Market Hill c. 1700

Quick links on this page

First Suffolk turnpikes 1711

River Lark canalised 1716

Trial of Arundel Coke 1722

Kirby's Suffolk Traveller 1735

Bury to London same day 1737

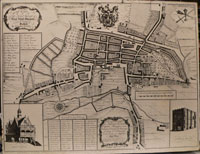

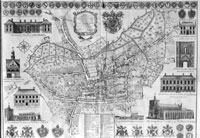

Downing's map of Bury 1741

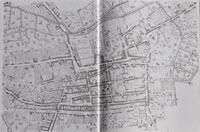

Warren's map of Bury 1748

The modern calendar 1752

New butchers' shambles 1761

Turnpike to Newmarket 1770

Warren's updated map 1776

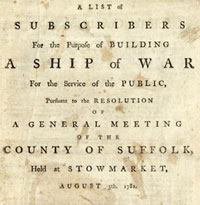

Godfrey's East Prospect of Abbey 1779

Fornham Park enclosed 1782

The French Revolution 1789

Napoleonic Wars begin 1793

End of Bury wool trade 1800

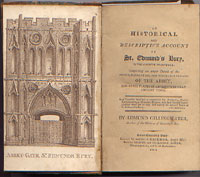

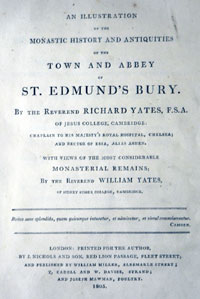

Richard Yates's Antiquities 1805

Buck & Greene brewers 1806

Suffolk livestock 1810

Foot of Page 1812

|

The Eighteenth Century

and Napoleonic Wars

From 1700 to 1812

Pre-

1700

|

Please click here if you wish to view events leading up to 1700.

|

|

1700 |

By the end of the 18th century the Guildhall Feoffees had built a Dispensary in Angel Lane to provide out-patient care to the poor of Bury.

In Haverhill as the seventeenth century gave place to the eighteenth, weaving began to expand in the town, no doubt as a result of the influence of Flemish Huguenot refugees who had settled in the eastern counties late in the seventeenth century, following the French King Louis XIV's revocation of the Edict of Nantes. In 1685 Louis decided to outlaw Protestantism in France, which had been tolerated in selected cities since the Edict of Nantes in 1598. After he revoked the Edict, Protestants were persecuted in France, and hundreds of thousands went abroad. About 50,000 came to England.

The year began with one of the coldest winters on record. Freezing NNE winds continued to blow through April and May.

|

|

1701

|

The Reverend John Beart became pastor of the Independent Congregation in Bury St Edmunds. He continued to take the Independent cause to Chevington and the villages south of Bury. Sir Thomas Felton replaced Sir Robert Davers as Bury's second MP, but within a year Davers was back to replace John Hervey when Hervey became a peer.

By 1701 Parliament had become desperately worried about the future of the monarchy. William and Mary had produced no heirs. Although Mary's sister, Anne, could succeed to the throne, she had also failed to produce an heir who had survived beyond childhood. In order to settle this issue in advance, Parliament passed the Act of Settlement of 1701. This Act settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns and thrones on the Electress Sophia of Hanover (a granddaughter of James I) and her non-Roman Catholic heirs. The other surviving Stuarts were all Roman Catholics, and they were excluded by this Act.

|

|

1702

|

In 1689, following the "Glorious Revolution", the throne was offered to William and Mary, who became William III and Mary II. Queen Mary had died of smallpox in 1694, leaving William to reign alone until 1702.

In March, 1702, King William III died, and Queen Anne came to the throne on 8th March. Queen Anne, like her predecessor Queen Mary II, was a daughter of James II, who had fled the country in 1688. The new Queen was in ill health, having suffered over a dozen miscarriages and stillbirths, and being afflicted by a gout like symptoms. Anne was crowned on St George's Day, 23 April 1702, but had to be carried there in a sedan chair.

One of Bury's two MP's, John Hervey, was created a Baron on the succession of Queen Anne. Once elevated to the House of Lords, he ceased to be Bury's MP. By now, Suffolk was dominated by the Tory party who controlled both County parliamentary seats. Notable local Tories were Sir Robert Davers of Rushbrooke and Sir Thomas Hanmer of Mildenhall. John Hervey MP was replaced by Sir Robert Davers.

John Hervey had been a regular visitor to Newmarket from 1690, and into the 1700s to attend the races and for all forms of gambling. Like other well to do men, he liked to enter the court circuit whenever royalty was in town.

The house now called Angel Corner was built on the Angel Hill in Bury.

There had been a ditch in front of the abbey gate for drainage purposes for many years. Some writers had even called it Canute's Ditch. There is evidence that the ditch was still there in 1702, and that the lower part of the Angel Hill was lower than it is now.

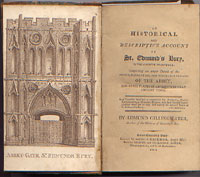

In Edmund Gillingwater's "Historical and Descriptive Account of St Edmundsbury" of 1804, he claimed that "The ditch was open at the beginning of the last century". By 1804 he wrote that "The whole of the Angel-hill appears to have been raised and levelled by filling up the ditch near the Abbey-gate, where the ground was so low, that people ascended the houses on the opposite side, by several steps. The ground near the gate is now much raised, it is said three feet."

|

|

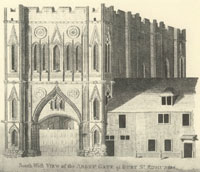

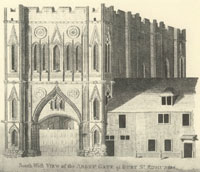

Abbey Gate early 18th century

Abbey Gate early 18th century

|

|

1703

|

One of the two Bury MP's, Sir Robert Davers, bought the manor of Rushbrooke.The estate included Little Welnetham. He owned sugar plantations in Barbados, planted by the first Robert Davers from 1635 onwards. Despite his wealth, he seems to have been unable to read and write, having been brought up to run the slaves on the plantation. He continued as an MP and died in 1722.

