of La Tene in Switzerland first saw the rise of what we would today call Celtic Art. This shield dates to some time between 350 BC and 50 BC, but the later date seems most likely. This was recovered from the River Thames at Battersea Bridge, but when it was placed there, of course, there was no bridge.

This is not a complete shield. It is a beaten metal covering that would have been placed on a wooden back. It was probably for show rather than for serious fighting.

The highly polished bronze and glinting red glass would have made for a great spectacle. It was finally thrown or placed in the River Thames, where many weapons were offered as sacrifices in the Bronze Age and Iron Age.

Iron Age shields are not commonly found. Those shields excavated from Iron Age burials were made of wood, sometimes covered with leather. They have very few metal parts, unlike this example.

The British Museum description is as follows:

"All of the decoration is concentrated in the three roundels. A high domed boss in the middle of the central roundel is over where the handle was underneath. The La Tène-style decoration is made using the repoussé technique, emphasized with engraving and stippling. The overall design is highlighted with twenty-seven framed studs of red enamel (opaque red glass) in four different sizes, the largest set at the centre of the boss."

|

|

44 BC

|

Julius Caesar was assassinated by Brutus and Cassius and others in the theatre of Pompey at Rome. Civil war ensued and Britain was left alone.

|

|

40 BC

|

The Norfolk wolf coinage of the Iceni was replaced somewhere around this time by a group known as the Freckenham type (British N). Various wreaths and patterns with crescent moons occur on one side, with the celtic horse on the other.

|

|

Addedemorus gold stater

|

|

35 BC

|

The first inscribed celtic coinage from North of the Thames was produced by Addedomarus who may have been leader of the Trinovantes at this time. The Trinovantes territory covered the south of Suffolk and North Essex. Their northern border was with the Iceni, and they would have been dominant in the Haverhill and Clare region of today's St Edmundsbury. Colchester or Camulodunum has always been regarded as a centre of their culture.

|

|

34 BC

|

The Roman Emperors still saw themselves as the rulers of Britain because of the peace treaties made with Julius Caesar. So when there were disturbances in Britain, Octavian decided to gather forces for a punitive expedition. His first planned campaign failed to sail, having to be diverted to quell uprisings in Dalmatia.

|

|

31 BC

|

At around this time , Tasciovanus of the Catuvellauni established his capital at Verulamium, or St. Albans, in Britain, and built it into a powerful trading center.

|

|

Norfolk Boar coin

|

|

30 BC

|

The Catuvellauni became increasingly dominant in Britain. The Roman Emperor Octavian again gathered a British expeditionary force to enforce Roman domination. He was averted by the threat of an uprising in Gaul. In addition he was given the assurance of the Britons good-intent by diplomacy.

In Norfolk and North Suffolk, the Iceni coinage now moved on and a stylised boar appeared on one side of silver coins, with a horse on the other. This coin is called the "Norfolk Boar" type. Some have been found inscribed CANM DURO or versions of this inscription.

|

|

26 BC

|

Octavian had earned the name "Augustus" and the title "Princeps", for his reconstitution of the Roman state. Heartened by this success, Augustus prepared another British campaign. Once again he is thwarted, this time by a revolt of the Selassi. After this third failure he resolved never to attempt to attack Britain again.

|

|

Norfolk God Moustache type

|

|

20 BC

|

In Norfolk and North Suffolk, the Iceni coinage contained other variations. Other Iceni types thought to date from 30 BC to 10 BC are the Face/Horse type. The face has been called the "Norfolk God" type. A variant of this is the "Norfolk God - moustache type".

The other side of the coin retains the Horse motif associated with Celtic coinage, and especially with the Iceni.

In the lands of the Catuvellauni King Addedomaros died, to be succeeded by his son Tasciovanus.

|

|

15 BC

|

Around this time the Catuvellauni were centred on Hertfordshire, with a mint at St Albans (Verulamium). Coinage shows that they seem to have expanded their power and influence over their neighbours, the Trinovantes. Early coins of Tasciovanus of the Catuvellauni were marked VER or VERL, for Verulanium, but a few exist marked CAM. This probably refers to Camulodunum or Colchester in the heart of Trinovante territory. However, his later coins dropped the CAM mark. Later, his coins were marked TASCIO RICON, the celtic equivalent of TASCIO REX or King Tasciovanus.

It seems that Tasciovanus had renewed hostilities against the Trinovantes, violating the treaties made between Julius Caesar and Cassivellaunus, his own grandfather. From 15Bc to 10 BC he took over Colchester, perhaps only withdrawing when Augustus was in Gaul.

There would seem to have been some connection between the two tribes at this time, but it became closer a few years later.

|

|

12 BC

|

The Emperor Augustus launched his armies against Holland and Germany and established a permanent force on the Rhine. Britain exported corn, hides, cattle and iron to the empire to support the Roman military effort and the administrations it set up across the Channel. Britain grew wealthy on this trade and its culture was changed profoundly by this close contact with the Empire.

|

|

5 BC

|

At Silchester, in Hampshire, Tincommius, successor of Commius the Gaul, became a friend of Rome and received a substantial amount of silver bullion as part of the bargain. This was re-minted and used to fund a pro-Roman power base in the south of Britain, to counter the growing anti-Roman tendancies of the Catuvellauni in the Thames Valley and Essex.

|

|

1 BC

|

The birth of Jesus Christ is dated at around this time. By the time of Bede, our modern system of dates "in the year of our lord" or anno domini, was being used. There is no year zero in this system so that 1 BC is followed by 1 AD.

|

|

Antedios bar coin

|

|

1 AD

|

From about 1 AD to 43 AD, the Iceni continued to produce coins, but inscriptions often now occur. Crescent moons and corn ears or wreaths are on one side and a celtic horse on the other. Inscriptions include ANTEDI, thought to refer to Antedios. Another inscription is ECEN, which some people believe refers to the tribal name, ECENI or Iceni, but if so, this is extremely unusual for the time.

|

|

Badwell Ash Trough

Badwell Ash Trough

|

|

|

Archaeological evaluation work in 1998 on a quarry at Shackerland Hall, Badwell Ash, revealed a large timber trough lying on the edge of a buried stream or mere. The quarry is 9 miles (14km) north-east of Bury St Edmunds and the site drops quite steeply into a small valley where the trough has been preserved for some 2,000 years under a thick hill wash layer.

A programme of study has now been started to examine and understand this object. The trough has received an initial inspection by Richard Darrah, an archaeological wood specialist, who also worked on the first West Stow Saxon Village reconstructions.

It is made from high quality oak heartwood and measures 1.30 metre long by 0.57 metre wide and is 0.19 metre deep with a wall thickness of 0.045 metre. The trough has a capacity for between 40 and 50 litres of liquid. It was skilfully shaped so that few toolmarks can be seen and at each end a horizontal lug was left across the full width of the trough with the underside of the lugs left as split so it was still easy to hold.

Examination of the timber indicates that it was made from a quarter of a large tree trunk with some 100 annual growth rings. At present all we can be certain of is that the trough is from the Roman period at the latest and may well be Iron Age in date (c.2000-2500 years ago). It will be particularly exciting if the latter date can be confirmed as Iron Age wooden artefacts are rarely found and the effort put into the construction of this trough indicates that it was a high status object. Perhaps even a great dish associated with Iron Age feasting or some such similar celebration and it does resemble some of the Scottish “butter” troughs in its general shape.

Large wooden artefacts are rarely found in East Anglia so this is an exciting discovery. The trough could be seen at Moyse's Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds until Museum reorganisation in 2006. In February 2007 this object, together with prehistoric, bronze age, iron age and Roman objects, were put on display at the Anglo - Saxon Visitor Centre at the West Stow Country Park.

In about 1AD the Roman writer Strabo described trade with Britain at this time. He listed the exports of Britain to the Roman empire as grain, cattle, gold, silver, iron, hides, slaves and hunting dogs. Britain imported from Rome ivory, chains, necklaces, amber, gems, glass vessels, and similar items of adornment. Britain had to pay high taxes to Rome for this trade, and there seemed to be no need to invade the country to obtain its products.

|

|

6 AD

|

The British king Dubnovellaunus of the the Trinovantes travelled to Rome to see the Emperor Augustus. Dubnovellaunus complained about the oppression of his tribe by Cunobelin of the Catuvellauni. Cunobelin was the son of Tasciovanus of the Catuvellauni who was their king until his death in 10 AD. Cunobelin was thus not the king of his tribe when he was oppressing the Trinovantes.

Clearly, some of the British themselves felt that Rome was their overlord, to be called upon in times of trouble.

|

|

9 AD

|

The Roman governor of Germany, Publius Quinctilius Varus and his three legions, were massacred in the Teutoberger forest by Arminius, warlord of the united Germanic tribes.

In Britain, Cunobelinus took advantage of the turmoil this event caused at Rome. Knowing that Rome could not intervene, he captured the Trinovantian capital of Camulodunum or Colchester. Augustus was powerless to intervene because at that time no legions stood between the German tribes and Rome itself. The situation in Germany was salvaged by the emperor's step-son Tiberius Claudius Nero, who marched from Rome to the Rhine.

Cunobelin was now de facto King of the Trinovantes by right of arms, while his father Tasciovanus was still King of the Catuvellauni.

|

|

10 AD

|

Tasciovanus of the Catuvellauni was succeeded by his son, Cunobelin or Cymbeline who ruled them until about 40 AD. Cunobelin had already conquered and ruled the Trinovantes, and by right of inheritance he now also ruled the Catuvellauni. This gave him a tremendous power base as ruler of these two Belgic tribes. Cunobelin is believed to be the model for King Cymbeline in Shakespeare's play of that name.

|

|

14 AD

|

The Emperor of Rome, Augustus, died in about the year 14 AD. He left the empire in the hands of Tiberius, the victor of Germany. Tiberius was induced to adopt his nephew Germanicus as part of the deal. Germanicus was the grandson of Augustus by his daughter Julia. Tiberius vowed to keep the empire within the limits established by his predecessor, and Britain remained safely outside of political discussion at Rome for the duration of his reign, which lasted until 37 AD.

|

|

Iron Age hoard from Dallinghoo

|

|

15 AD

|

In the Spring of 2008 a metal detectorist found a hoard of gold coins in a pot at Dallinghoo, near Whickham Market in Suffolk. These proved to be very significant because they were coins minted in the Iceni pattern, and hitherto this area had not been particularly associated with the Iceni. The coins all date to before 15AD based upon our current knowledge. One face bears the Iceni horse on two-thirds of the coins, while the reverse shows a single or double crescent moon motif. Some appear to have a floral pattern on the reverse. There were 825 coins in all, showing the fabulous wealth available to someone of this tribe at the time.

|

|

Belgic type pot

|

|

20 AD

|

The iron age enclosure at Burgh shows a long period of occupation. This illustration of a late iron age Belgic type pot was excavated from Burgh by John Dalrymple Treherne some time between 1947 and 1957. It dates from the first century AD, and there were objects from periods earlier than this, and others showing occupation through into the Roman period. This pot was made on a potter's wheel, an innovation which had only come to Britain perhaps 70 years earlier than this date.

In contrast, the smaller, but similarly shaped iron age enclosure at Barnham, was seemingly going out of use at this time.

There had been an enclosed site of about 1 hectare or 2.5 acres, at Barnham since about 180 BC. It was an enclosure formed by two ditches. It has been interpreted as an Iron Age Hill Fort, and although it is Iron Age, it may well have been a religious site rather than a military one. However, it would have been defended had it been attacked. Excavations have revealed a human leg buried in one corner of the enclosure, by a clay line trough. There is no explanation for this. If this was a religious site of the Iceni, it seems to have been abandoned at about this period. Perhaps it was replaced by the great new enclosed building at Gallows Hill at Thetford.

|

|

Cunobelin corn ear

|

|

25 AD

|

The Essex and South Suffolk Trinovantes had been taken over by Cunobelinus of the Catuvellaini from the west. Coins confirm that their accepted ruler was Cunobelinus or Cunobelin, supposedly later the basis for Shakespeare's Cymbeline. He maintained his court at Camulodunum and seems to have moved his main mint and capital from St Albans to Colchester. During his long and powerful rule he issued large numbers of gold, silver and bronze coins of increasingly Romanised designs. About one million of his gold "corn-ear" staters were produced. They have the letters CAMV with an ear of corn on one side and a horse design with CVN on the other.