The other Bury MP, John Hervey, had just been created a Baron on the succession of Queen Anne. In March 1703 he received his letters patent and the motto "je n'oublieray jamais". Once elevated to the House of Lords, he ceased to be Bury's MP, and was replaced by Sir Robert Davers.

Baron Hervey would not be made 1st Earl of Bristol for another eleven years, and at this time the family lived in the old Ickworth Manor House, which was located just south of the Ickworth Church. To complement the house he built the Summer House and Walled Garden which still stands overlooking the Canal, which he also had constructed, by digging out the valley of the tiny River Linnet, and damming it up.

The old Manor House dated back to the 15th or 16th centuries, and at this time he probably intended to have it rebuilt on or near this site.

On the night of 26th and 27th of November, 1703, came the worst storm to hit Britain in recorded history. It was worse than the storms of October 1987, and more destructive than the East Coast floods of 1953.

The turrets over the stairs at the Abbey Gate seem to have fallen, and been removed, in the early 18th century. Some of the damage may have arisen during this storm, although this is a speculation at present.

There were estimated to be 8,000 deaths across the country as church steeples fell, and cottage roofs blew away. Windmills caught fire as the sails spun causing such friction as to generate great heat. Winds of over 90 mph were experienced in East Anglia.

Kings College Chapel was badly damaged, as were many other churches. Defoe claimed that lead had been torn from the roofs of 100 churches.

Things were worse at sea. Hundreds drowned off the coast of Norfolk and Suffolk. Some 8,000 sailors in the British fleet were drowned, as hundreds of vessels sank, including four Men-of War.

In 1703 the Drury family lived at Wrigglesworth Hall, near Thetford. Here a chimney fell in and killed Lady Drury, also known as Dame Eleanor Drury.

|

|

1704

|

In medieval times the practice of giving one tenth of the production of agricultural produce to the church had already been well established. Monasteries erected tithe barns to hold the grain, and much of this had supported the clergy as well as some being redistributed to the poor. By 1547 King Henry VIII had confiscated the payment of tithes to the catholic church, and often had sold the rights to new lay landowners or "lay impropriators". What was left was payable to the Church of England. Various means arose over the years to avoid church tithes, and the result of all this was that by 1704 most country parsons were left with only a very small income, while the right to tithes were seen to profit already wealthy landowners.

Gilbert Burnett, the Bishop of Salisbury, persuaded Queen Anne that help was needed, and this resulted in 'Queen Anne's Bounty for the Augmentation of the Maintenance of the Poor Clergy.' All the royal revenues from First Fruits and Tenths would be paid to the clergy.

This act would reignite the enforcement, and the resistance to, tithe payments right up to the late 20th century.

|

|

Queen Anne 1702-1714

Queen Anne 1702-1714

|

|

1705

|

About this time the first Congregationalist Chapel was dedicated in Whiting Street, Bury St Edmunds. Before this time, members mostly met in private houses, and it is likely that the chapel was an adapted house. A proper purpose built church had to wait another ten years.

There was a General Election and Suffolk again produced a majority of Tory MP's. In 1705, eleven of the Suffolk MP's out of sixteen were Tory. This seems to be a turn around from the days of 1640 to 1660 when Suffolk was radically puritan and anti-establishment. In 1679 Suffolk returned mostly Whig MP's but by 1705 former parliamentarians were now high Tories such as Thomas Bright of Pakenham. Other former parliamentarians were now Tory MP's in Suffolk like Sir Edmund Bacon MP, Sir Charles Blois MP and John Bence MP.

In 1705, Queen Anne made her first visit to stay at the palace in Newmarket since becoming Queen. Her stay was for 11 days over the Easter period, from April 10th to the 20th. Her visits to church, and to view the races, had to be carried out by way of her sedan chair, because her mobility was restricted by illness.

She also ordered a small extension to be built on to the Newmarket Palace for her own apartments, with a bedroom and dressing room decorated to her own taste.

She became very popular with the people, as well as with the clergy. During her stay at Newmarket she received a petition from the Newmarket clergy thanking her for her benificence in providing Queen Anne's Bounty, a payment to poor clergy begun in 1704. She also gave a sum of £1,000 to provide for paving the streets of Newmarket during the same visit.

|

|

1706

|

In 1706 the manor of Great Barton was sold to Thomas Folkes, a lawyer from Bury St Edmunds. The previous owners were the Audley family, who had held great Barton since 1553. Folkes's daughter, Elizabeth, would inherit the estate. In 1724 she would marry Sir Thomas Hanmer, and he would eventually leave it to his nephew, the Reverend Sir William Bunbury.

In 1706 Queen Anne passed another 11 days at Newmarket, from October 2nd to the 12th. During this visit she was attended by the court, as usual, together with George, the son of Sophia of Hanover. George was appointed the Duke of Cambridge at this time, to emphasise the fact that he was now second in line to the throne of England and Ireland, after his mother, Sophia.

Queen Anne would only make one further visit to Newmarket in 1707.

|

|

1707

|

The Act of Union joined England and Scotland, ensuring that Scotland could not install a rival Stuart as King upon Queen Anne's demise. This meant that after Queen Anne's death, Scotland would also be subject to the 1701 Act of Settlement.

In Bury there were a series of about five separate fires in the centre of town between 1702 and 1707, around the Churchgate area. Luckily the Presbyterian Meeting House in Churchgate Street was unscathed, although it would be rebuilt in 1711.

In 1707, the "Fundamental and Standing Rules and Orders for the Charity Schools in St EdmundsBury in Suffolk", were published. These began "Whereas several schools have been lately set up and established by the voluntary subscriptions of charitable and well disposed persons in the several parishes of this town, for instructing poor children, whose parents are not able to afford them education, and for qualifying them to get their living; and for as much as good government conduces to those ends, the following Rules and Orders are by the said subscribers directed and appointed to be observed."

The boys wore green caps and neckcloths, the girls wore Dolphins with green worsted or taffety. Only Thursday afternoons could be for play, but this was "by no means to be grant(ed) too frequently". They would break up three times a year at the usual festivals, "and so by no means at Bury Fair, beginning on the Festival of St Matthew."