He continued to rule the combined tribes from Camulodunum for many years, and his capital became the focal point of British politics, learning and trade.

In the lands of the Iceni, in what is now called Norfolk and the northern part of Suffolk, the ruler known only by the letters CAN was succeeded by ANTED, which we interpret from the coinage as Antedios.

Some historians say that the Iceni may have built the Black Ditches at Cavenham to resist the Belgae invasion, although another view is that these were built 400 years later to hold back the Anglo-Saxons.

|

|

Wine amphora from Kedington

|

|

30 AD

|

One of the luxury goods imported from the Roman Empire at this time was wine. This amphora was found at Kedington in 1947 while digging foundations for a house. This large wine jar is dated to the early 1st century AD, and was made in southern Italy. Iron Age chieftains loved to drink wine, and it is possible that this amphora was used as part of the grave goods in the local chief's burial ceremony. Drinking imported wine would have emphasised the family's high status in the locality. This object is on display in the Archaeology Gallery at West Stow.

|

|

33 AD

|

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, "Here Christ was hanged, five thousand two hundred and twenty six years from the beginning of the world."

|

|

37 AD

|

Having had the Emperor Tiberius murdered, Caligula became Emperor, but would only be tolerated until 41 AD.

|

|

Iceni Centre at Gallows Hill

|

|

40 AD

|

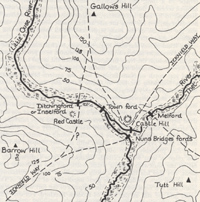

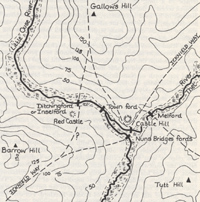

At Gallows Hill, in a location now called Fison Way at Thetford there was a series of hilltop enclosures dating back to the Middle Iron Age. This settlement was replaced, at about the time of the Roman conquest, by a single substantial circular building within a double-ditched enclosure. Outside it was surrounded by smaller peripheral enclosures containing possible graves.

The discovery of this cult centre has led some people to believe that the Iceni "capital" must have been moved here from a site near to Norwich, called Venta. However, there is no indication of a royal presence here, and very little evidence of any major or permanent occupation of this enclosed site.

Whatever its purpose it was of great importance to the Iceni because once built, there would follow a rapid period of expansion. Over the next 20 years the main enclosure will be massively enlarged, with a new outer ditch dug. There will be two further circular buildings put in place and the space between the inner and outer ditches will be packed with rows of upright timbers.

In about 40 AD it seems that Cunobelin became too ill at Colchester to exert his authority over his Catuvellauni and Trinovante followers. Two of his sons now embarked upon a military campaign against Roman influences in the south of England.

Cunobelin, the king of the Catuvellauni, also had a son named Adminius, or Amminus, who was very pro-Roman. Adminius had been given power over Kent by Tiberius in 35 AD, in order to run the trade of that province with Roman Gaul. In the year 40 AD he was expelled from the country by his brothers, Togodumnus and Caratacus, who were resisting the spread of Roman influence. Adminius now travelled through Gaul to Germany to seek help from Emperor Caligula. Caligula was in the grip of madness at this time, and although keen to invade Britain, did not have the ability to proceed. Britain was believed to be right at the end of the earth, surrounded by the great sea Oceanus, which Horace had described as filled with sea monsters. So although Caligula took an army to the coast of France, he could not persuade them to put to sea. All they could do was "gather seashells".

|

|

Cunobelin as a Roman King

|

|

41 AD

|

The insane Emperor Caligula was murdered at the games in Rome, and following some confusion, his uncle Claudius was proclaimed Emperor.

In Britain, Cunobelin, king of the Trinovantes of South Suffolk and Essex, died around this time, following a grave illness. Over his 30 years reign, Cunobelin had built up the most powerful kingdom in celtic Britain, extending his influence south of the Thames and also westwards according to Dio Cassius in his "Roman History". Ruling from Camulodunum, or Colchester, after uniting the Catuvellauni and the Trinovantes, he was powerful enough to be referred to as Britannorum rex, or King of the Britons, by Suetonius in his "Lives of the Caesars". He had ruled a vastly greater area than the Catuvellauni had controlled in 55 BC when Julius Caesar first arrived.

Cunobelin was succeeded by his anti-Roman sons Togodumnus and Caratacus. Verica, a descendant of Commius and king of the Atrebatean kingdom in southern Britain, was ousted from Calleva, or Silchester in Hampshire, by the Catuvellaunian princes and fled to Rome.

This turbulence following the death of the great Cunobelin probably led the emperor Claudius to consider an invasion of Britain. Claudius was only newly made Emperor and badly needed something like a military success to consolidate his position. The appearance of Verica asking for help would have been an ideal opportunity for Claudius to play the man of action.

|

|

Thetford's beginnings

|

|

43 AD

|

The emperor Claudius began the military conquest of Britain, which would remain part of the Roman Empire for the next 370 years. Under treaties made in the time of Julius Caesar Britain was already nominally subject to Rome, but the Celtic Kings had often allowed their ambitions to run counter to these treaties.

At first the Roman army mutinied and refused to risk crossing Oceanus, the unknown seas of Britain, but Narcissus inspired them to proceed.

Four legions and auxiliaries landed at Richborough in Kent, known as Cantium to the Romans, and fought their way to the Thames. Boulogne to Richborough became the main crossing point for the Roman empire in later years.

The legions under General Aulus Plautius were II Augusta, IX Hispana, XIV Gemina and XX Valeria. The future emperor, Flavius Vespasianus [Vespasian], was commander of the second legion during the invasion campaigns. After an unopposed landing, running battles were fought against British chariot forces under the command first of Togodumnus and then Caratacus. These two men were the leaders of the Trinovantes-Catuvellauni alliance, the most powerful of the tribes. The combined British were defeated at a decisive battle on the River Medway, during which Togodumnus received fatal wounds and his younger brother Caratacus was forced to flee with the rest of his family through Gloucestershire to Wales.

The Romans now attacked the homeland of the Catuvellauni, in revenge, and captured their fort at Camulodunum.

Claudius himself led the victorious Roman army into Camulodunum and spent sixteen days in Britain, holding audience with the leaders of several British tribes. Two of the tribes were made clients of Rome because they had played no part in resisting the Roman invasion. First were the Iceni from Norfolk and North Suffolk, and second were the Brigantes from the hilly Pennines in the north.

The Iceni probably did not have a single King at this time, something which confused the Romans. They wanted to deal with one man, and this seems to have been Antedios. Other Iceni chieftains were apparently Aesu and Saenu from coinage evidence. Claudius decided that Antedios was to be the ruler of all the Iceni.

Claudius set up a great temple next to the Celtic settlement of Camulodunum, and dedicated it to himself. Within a few years he would officially found Colchester as capital of the new Roman province of Brittania.

To control Catuvellauni-Trinovante territory it is likely that the Romans also built the forts at Long Melford and Coddenham at this time. Forts were probably not thought necessary inside the Iceni territory of North Suffolk and Norfolk at this time.

|

|

Native Celtic Harness mount

Native Celtic Harness mount

|

|

blank |

The culture the Romans found in Britain had something like 1,500 to 2,000 years of development behind it, and the celtic society was much the same as the Romans found elsewhere in north-western Europe. It was a sophisticated and artistically developed society but it was to be radically changed by the advent of Roman law and the coming of widespread literacy. The population was two or three times greater at this time than it was in the reign of William the Conqueror.

In Norfolk and North Suffolk, the Iceni decided not to fight the Romans, and signed a peace treaty. In return, their king, Antedios was allowed to rule as a 'client' king. Perhaps Antedios felt more secure as a Roman client-king than he had with the Catuvellauni expansion on his southern flank.

This strategy seems to have worked for the next 17 years. At about this time the tribal centre of the Iceni seems to have moved from North West Norfolk to Thetford. A major ceremonial centre was soon to be constructed from thousands of timbers in the form of an artificial "oak grove", at Gallows Hill, not far from Thetford's existing major earthworks and fort.

Roman empire coinage circulated widely and profusely in Britain after this date. Much of it was now brass or bronze. Local celtic coins were also still produced. The Iceni uniquely had their tribal name on their coins as ECE (NI) by this time. This may have been to avoid further conflict over who was the overall King of all the Iceni. Antedios had now removed his name from his coins, perhaps as part of his arrangement with the Romans.

|

|

Late Iron Age cauldron

|

|

45 AD

|

This picture shows the remains of a cauldron from Brandon, which the Suffolk Archaeological Service has dated to c30 to 50 AD. It was one of a group of Bronze containers which were probably used to prepare a drink such as ale for feasts in the very late Iron Age. The cauldron is large (over 50cms across the top) with iron round the rim and iron ring handles. The thin metal has broken at the widest point and at the base. Now on display in the Museum at West Stow.

|

|

47 AD

|

Ostorius Scapula became the Roman Governor of Britain until 52 AD, and in 47 AD he enforced the Roman law of Lex Julia de armis, which prohibited celtic warriors from carrying their weapons. This law was enforced upon the Iceni as well, despite their nominal independence. According to the Roman historian Tacitus, some of the Iceni rebelled and retreated into fortified earthworks, possibly Stonea Camp in the fens or Holkham camp in the North Norfolk salt marsh. At any event they were decisively defeated, and apparently, that was the end of Antedios, Aesu and Saenu.

Perhaps as a reward for not joining in the rebellion, the Roman Governor now made Prasutagus the client king of the Iceni.

|

|

49 AD

|

By order of Rome, the Colony of Camulodunum was officially established under the Emperor Claudius at Colchester. This was official recognition that the old established Celtic centre of Camulodunum was now part of the Roman administrative system.

|

|

Gallows Hill Religious Centre enlarged

|

|

50 AD

|

At some point after the Roman invasion, the great Iceni religious centre at Gallows Hill, outside modern Thetford, was enlarged. An outer ditch was added to enclose a total area of 11 acres, and the 30 yard space between inner and outer ditches was filled with row upon row of wooden fencing or pallisades. The existing single building was supplemented by two more buildings on either side. The interior of the enclosure was thus doubled in size, indicating the power and prestige which the Iceni King could still command, even under Roman rule.

A straight corridor running between stout wooden fences of upright posts led, via a massive timber gateway, into an inner enclosure some 80m (265ft) wide and 140m (460ft) long. Anyone entering this would have been faced by a largely empty arena, to the rear of which stood a major building, with two more on either side. It has been called a two-storied Romano-Celtic temple within an extensive 'artificial oak grove'.

The enclosure which was now enlarged was probably only about ten years old.

The major investment of resources over a relatively short time indicates the importance of this grand and unusual site. Evidence for agricultural production and domestic occupation is scarce, compared to metal-working debris, including coin moulds. Tony Gregory, the author of "Excavations in Thetford 1980–82, Fison Way", argues that this exceptional site was a uniquely important religious, tribal and ceremonial centre for the Iceni.

Under King Prasutagus, the Iceni coinage became romanised. The horse became more realistic and less stylised, the face became a bust rather than a mask. The inscription has been said to read SVB RI PRASTO ESICO FECIT or "under King Prasto, Esico made me". This inscription has recently been called into question.

|

|

54 AD

|

The Emperor Claudius, the invader of Britannia, was poisoned by a dish of mushrooms given to him by his wife, who was also his niece, Agrippina. Agrippina's son Nero now became emperor.

|

|

59 AD

|

Under the terms of Client Kingship all of a Client King's lands and possessions had to be left to the Emperor when the client king died. Normally the Emperor would then formally hand them all back to the appropriate heir, and make a new client-king arrangement with him, personally. Unfortunately Prasutagus had no sons, but it was quite acceptable within the Celtic world for the inheritance to pass to a King's daughters. Rome, however, had no such arrangements, and women were treated as subject to their husbands, fathers, or a protecting male relative, having no official position in their own right. Prasutagus was in a dilemma, as he believed that Rome would never hand back rulership to his daughters after his death. So he attempted to set up a compromise.