Queen Ann had cancelled her planned Easter visit to Newmarket in 1707, but from 30th September to 17th October, she managed an 18 day stay. This was to be her last visit to Newmarket before her death in 1714.

|

|

Northgate Street

Northgate Street

|

|

1708

|

By this time Suffolk had become a Tory electoral stronghold. One exception was the election of 1708, when a Whig majority won in Suffolk. There had been an abortive Jacobite rising in Scotland, and the resulting wave of anti-Jacobite feeling caused the Whig majority.

This was an aberration as the other four elections under Queen Anne were Tory wins in Suffolk.

|

|

Title page to Battely's 'Antiquities'

|

|

blank |

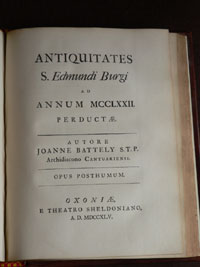

Dr John Battely had lived from 1646 to 1708, and was born and educated at Bury , eventually becoming Archdeacon of Canterbury. He was the son of an apothecary in Bury St Edmunds, and had two brothers, Nicholas and Thomas. All the boys attended the King Edward VI Grammar School at Bury and then Trinity College, Cambridge. John became Chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury, and then Archdeacon of Suffolk. In 1688 he became Archdeacon of Canterbury. He owned a house and an estate at Chevington which was left to him by his Godfather.

During his lifetime he wrote the first history of Bury St Edmunds, but it had never been published. His Opera Posthuma or Posthumous Works of John Battely would not be published until 1745.

When he died he left the estate to his brother Charles, but the income from the farm was to go to "the benefit of the poor of St Edmundsbury as are of good life and honest frame conformable to the Church of England as now by law established."

The house survives today in Depden lane, Chevington, and is known as "Batley's," but before the 1930's was known as Hole Farm.

At Rushbrook Hall, the Jermyn male line came to an end with the death of Henry, third Lord Jermyn. Henry had succeeded his brother Thomas as 3rd Baron Jermyn in 1703, and died in 1708. As he left no children by his wife, Judith, daughter of Sir Edmund Poley, of Badley, Suffolk, his titles became extinct at his death.

The eldest daughter of Thomas Jermyn had married Sir Robert Davers of Rougham. The Davers family had made a fortune in Barbados, and Sir Robert decided to buy up the remaining Rushbrooke interests of his wife's four sisters. His second son was named Jermyn Davers, and when he became the fourth baronet, he would be responsible for greatly enhancing the Rushbrook property.

|

|

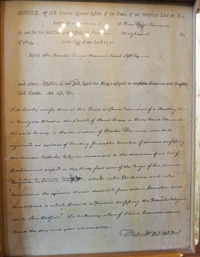

Henry Plumton's petition

Henry Plumton's petition

|

|

1709

|

Malting barley has been a local industry for centuries. It depends upon sprouting barley to generate natural sugars, but it must then be heated to prevent the growth process from consuming all the sugar. This heating has often resulted in fires breaking out within the maltings buildings. One such incident is shown here.

The illustration is of a printed petition of Henry Plumton of Ousden, Suffolk, although here it is spelled Owsden. He is requesting charitable assistance after a fire destroyed his maltings at Chevington and 'at least four hundred combes of good malt and barley'.

Plumton had lost not only his own business, but had also not paid for the barley which was destroyed. He estimated his loss at £300, and would be imprisoned if he could not raise the money. A list of locally prominent people attested to his loss in the petition.

Arundell Coke owned the manors of Murrells at Little Livermere, and Broom Hall at Great Livermere. In 1709, Coke sold the combined estates of 2,000 acres to Thomas Lee of Kensington, for £7,500. The sale encompassed the manors of Murrells, Broom Hall, 15 messuages, 2 dove houses, 6 gardens, 6 orchards, 600 acres of (arable?) land, 100 acres of meadow, 250 acres of pasture, 1,200 acres of heath, and the advowson, or living, of Little Livermere church. Lee's family had also owned Lawshall since well before 1605, when Sir Robert Lee, former Lord Mayor of London, left it in his will.

|

|

1710

|

The Manor House at Ickworth, standing to the south west of Ickworth Church was demolished. Before the Hervey Family moved out they had fitted out one of the best of the estate farmhouses to be a temporary home. This farmhouse became called Ickworth Lodge and is still in existence today. It was also useful that it was out of sight of the demolition work and intended rebuild on the Manor House.

John, the Baron Hervey, probably intended to build his new house near the old site, as his walled garden, summerhouse and canal were already there, but this never happened. The family would remain at Ickworth Lodge until the great Ickworth House was finally completed in 1829, after several more generations.

The reason for this is unknown but it is suggested that money became short because of the profligacy of his many sons. In any event after he married his second wife, he would build her the new Manor House in Schoolhall Street in Bury, and less time was spent at Ickworth.

Holy Trinity Church at Long Melford is one of the great Suffolk wool churches and was built almost entirely in the 15th century at a time of growing prosperity among the local cloth merchants. Around 1710 the tower was struck by lightning and had to be demolished. It would be replaced by a brick built tower of a classical style in 1725.

Although Queen Anne had not been at Newmarket since 1707, in 1710 she endowed the sum of £50 a year to provide two schools in that town. These were to be for 20 boys and 20 girls to learn to read and write, cast accounts, and for the knowledge and practice of the Christian Religion. The school seems to have been set up in St Mary's church, which still apparently receives annual donations from the Queen today.

|

|

Sicklesmere Toll Bar built c1762

Sicklesmere Toll Bar built c1762

|

|

1711

|

In 1555 each parish was given the responsibility for the upkeep of roads within its area. This system was bound to fail as traffic exceeded their ability to meet the ever rising costs of maintenance. In 1663 a Turnpike Authority was set up on part of the Great North Road, and after 1706 other trusts were set up.