In the Winter of 59 AD, Prasutagus died, dividing his kingdom and fortune, leaving half to his two daughters and half to the Roman Emperor Nero. This was not enough to appease Nero, and the Romans began to revoke the grants and bequests to Prasutagus. Seneca and others began calling-in loans to Icenian noblemen. The legionaries sent into the kingdom to keep order actually cause an escalation of the problem. A civil disturbance in the Icenian capital was brutally crushed, the king's daughters raped and his wife Boudicca publicly flogged.

We can imagine that a council of war was called, probably in the enclosure at Gallows Hill, Thetford, to decide what to do.

The Iceni had been goaded into revolt, and were soon joined by the Trinovante-Catuvellauni alliance. Weapons were assembled and part of preparations for war included testing the tribe's battle trumpet or Carnyx.

|

|

Iron Age carnyx

|

|

blank |

In 2025

a near-complete battle trumpet and a bronze boar's head which once adorned a military standard are among a hoard of "remarkable" Iron Age objects discovered in Norfolk. The bronze trumpet - known as a carnyx - is one of only three ever located in Britain and one of the most complete discovered in Europe. The animal-headed instruments were used by Celtic tribes across Europe to inspire their warriors in battle and fascinated the Romans, who frequently depicted them as war trophies.

The internationally-significant hoard also included a sheet-bronze boar’s head, originally from a military standard.

Five shield bosses and a mysterious iron object, which has puzzled archaeologists, were also discovered in the region of Thetford, during work on a new housing development.

Dr Tim Pestell, senior curator of archaeology for Norfolk Museums Service, said: “This find is a powerful reminder of Norfolk’s Iron Age past which, through the story of Boudica and the Iceni people, still retains its capacity to fascinate the British public."

“The Norfolk Carnyx Hoard will provide archaeologists with an unparalleled opportunity to investigate a number of rare objects, and ultimately to tell the story of how these came to be buried in the county 2,000 years ago.”

|

|

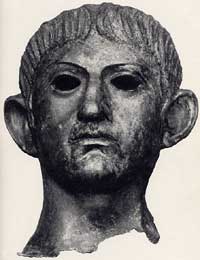

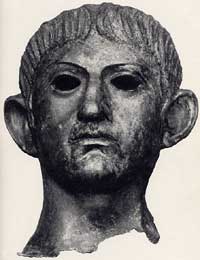

Emperor Claudius

|

|

60 AD

|

Boudicca of the Iceni now allied with the Essex and East Suffolk Trinovantes to attack the Romans. Following a two day siege they took Colchester, smashed the temple of Claudius and destroyed the garrison. The IXth Legion marched south from near Peterborough to quell the revolt but was ambushed in the wooded Stour valley near Haverhill. The Roman Commander of the IXth Legion from Longthorpe was Petilius Cerialis who barely escaped with his life and a few cavalry men. The location of this battle is not known, but there is a local tradition that it took place in Blood Field at Great Wratting. The Romans lost 1,000 men, and no doubt, flushed with success, the uprising turned south and west.

Various artefacts from this period have been found scattered around Suffolk. Here we see a bronze head of Emperor Claudius. It was probably broken off from a large bronze figure of the emperor, and is thought to have been looted from Colchester, and finally dumped in the River Alde at Rendham.

|

|

Hawkedon gladiator helmet

|

|

blank |

This gladiator's helmet was found at Hawkedon in Suffolk. It dates to the 1st century AD and was found about 20 miles from Colchester. Colchester had a large Circus which has recently been excavated, and gladiatorial contests took place there. The helmet may have been loot from the attack on Colchester, or it is possible that a retired gladiator from the Colchester colony had moved out to the Suffolk countryside.

Having sacked Colchester the rebels then reduced London and Verulamium (St Albans) to a layer of ashes. Tacitus reported that when Boudica sacked London, "all those left behind were butchered. The British took no prisoners nor did they consider the money they could get from selling slaves. It was the sword, gibbet, fire and cross". Dio Cassius described atrocities committed by the Iceni who worshipped Andraste, their invincible war goddess.

By now Cerialis had sent word to Paulinus who was campaigning in Wales. Most of the Roman army was with him in Anglesey, destroying the druids and last major celtic strong hold. Paulinus hurried back along Watling Street, the modern A5. Eventually Boudica faced the Roman Commander, Suetonius Paulinus in battle in the vicinity of Bath. Tacitus recorded in his Annals that "it was a glorious victory equal to those of the good old days: some estimate as many as 80,000 British dead. Boudicca ended her life with poison". Agricola began his career in Roman public life as a military tribune, serving in Britain under Governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus from AD 58 to 62. He was probably attached to the Legio II Augusta, but was chosen to serve on Suetonius's staff and thus almost certainly participated in the suppression of Boudica's uprising in 60 or 61.

|

|

Statuette of Nero

|

|

blank |

The rebellion of Boudicca against the Romans brought reprisals and the firm establishment of Roman rule. Roman reprisals were at first extreme. It is significant that the Iron Age settlement at West Stow ended about this time; but it is not known just what happened. The Iceni religious wooden timbered henge at Thetford was also demolished around this time. Iceni coinage production also ceased or was suppressed at this time. The Iceni were eventually allowed to survive ruled from Venta Icenorum (Caistor St Edmund), near Norwich. A new seven acre Roman fort was established at Pakenham on the Peddars Way to control the ford across the River Blackbourne and maintain control over the locals. Peddars Way was built from Chelmsford through Long Melford, Pakenham and Ixworth and Knettishall towards the Wash at Holme-next-the-Sea. The old A45 (now A14) from Kentford to Bury was probably a link road from the prehistoric Icknield Way at Icklingham to the Romanised Peddars Way linking via Fornham and Great Barton.

Another road probably already ran from Cambridge to Haverhill and Clare and on to Long Melford on the northern side of the River Stour. It would become less important as a frontier road once the Iceni came under Roman military occupation.

It is important to realise that the description 'Roman' really equates with Romanised Britons. So 'Roman' settlements flourished in the river valleys and light soils but continued the iron age penetration of the heavy clay soils as well. Roman kilns have been found at Wattisfield, West Stow and Icklingham etc, where the local clay was suitable.