The first Turnpike Trust in Suffolk took over the Ipswich to Scole road in 1711 and 1712, and at least part of the Ipswich to Bury road, as far as Stowmarket. It is not always possible to tell exactly when a road was "turnpiked", and this uncertainty applies to the Stowmarket to Bury Stretch of this road. Other roads to and from Bury were not turnpiked for another 50 years, the next being Bury to Sudbury in 1762.

The Trust would undertake to improve the designated road and to properly maintain it. In return the Trust could recover its costs by levying a toll on the road users. The toll was collected at tollbars located at strategic points along the route.

Meanwhile, Henry Ashley was dredging the River Lark, and building locks and staunches, in order to turn it into a commercial navigable waterway. Old established wooden bridges had to be raised in order to allow the passage of barges beneath them. By 1711 Ashley was working at Temple Bridge at Icklingham. However, he was often at the mercy of local landowners. Temple Bridge had existed in various forms for several hundred years, and the maintenance of it was shared between the adjoining estates by long precedent.

Ashley not only paid for the newly raised bridge himself, but had to agree to bear half of the costs of future maintenance before they would allow him to touch the bridge.

|

|

Presbyterian Chapel

|

|

blank |

The Unitarian Meeting House was built in Churchgate Street for local Bury presbyterians, and remains one of Bury's more remarkable buildings. It replaced an earlier Meeting House built for the Presbyterians. Unitarianism was not embraced until 1801.

In August 1711 the town of Lavenham suffered an outbreak of smallpox, which continued into 1712.

|

|

1712

|

From August 1711 to November 1712 the town of Lavenham recorded 259 burials, or about six times the normal average according to Betterton and Dymond. The cause was smallpox, and it needed an appeal throughout West Suffolk to raise a subscription for the relief of the town.

Newspapers are taken for granted today, but ever since printing was invented the crown or government had tried to restrict the publication of news and comment to avoid criticism. In 1712 attempts to license publications were replaced by placing a tax on every copy of a newspaper that was sold. The Stamp Act of 1712 would last for 140 years, with the rate of tax, or stamp duty, varying with the times. At first the rate was a halfpenny per copy, and a red stamp had to be attached to every copy to show that the tax had been paid. This forced the price of the paper to be increased to cover the tax levied. Nationally about 70 papers closed down, but some were replaced by pamphlets, or part works which included news. In 1757 the Stamp Tax was doubled to a penny a copy, and it increased to a penny halfpenny in 1776, and tuppence ha'penny by 1797 and fourpence in 1815. In 1855 when the Stamp Act was finally repealed, many new papers sprung up, often calling themselves a Free Press.

|

|

Flag of the 12th of Foot

|

|

1713

|

From 1712 to 1720 Colonel Livesay's regiment was forming part of the garrison on Minorca. In the second year of this tour of duty it received the designation, 'Twelfth Foot'. This name would stick to the regiment for the rest of its existence, even when it became the 12th (East Suffolk) in 1782, and the Suffolk Regiment in 1888.

Sir John Hervey of Ickworth had been a supporter of the 1688 revolution and in 1713 also supported the Hanoverian accession.

|

|

1714

|

The Act of Settlement of 1701 had named the Electress of Hanover, Sophia, as heir to the throne, together with her Protestant heirs.

Sophia died on 8 June 1714, before the death of Queen Anne on 1 August 1714, at which time Sophia's son duly became King George I and started the Hanoverian dynasty. He was 54 years old.

Due to bad weather, he did not arrive in Britain until 18th September.

Sir John Hervey of Ickworth had been a supporter of the 1688 revolution and in 1713 also supported the Hanoverian accession. He was at Greenwich in September to welcome the new King George I into the Country. George was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 20th October.

Lord John Hervey had been a Baron since 1703, and was now made the First Earl of Bristol for his support of the Hanoverian claim to the throne.

By this time the Bury Fair was less important as a market for merchandise, and more important as a "market for ladies".

John Eastland, a dancing master, bought the large house at the end of Angel Hill, and converted it into an Assembly House. Today this building is called the Athenaeum, but it has performed a similar public function ever since. It had been one of the largest private houses in Bury, for it had 17 hearths recorded in the Hearth Tax returns of 1674. It was on three floors at this time and Eastland had his ballroom on the second floor. The gentry would pay a subscription to use the place, and assemblies were regularly arranged. In 1715, John Hervey the first Earl of Bristol, recorded that he had paid his subscription to Mr Eastland's New Rooms in Bury. The building would stay in this form until 1789, when the ballroom was removed to the Ground Floor, as it is today.

|

|

1715

|

Since 1688, most electorates had grown in size. Suffolk County had 4,500 voters in 1673, which had grown to 6,500 by 1715. The qualification to vote for the two County MP's was to own a Freehold worth 40 shillings or more. These were called the 40 shilling freeholders.

In addition certain boroughs could also send MP's to Westminster. In most of the Boroughs in Suffolk, like Ipswich, Eye and Sudbury, voters had to be Freemen of the Borough. Ipswich had 600 freemen, Eye had 200 and Sudbury had 800, all voters.

In Bury the position was different. Only the members of the Corporation could vote for the two Borough MP's, so the parliamentary electorate in 1715 was 37, the same as in 1690, and the same as in 1614.

However, there were at least 282 40 shilling freeholders in Bury who voted in the county elections for parliament in 1710, irrespective of their rights in the borough election. These included small tradesmen as well as the more wealthy.

There were ten general elections between 1694 and 1715. The seven Suffolk Boroughs returned 14 Mp's and the County had another 2, making 16 Suffolk MP's in all.

Thomas Lee, the owner of Murrells manor and Broom Hall manor, covering some 2,000 acres at Little and Great Livermere, respectively, bought even more land at Great Livermere in 1715.