The Romano-British landscape was ordered much like the medieval one with open market centres in an agricultural landscape. In our area such centres were Icklingham, Pakenham, Wixoe and Long Melford. Coddenham was a major centre to the east. Sicklesmere was a smaller settlement.

|

|

Fison Way at Thetford

|

|

61 AD

|

In 1982 the Fison Way Industrial Estate was being developed at Thetford. Aerial photography of Gallows Hill, behind the new Travenol factory, revealed three round buildings enclosed by a rectangular enclosure. This has been interpreted as an Iceni tribal or religious centre. It dates to a period of decades leading up to 60 AD to 70 AD, and seems to have been destroyed before it was completed. It is tempting to view its construction as a form of hill fort, although it does not have any evidence of a military purpose, despite being enclosed by multiple trenches containing posts. However its destruction may well have been part of the Roman reprisals afterwards.

The settlement within the enclosure at Burgh, near Woodbridge, was also flattened at this time.

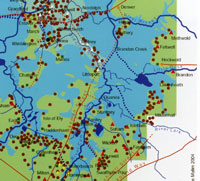

During the uprising led by Boudica and in the following Roman suppression, many of the Iceni deposited hoards of coins in the ground for safe-keeping. Over ten hoards have been discovered in Norfolk from this period, and half of them contain mixed Iceni silver units and Roman denarii. The most recent hoard was found at Forncett in Norfolk in 1996 with 381 silver coins of which 336 were Iceni, and 45 were Roman.

The Roman coins from the Forncett hoard date from 128 BC through to AD 36 and no doubt the Celtic Iceni coins also span a similar period.

These hoards of the Boudican period are clustered in south east Norfolk and the north of Suffolk. There are clusters around Norwich and around Thetford, spreading eastwards along the River Waveney.

Around this time fifty gold coins supposedly bearing the head of Prasutagus (Boadicea's husband) were buried on the Chalkstone Hills at Haverhill and were to be discovered by labourers in 1787. It would be interesting to examine these coins in the light of modern knowledge, as this is not in an area usually associated with the Iceni.

|

|

Coddenham Roman Forts

|

|

65 AD

|

This is an aerial photograph showing cropmarks which include parts of two first century Roman forts. The three ditches of one fort can be seen clearly on the left, showing as parallel dark green lines turning a corner near the top of the picture. The pale line running across the photograph is the Roman road from Colchester to Caister (followed by the modern A140 for most of the route). These forts are dated to between c 43 AD and 65 AD.

|

|

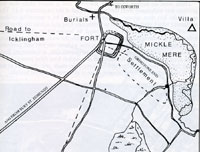

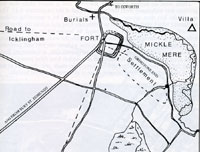

Pakenham Roman Fort

|

|

75 AD

|

Before the Ixworth bypass was constructed, Judith Plouviez, of the Suffolk County Council Archaeological Unit, excavated along the proposed road line, as it was known that it crossed a Roman fort. Existence of this fort had been known since it was seen from the air in 1945 just outside Ixworth but located within the parish of Pakenham. The fort was shown to have been used for a short time after the revolt of Boudicca (Boadicea) in A.D. 60, after which it became a small town with timber buildings and gravel roads. During the excavations over 1000 coins were found, also 100 brooches, iron tools and thousands of pieces of pottery, showing that this was a flourishing local market town, complete with industry and which lasted throughout the 350 years of Roman rule. The oldest coin bears the head of Trajan (A.D.98-117) with "Victory" on the reverse, facing a pile of arms. The smallest clearly shows the helmeted head of Constantine I (A.D. 307-337).

Roads led into this settlement from several directions. Going west, a road ran to Icklingham, with a branch off to the villa located at Redcastle Farm. From the south a road came from Long Melford. Going north a road connected to Stanton, where it divided into two, one route going to the Wash following the Peddars Way, and one route going to the major settlement at Venta Icenorum.

|

|

78 AD

|

Gnaeus Julius Agricola was appointed governor of Britain by Vespasian. Agricola's first campaign resulted in the defeat of the Ordovices in North Wales and the conquest of Anglesey.

|

|

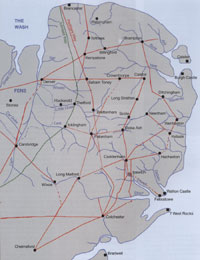

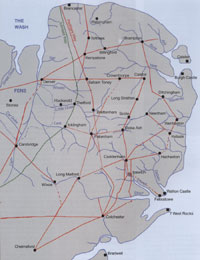

Roman coast and roads

John Fairclough

|

|

90 AD

|

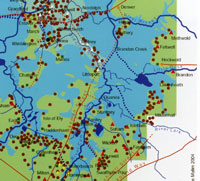

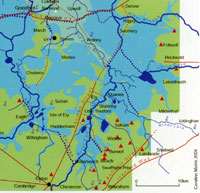

What did Roman Britain look like? Despite our great knowledge of the Roman civilisation from its physical remains, we do not know how the landscape looked at the time. The coastline was not the same as at present, and inland waterways seem to have been larger and deeper than we are used to today. Were the Fens an inland sea? Were all Roman roads laid out in a dead straight line?

John Fairclough has addressed some of these issues in his 2010 book, "Boudica to Raedwald - East Anglia's relations with Rome." His sketch map of the known major roads of the time is attached here. He shows the sea coast extending south into the Fens down to Denver, and a great estuary guarded by forts at Caistor band Burgh Castle. Similarly the estuary of the Orwell and the Stour, behind Felixstowe, are larger than today, while a promontory out to West Rocks is conjectured. Coastal areas which we know today are eroding rapidly could have been two or more miles further out to sea in the Roman period.

Settlements known to to have been active at the time are also shown, like Thetford, Icklingham, Long Melford and Pakenham, while there is no sign of Bury St Edmunds or Norwich to be seen.

|

|

95 AD

|

The colony of Lindum was established under Domitian at Lincoln. A couple of years later Glevum was established under Nerva at Gloucester.

|

|

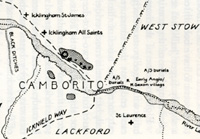

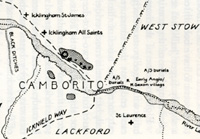

Camborito at Icklingham

|

|

100 AD

|

By the end of the 1st century there were six small "Roman" towns in Suffolk. Their inhabitants would have been largely the native inhabitants, but with officials answerable to the Roman Empire, and a smattering of peoples from across the countries of the Empire. Administration of the area was probably from either Venta Icenorum, (Caister by Norwich), or Colchester.

Most, if not all, of these towns would have been existing settlements of the existing celtic tribes.

The six towns, from west to east, were:

- Icklingham

- Long Melford

- Pakenham

- Coddenham

- Scole

- Hacheston

|

|

Cropmarks of Lidgate Villa

|

|

blank |

By the second century brick and stone was used in building. A villa has been identified at Rougham together with pottery and glass finds from burial sites in nearby tumuli. Villas have also been found at Ixworth, Pakenham, Mildenhall, Stanton and Lidgate.

|

|

Cremation urns from Rougham

|

|

blank |

The villa settlement at Rougham probably survived for at least a century, as a series of cremations have been found in four mounds or barrows. These Four Hills were a line of Roman burial mounds that stood at the edge of Rougham parish. The Four Hills were almost certainly the burial place of the family who lived in a nearby villa, discovered at about the same time.

The Roman Britains were still pagan at this time and used cremation, rather than burial, and the burnt remains were interred in pots, together with grave goods. Eastlow Hill is the remaining mound at Rougham today, but three other mounds existed in a line to the south-west in 1843-44, when they were excavated. One mound contained a lead coffin, in a brick lined burial chamber.

They were a group of conical tumuli from the 2nd or 3rd century AD, standing beside Eastlowhill Road, an extension of Peddar's Way. The excavation showed that the cemetery was in use at least until the late 3rd century.

Remains of a substantial Roman building have recently been unearthed on the outskirts of Haverhill, dating probably from the second century AD. This, together with other finds and the close proximity of a Roman road running along the high ground to the north, point to a long occupation during the days of the Roman Empire. A Roman burial ground was found in Castle Walk, and a Roman settlement was excavated on the Coupals Way estate. At Coupals Way occupation extended from the iron age to the 4th century.

|

|

Old engraving of Bartlow Hills

|

|

blank |

The Bartlow Hills are probably the best preserved burial mounds from this Roman period of the late 1st century and early second. As they are "younger" they tend to survive as larger mounds than the pre-historic examples. Bartlow Hills was originally the largest group of Roman barrows in northern Europe and still includes the highest burial mound in Britain. The seven original mounds covered extraordinarily rich burials containing a wonderful collection of artistic objects.

There are three remaining hills from the original seven. The others have been lost by Victorian excavations, and the coming of the railway, which passed through the whole group. The main mound is called Mound IV, and is the largest, at 45 feet high and 144 feet in diameter. Mound II is still visible as a low rise, I is just discernible and the rest are totally destroyed. Their steep conical shape, originally surrounded by a ditch, is typical of Roman burial mounds.

Large wooden chests with iron fittings were found in five mounds and there was a brick cist in another.

Cremated burials, with food and drink in exotic vessels of decorated bronze, glass, and potter and other sacrificial offerings had been deposited in the chests, which were buried with lamps still burning in them. Items found included an iron folding chair and remains of flowers, box leaves, a sponge, incense, and liquids including blood, milk and wine mixed with honey.

Burial mounds of this type were built in the late first and early second centuries AD in Eastern England and Belgium. Most artifacts in them show the high status of the owner; they were usually imported from the Rhineland and Northern Gaul.

In the next three centuries, Roman villas and other settlements flourished at Castle Camps, Haverhill, Ridgewell and Wixoe, and a Roman cemetery was discovered at Withersfield in the eighteenth century. The River Stour was probably navigable as far as Wixoe, and Wixoe may well have been the most important of these settlements. The main road through Cambridge, the Via Devana which originated in Chester, has been traced as far as Withersfield, and may have gone on through Haverhill to Long Melford and Colchester.

|

|

122 AD

|

Hadrians Wall was built from Wallsend to the Solway Firth. It took only six years.

|

|

Venta Icenorum

Venta Icenorum

|

|

130 AD

|

The Norfolk town of Venta Icenorum was probably established after the Boudiccan Revolt, and may have been a military camp at first. The Romans needed an administrative centre for the Iceni, and for some reason this site at Caistor St Edmund, near Norwich was chosen. It may have been that it was already an important Iceni centre, but there is no evidence of that. It seems more likely that it was placed deliberately to weaken the Iceni centre at Thetford. It could be that this site also favoured elements of the Iceni who were more ready to accept Roman rule, and reject the old celtic ways.

Caistor St Edmund (Venta Icenorum) is one of only three Roman regional capitals in Britain that were not succeeded by medieval and modern towns, the others are Wroxeter and Silchester.

The Roman administered area centred on Venta Icenorum probably covered all the old Iceni tribal area of Norfolk and northern Suffolk as far south as the Lark and Gipping Valleys. This area would have included Icklingham, Pakenham, Wattisfield and any villas around Bury St Edmunds such as at Thurston, Sicklesmere, and Stanton.

At first the town buildings would have been wooden, and were upgraded to stone as the circumstances of individuals improved. It is clearly on a formal grid pattern, with owners being allocated plots of land within each insula, which was a block within the street pattern.

By the middle of the 2nd century work began on the construction of the town's Forum and Basilica. These would house the local administration, who up to now had been lodged in ordinary town buildings.

By about 80AD Venta Icenorum may have first been laid out on a fairly grand scale. After about 200 AD it was not growing as first expected. The picture here shows its final form, when it was enclosed, on a smaller scale, for protection from the barbarian incursions in the 4th century.

Venta was found by aerial photography in 1928, when the drought caused cropmarks to appear, and the site was photographed by the RAF. It was first excavated in 1929 and 1935.

|

|

Roman temple at Caistor St Edmund

|

|

blank |

More modern excavations continued into the 21st century, culminating with the community archaeology group known as "Caistor Roman Project." In September, 2020 they revealed that 'One of largest' Roman Britain temples ever found was here in Norfolk. The 2nd Century temple site at Caistor St Edmund, near Norwich, has been known about since 1957, but its true scale has only just emerged.

It was built by the Iceni tribe, best known for their leader Boudicca who rebelled against the Romans in AD61. The 2nd Century building, which was built on the site of an earlier Romano-Celtic temple, was surrounded by a precinct with two gates.