Suffolk's first newspaper began in about 1715. It was the "Suffolk Mercury or St Edmundsbury Post", published by Thomas Bailey. Its earliest known copy is dated 1st May, 1717, and was numbered issue 46. The printing press was located somewhere close to the Market Cross in Bury St Edmunds, but soon moved to Long Brackland, and later shifted homes again. Pat Murrell has suggested that the reason the first local press was in Bury St Edmunds, rather than in Ipswich, was that Bury was a fashionable town, which was home to many of the gentry, with the means and inclination to afford a regular supply of mainly London news. The Jacobite Rebellion of 1715 led to a thirst for news of the progress in suppressing the uprising. Circulation might have been 200 to 250 copies only. The Suffolk Mercury would last until about 1740.

|

|

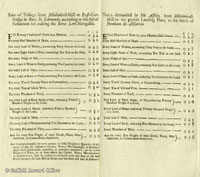

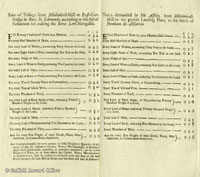

Ashley's tolls for using River Lark

Ashley's tolls for using River Lark

|

|

1716

|

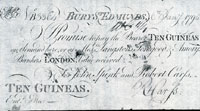

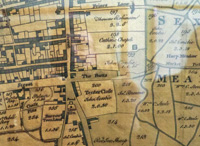

The Lark navigation was now open for business from Mildenhall to Bury St Edmunds under an Act of Parliament passed in 1699/1700. By 1700 the River Lark was no longer navigable any further than Mildenhall from the sea, and so Henry Ashley obtained the Act to allow navigation as far as Eastgate Street. The Corporation of Bury were afraid of him setting up a wharfage monopoly, and opposed the plan. All Ashley could do was build his canal as far as Fornham, outside the Borough boundary.

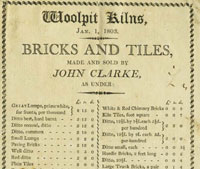

Ashley's list of charges for moving loads along the new navigation are shown here. As usual, click on the thumbnail to enlarge it. He shows two lists on the page. One is for delivering the goods from Mildenhall Mill to Eastgate Bridge, "according to the Act of Parliament", and is on the left hand side of the page. The list on the right is for deliveries to "the present landing place in the parish of Fornham St Martin." Coal, timber, wool, salt and grain are at the head of the lists, possibly reflecting the expected traffic somewhat.

It is also interesting to note that quantities are defined by what it was practicable to count during loading. We would weigh coal by the ton and hundredweight, but here it is measured in "chaldrons", as defined at Kings Lynn; the "Lynn measure".

|

|

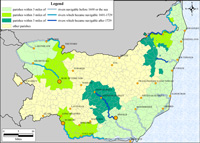

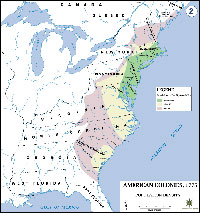

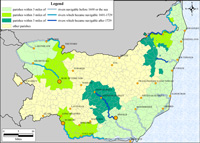

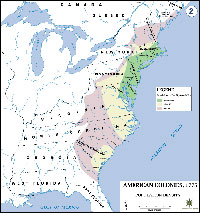

Suffolk navigable rivers

|

|

blank |

This map by Cambridge University shows the impact of improved navigable rivers on adjacent parishes. It shows how many parishes would be within three miles of the navigation once the river Lark (and others) was improved. Lark navigation account books tell us of the many stop-off points that were available along the river to unload cargo. The poorer rural areas were unlikely to unload coal, as it was too expensive, and peat turves were a cheaper alternative. Often public houses would set up and establish small piers to offload deliveries.

The canal seems to have been profitable immediately, largely for bringing in coal to Bury St Edmunds. Between 1716 and 1855 the River Lark was a busy waterway linking Bury St Edmunds with Ely, Cambridge and Kings Lynn. Boys in the 1960's still called the River Lark behind the Mildenhall Road, "the Coal Rivers".

A new purpose built church was completed for the Congregationalists in Whiting Street.

The Hervey family had owned Ickworth manor since 1467. The family had grown in power, influence and wealth by this time and John Hervey, since 1714 the First Earl of Bristol, bought the manors of Hargrave and Chevington from Sir William Gage of Hengrave for £10,942.8s.5d. He also began to plant up the woods and trees which surround Ickworth Park today.

|

|

1718

|

Between 1715 and 1718, Dr John Evans collected details of every Dissenting congregation in England and Wales. Since 1689 Dissenters could worship in public, resulting in a large increase in their numbers. Bury now had 900 Protestant Dissenters by 1718 compared to 167 in 1676. Haverhill had 250 compared to 30 in the Compton census. Clare had 400 compared to a very high 300 in 1676. Sudbury had 400 now and 100 in 1676.

Walsham le Willows had grown from only 3 to 400, and Wattisfield from 49 to 350.

Numbers attending Anglican services had declined, but under the Toleration Act of 1689, people could now avoid church attendance altogether if they wished.

Samuel Tymms recorded an outbreak of smallpox in Bury in 1718.

|

|

1719

|

The West Mill was built on Horringer Road at Bury St Edmunds by the Woodruffe family. It was built overlooking the Linnet valley to catch as much wind as possible. A John Woodruffe was recorded as running the mill in 1791. This mill stood until 1801 when it burnt down. It would be rebuilt the following year, and lasted until 1918 when it was demolished. This mill was only one of about 60 mills recorded in Bury St Edmunds over the centuries, but West Mill was one of the most successful and long running businesses.

|

|

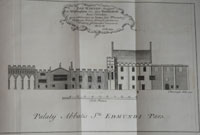

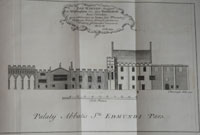

The Abbot's Palace

|

|

1720

|

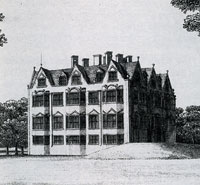

In 1720, Major Richardson Pack bought the Abbey precincts, including the Vinefields, but excluding the Great Cemetery. The price in 1720 was recorded as £2,800. The Abbot's Palace had been refurbished, which explains the high price. However, Major Richardson Pack was obviously unimpressed, as he was the man who demolished the Abbot's Palace.

Richardson Pack (1682–1728) was an English professional soldier and writer. He was born at Stoke Ash in Suffolk of good family. His father was High Sheriff of Suffolk in 1697. Although he trained as a lawyer, he threw it in to join the army. Following campaigns abroad he came back to England, and after a time he moved to Bury St Edmunds. At Bury, in the spring of 1724, he was dangerously ill, but recovered under the care of Dr. Richard Mead. Early in 1725 he moved to Exeter, but he followed Colonel Montagu's regiment, in which he was then a major, when it was ordered to Aberdeen. He died at Aberdeen in September 1728.

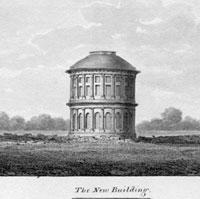

The mansion in the abbey grounds,lived in by Sir John Eyer in the late 16th century, and now known as the Abbot's Palace, was demolished on Pack's orders. The picture shown here is of the Abbots Palace drawn in 1720 by J Burrough, the year in which the palace was demolished. Sir James Burrough was a well known antiquarian and amateur architect in the area. He lived from 1691 until 1764, and was the Master of Gonville and Caius College at Cambridge from 1754 until his death. He himself had amassed a collection of notes and drawings on the antiquities of Bury, which he would leave to the library of St James's Church. This picture was published in Dr Batteley's 'Opera Posthuma' of 1745.

Thomas Lee owned well over 2,000 acres around Great and Little Livermere by this time, including the manors of Murrells and Broom Hall. In 1720 he died, and left all his property to his son, Baptist Lee. Little Livermere probably included the an early version of Livermere Hall at this time, as Roberts considered that its central core was characteristic of the late 17th century. Nevertheless, Baptist Lee would own the property until his death in 1768, and in his later years he would make substantail alterations to the Hall and the landscape around it.

The Ipswich Journal began life in about 1720, and was a new rival for the existing Suffolk Mercury, published by Thomas Bailey at Bury St Edmunds. The Ipswich Journal was published by John Bagnall, a London printer who had moved out to Ipswich. It came out on a Saturday, and would survive under various owners until the 20th century. It became the Ipswich Gazette in 1734.

|

|

1721

|

A major financial crisis occurred with the bursting of the so-called South Seas Bubble in September. Many investors who had overstretched themselves now faced ruin. One such man was Arundel Coke of Honey Hill, Bury St Edmunds, of whom, more will be heard later.

In Bury there was an enquiry into a supposed Right of Way from Lower Baxter Street to the Angel Hill. Obviously by this time any such access must have been no longer self evident, but it is entirely possible that the original street pattern had included a street, or alleyway off the corner of Angel Hill, between the Borough Offices and number 8 Angel Hill, also called the Angel Corner. The building of the house at Angel Corner in 1702 may have obstructed this access.

There are records which tell us about the Coaching services running out of the Greyhound Yard on the Buttermarket in 1721. The Greyhound was on the site of the Suffolk Hotel, which replaced it during a rebuild in 1833. In 1721 the coach ran to and from the Vine Inn in Bishopsgate Street in London, once a week. It stopped overnight at the White Hart in Braintree, showing that it took two days to travel from Bury to London at this time. Goods travelled by the more cumbersome waggons of the day, and took a day or two longer. A one day coach would not arrive in Bury until 1737, when the Angel started a new service.

|

|

Arundel Coke's House

|

|

1722

|

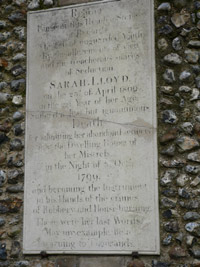

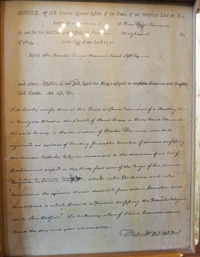

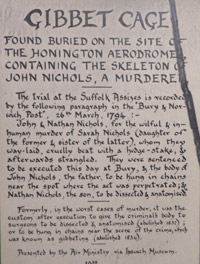

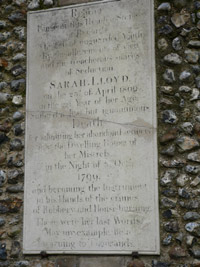

A highly publicised trial took place of Arundel Coke, who lived in Honey Hill, Bury St Edmunds. Coke was a barrister, but lived a flamboyant lifestyle, and was always short of money. His home was right next door to the Manor House, and is a stone clad house which today is called St Denys. He was also one of the Guildhall Feoffees, and a pillar of local society. He had been facing ruin following the financial crisis known as the South Sea Bubble. He believed that if his wife's brother were to die, his wife would inherit his fortune. The brother in law was Edward Crisp, who lived in a very fine house at number 6, Angel Hill, which is today the Tourist Information Office.

Coke hatched a plot to hire a ruffian called Woodburn, who was also a local handyman, to murder Crisp. Following a New Year Dinner party at his house, Coke took Crisp through the Great Churchyard on the pretext of visiting Mrs. Monk's Coffee House. Woodburn then attacked them with a knife. Coke ran off, leaving Crisp to his fate, but Woodburn bungled the attempt and only managed to slash open Crisp's nose.

They were tried at the Assizes, in the Court of Common Pleas, at Bury. On 13th March 1721, they were found guilty, and sentence was passed the following day.

Both Coke and Woodburn were hanged after Coke confessed to the plot.

This case illustrates the problem that modern people can have with the dating systems in use in the past. Until 1751, the year began on Lady Day, the 25th March. From 1st January 1752, the year began on 1st January, a practice already in use on the continent. Therefore the date known at the time as 13th March 1721, to modern eyes would seem to be properly called 13th March 1722.

Dates have been "adjusted" like this over the years by later writers, and sometimes have got adjusted more than once, so that this trial has been written up as happening in 1721 or 1722, or even 1723. Does this matter? Yes it does matter if we are looking to follow the sequence of events, or the cause and effect. To modern minds the events of January, February and March 1721 are assumed to have taken place before the events of April to December, 1721. But to the person in 1721 they naturally took them to occur after April to December.

|

|

The Priory by 1907

|

|

blank |

Henry Ashley, the builder of the Lark Navigation, had now apparently accepted that he had to make his permanent terminus at Fornham, just outside the boundary of the Borough of Bury St Edmunds. He bought the Priory Estate from Bridget Short, consisting of 8 acres including Babwell Fen meadows and Bell Meadow.