Archaeologist Prof Will Bowden said its size, 20m by 20m (65ft by 65ft), showed "how important this cult was to the Iceni". He said it was "one of the largest of its type in Roman Britain" which "indicates not only the importance with which the site was regarded but also that the Iceni had the resources to construct major public buildings should they choose to".

Caistor was the site of Venta Icenorum, the smallest Roman regional capital in Britain.

Its forum - the main public building - was less than a quarter of the size of Verulamium, now known as St Albans, whereas this temple was one of the largest.

|

|

The Fens in Roman times

The Fens in Roman times

|

|

140 AD

|

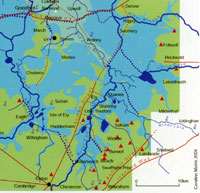

During the time of the Emperors Hadrian and Antony, from 120 to 140, much of the infrastructure of the Roman Fens was put in place. The map shows an intensive cluster of settlements along the fenland edge, indicating a prosperity and activity which has not been fully recognised in the past. The Fenland edge was a hive of activity in Roman times, with trading boats coming and going, industrial workshops and settlements supported by the rich natural resources of fish and game available from the waters. Summer grazing was widespread on the water meadows, and thatching reeds were widely available.

Hockwold in particular became an important port in the area.

|

|

Roman Barn, Beck Row

Roman Barn, Beck Row

|

|

| |

150 AD

|

The picture shows a Roman timber barn, which was excavated in 1999 by the Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service at Beck Row. It dates from the 2nd century and was used for processing crops. The dark soil areas are the remains of cut features such as ditches on the right hand side. In the middle distance two rows of brown spots indicate where large timber posts stood, with a slighter row to the left. Patches of chalk can be seen inside the building, and included a burnt flue, probably the remains of a malting kiln. Overall the building was 30m long and 10m wide.

|

|

Field place names

Field place names

|

|

| |

175 AD

|

From about 100 AD until the 4th century, there was a flourishing pottery industry around the area of Wattisfield. Probably the main reason for this was the good local clay which supported a pottery industry here right through to the medieval period. However, fuel and water were also necessary. Norman Scarfe has suggested that the names Wattisfield and the nearby Ashfield indicate the presence of coppice woodland necessary for the large quantities of wood needed to fire these kilns. Ash wood brought from from Ashfield would have been useful in the long slow burn needed once a kiln has been brought up to temperature by quicker burning woods.

Norman Scarfe suggests that these place names date back to this Roman period.

|

|

200 AD

|

Britain largely escaped the crises befalling the empire on the continent in the 3rd Century, enabling an increase in prosperity. However, Saxon visitors first appeared along the East Coast early in the 3rd Century and by the end of the Century, were raiding as far as the Bay of Biscay.

|

|

205

|

Between 205 and 208 AD, Severus re-built Hadrians Wall to keep out the Picts.

|

|

Roman roads

Roman roads

|

|

| |

210 AD

|

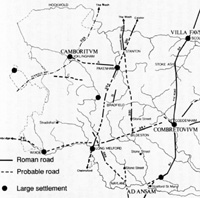

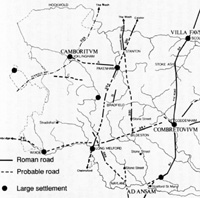

All free born men in the Provinces, including Britain, were declared full Roman citizens, rather than subject peoples. Around this time the 'Antonine Itinerary' was drawn up which named locations in Britain and their distances apart. This is the main evidence for suggesting that Icklingham was known as Camboritum and Coddenham was called Combretovium. The location of the Villa Faustini remains uncertain but Scole is the most favoured possibility today.

The numbers on the roads on the attached maps are taken from 'Roman Roads in Britain' by Ivan D Margary, published in 1973. The first map shown here was published in 1988 in 'The Archaeology of Roman Suffolk' by Moore, Plouviez, West, 1988. Note that at that time Sitomagus was thought tentatively to be Knoddishall. More on Sitomagus below.

From the west, road 333 is the old Icknield Way, following the prehistoric route from Wiltshire to the Wash, along the chalk ridge. Parts of it were straightened by the Romans. It passes between Camboritum at Icklingham and the site of anglo saxon Stowa which was settled after 440.

Road 24 runs from Cambridge to Colchester via Wixoe. This route was taken by the 9th Legion when they marched from Peterborough to avenge the sack of Colchester in AD 60. They were ambushed along the road outside Haverhill.

Road 33a runs from Chelmsford, through Long Melford, to Pakenham, then it becomes 33b, and runs through Stanton and up to Holme and the Wash. At Stanton there is a road junction, and from here 33a could equally join road 330 and continue north to Venta Icenorum (Caister by Norwich).

Road 330 has not been fully identified along its route south from Stanton. It may have passed by Pakenham, but then aims south east to Bildeston to either join or cross road 34a. If it crossed 34a, then it was probably a direct line to Colchester.

Road 34a joined up the Cambridge-Wixoe-Melford road (24) with Combretovium. Combretovium is usually interpreted as Coddenham, but although it is in Coddenham parish, the nearest village is actually Baylham.

The fort and settlement at Combretovium was on an important river crossing of the Gipping. Road 3 runs from Colchester to a settlement near Stratford St Mary, then to Combretovium, and on to Scole, which is now believed to be the Villa Faustini mentioned in the Antonine Itinerary. From Scole the road proceeds up to Venta Icenorum at Caister by Norwich. In Medieval times this was known as the Pye Road.

In the past there was a long running feeling locally that Bury St Edmunds was the site of the Villa Faustini, and, as such, it featured in the pageant of 1907. However by that date, local historians had largely accepted that there were no Roman remains at Bury. So it was also supposed that perhaps the Villa Faustini was at Sicklesmere, where there were some Roman artefacts. Twentieth century archaeological discoveries at Scole have provided new evidence that now shifts the likely site to that vicinity. However, David Ratledge does not find this very likely because the mileages are wrong, so Villa Faustini must remain a "lost" villa for the present.

|

|

Roman roads by David Ratledge

|

|

blank |

By the 21st century the use of LIDAR was becoming available to academics, and later freely available to the public. Using Lidar images dedicated researchers like David Ratledge have published many suggestions for new Roman roads and routes. New Suffolk roads can be seen at this website:-

David Ratledge's website for Suffolk Roman Roads.