This purchase included the site of the Franciscan Friary which was dissolved around 1538. Henry Ashley is thought to have built the mansion now known as the Priory, probably incorporating some features of the remaining remnants of the friary buildings.

|

|

1724

|

Daniel Defoe wrote his "Tour through the Eastern Counties" covering the years 1724 to 1726 and described Bury at the time as a major social capital. Its old cloth industries had long gone. The weaving of darnex coverlets was declining and only spinning remained as a major manufacture. "The beauty of this town consists in the number of gentry who dwell in and near it, ..... the affluence and plenty they live in". Bury fair attracted people for "the company", not for the trade. It was also called, "The Montpelier of Suffolk, and perhaps of England". Repeating earlier writers, he described the "pleasant situation and the wholesome air." Bury was "crowded with Nobility and Gentry."

Although Ipswich was far larger than Bury at this time, Defoe commented that "there were not so many gentry here as at Bury."

Suffolk had been an important textile manufacturing region since the Middle Ages, but by this time very little cloth was made in the County. Sudbury and Long Melford still made says and perpetuanas, and this would carry on for the next sixty years. Calimancoes were made in Lavenham, tammies in Stowmarket, and bays and says in Nayland.

Defoe described Sudbury as "remarkable for nothing except for being very populous and very poor."

Mostly, however, weaving was replaced by wool combing and yarn spinning for the worsted makers in Colchester and Norwich, and Bury was a growing centre for these trades.

By 1724 the Little Livermere estate was owned by Baptist Lee. Accounts differ as to whether he inherited it from his father, Thomas Lee, in 1720, or whether it was purchased in either 1722 or 1724, possibly from the Duke of Grafton. W M Roberts wrote that he could find no evidence that the Duke of Grafton ever owned this property.

|

|

Abbot's palace in 1725

|

|

1725

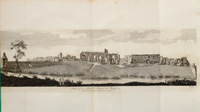

|

This picture of the ruins of the Abbot's palace in the grounds of the Abbey of St Edmund was taken from a watercolour painted in 1725. It was engraved for printing by R Godfrey in 1779. If you click on the thumbnail to see the full picture, it shows the dovecote on the extreme left which can still be seen today. It also shows one arm of the River Linnet flowing immediately in front of the dovecote. At this time the Lark and the Linnet ran parallel to each other until they joined at the Abbot's Bridge.

|

|

Melford church tower 1725-1903

|

|

blank |

Holy Trinity Church at Long Melford had suffered a lightning strike to its medieval tower around 1710, and was subsequently demolished. This tower was rebuilt by 1725 in the new classical style in brick. The main part of the church had been completed in 1484, the Lady Chapel in 1496, and the Clopton Chapel was from about the same date. Parts of the west end were even older than this, and the style of the new tower was a bold contrast to the Gothic whole. The tower of 1725 would itself disappear from view in 1903, when it would be enclosed within a neo-Gothic exterior. The 1725 tower can be seen in this Fred Watson photograph taken some time before the 1903 rebuild.

|

|

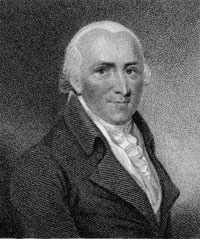

Sir William Gage 2nd baronet c1688

|

|

blank |

Dr Francis Young has discussed the origins of the greengage in England and concluded that around 1725 the second baronet of Hengrave, Sir William Gage, (c1650-1727) did indeed introduce this plum to England from France. The earliest source that he found was the reminiscences of the horticulturalist Peter Collinson (d. 1760), published in 1843. Collinson recorded that,

"I was on a visit to Sir William Gage at Hengrave, near Bury; he was then near 70; he told me that he first brought over, from France, the Grosse Reine Claude, and introduced it into England, and in compliment to him the plum was called the Green Gage; this was about the year 1725."

Mr Young also recorded a later account, which he regarded as "retrospectively invented aetiology":

"In 1812 Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820) wrote the following in Transactions of the Royal Horticultural Society, vol. 1, Appendix, p. 8:

'The Gage family, in the last century, procured from the monks of the Chartreuse, at Paris, a collection of fruit-trees: these arrived in England with the tickets safely affixed to them, except only the Reine Claude, the ticket of which had been rubbed off in the passage. The gardener being, from this circumstance, ignorant of the name, called it, when it bore fruit, the Green Gage.'"

|

|

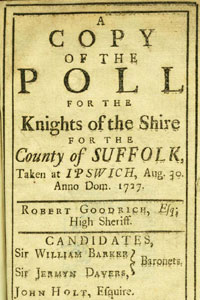

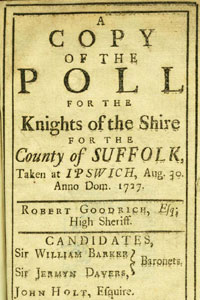

County Poll 1727

|

|

1727

|

This illustration is of a book printed by John Bagnall which records several Suffolk County polls or elections, starting with that held on 30th August, 1727. It lists, in alphabetical order the villages and towns, and the voters' names and an initial indicating the vote cast. The candidates were as follows: Sir William Barker, Sir Jermyn Davers, both baronets, and John Holt Esq. At this time every voter's name was public knowledge, together with how they had voted.

On 11th June, King George I died. Within a week John Hervey, First Earl of Bristol, had visited the new king to ask for preferment for his son John, styled Lord Hervey of Ickworth. After King George II took the throne, Lord Hervey was made the King's Vice Chamberlain.

John, Lord Hervey, was the first son of Lord Bristol and his second wife, Elizabeth Felton. They had married in 1695, and John was born in 1696. He became a very well known politician and pamphleteer, of the Walpole faction. Eventually he became Lord Privy Seal. He was close to Queen Caroline and George II. His nature led Lady Mary Wortley Montague to conclude that there were three types of human species, "men, women and Herveys." He married Molly Lepel, a court beauty, and had eight children. As he died eight years before his father at the age of only 47 in 1743, he never inherited the Earldom. His sons, however became 2nd, 3rd and 4th Earls after 1751.

The Great Court of St Edmunds' Abbey was acquired by the Davers family.

In 1727 the tenancy of the Queens Head, "a good accustomed ale house in the Churchgate Street, Bury St Edmunds", was advertised. It had once been known as the Norfolk Coffee House, but must have been an ale house latterly. It was one of three licensed premises owned by the Guildhall Feoffees, who rented them out to suitable tenants.

|

|

Tregonwell Frampton 1641-1727

|

|

blank |

Tregonwell Frampton died at Newmarket in 1727. He was born in 1641 in Dorset, and spent his early life pursuing the sport of hawking or falconry. Once horse racing became popular, he came to Newmarket in, or just before, 1675, to place large bets on the outcome of races. He quickly became a well known high stakes gambler, a skill which relied upon a detailed knowledge of breeding and form, in which he was expert. By 1695 his knowledge led him to being described on his tombstone as ‘keeper of the running horses to their sacred majesties William III, Queen Anne, George I and George II.’

Frampton kept this post to his dieing day, which was 12 March 1727. He was buried in the church of All Saints, Newmarket, where on the south side of the altar was a mural monument of black and white marble inscribed to his memory. In prints made of a portrait of him by John Wootton, dated 1791, he was described as ‘the father of the turf.’ His drab clothing and unprepossessing appearance was a feature of him all his life.

|

|

1729

|

Possibly one of the ceremonial maces owned by Bury St Edmunds Borough Corporation was damaged around this time as one of them has a shaft which was cast new in 1729. The corporation paid £25 17s 6d for the repairs.

|

|

1730

|

The firm of Orbell Ray in Bury St Edmunds must have been of considerable size, even at this early date, as Ray insured his goods and stock in trade at £500. This was a sizeable sum for a provincial town, and we must remember that it was normal to be considerably under insured at the time. The stocks would have been wool and yarn.

Around 1730 Sir John Cullum, the fifth baronet of the family which had owned Hardwick and Hawstead since 1656, finally seems to have moved completely from Hawstead Place into Hardwick House. Sir John was married to Susanna Gery, daughter of Sir Thomas Gery, and thus did Gery become a Cullum family name, surviving in usage into the twentieth century.

Henry Ashley junior was born in 1654, the son of Henry Ashley, (1630-1700), a tanner from Huntingdon who had leased the navigation of the River Great Ouse. Henry junior had taken over from his father, and made improvements to the Ouse, and in 1699 had been the promoter of the Act to provide the Lark Navigation. By 1730 the River Lark was a thriving canal enterprise for Ashley.

In 1730 Henry Ashley junior died, and in his will he divided his estate between his two daughters.

Part passed to his daughter Joanna, who was married to a Joshua Palmer, and part to another daughter married to a Mr Burch. Unfortunately they could not agree who got which assets, and from 1730 until 1742 there was a protracted legal dispute over the rights to the River Lark as well as other property. Not until 1842 was judgement concluded which gave the Lark to the Palmers. The Lark navigation would continue within the Palmer family for the rest of the century.

|

|

1731

|

In 1731 Samuel Kent, a London distiller, bought Fornham St Genevieve as a country estate. The Fornham estate had been owned by the Kytson family of Hengrave Hall since 1541. It passed into the hands of the Gage family, and then to the Gipps family before being bought by Kent. Samuel Kent was a wealthy London malt distiller. He would start to build Fornham Hall, and lay out Fornham Park.

This work must have continued fitfully over the next 50 years, and it is unclear which member of the family was most responsible for it. The story becomes very obscure because upon Kent's death the estate passed to his son in law, Sir Charles Egleton. Egleton had already bought land at Fornham St Martin. He was a London Goldsmith who would die in 1769 and leave Fornham St Genevieve to his son Charles. Charles Egleton changed his name to Charles Kent, and was knighted, becoming Sir Charles Kent in 1782. It is usually said that this Sir Charles Kent was really responsible for the building of Fornham St Genevieve Hall.

It is reported that during 1731 the tomb of Mary Tudor, located within St Mary's church in Bury St Edmunds, was opened to reveal a leaden coffin. A plate upon it read, "Mary Quene 1533 of ffrance Edmund S"

Until 1731 Hugh Owen was the only Catholic priest in Bury St Edmunds. Dr Francis Young has established that "in that year a Benedictine monk, Alexius Jones, arrived to serve as chaplain to the Bond family, who lived in Eastgate Street in a house that was sadly knocked down during road-widening in the 1920s....

Jones posed as a tutor to the Bonds’ son Jemmy but officiated at the Mass in a secret chapel in the Bond household."

The Catholic Bond family had moved to Bury St Edmunds in 1675, following the marriage of Mary Bond to Sir William Gage of Hengrave. Her brother William had married Mary Gage at the same time.

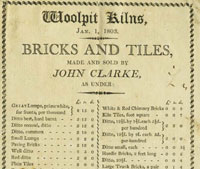

Around this time Woolpit was noted for making the best white bricks. Bricks would continue to made at Woolpit until the Second World War.

|

|

1732

|

The Earl of Oxford recorded that avenues of trees were newly planted in the Great Churchyard at Bury. There is some evidence that at first they planted Poplars, rather than the Limes of today. The Earl also provided a snapshot of the Brecklands.

The following account by the 2nd Earl of Oxford, gives a graphic description of the Breckland landscape in the eighteenth century:

|

|

Breckland sand dunes

|

|

blank |

"The next day Thursday, September the 21st, 1732, we set out from Brandon, seven long, very long miles to Barton Mills over the sands, terrible tedious travelling both to man and horse. I could not but reflect what terrible travelling it must be where the heat of the sun is intense upon the wide sandy deserts, where the poor travellers are often smothered with the sand or scorched with the sun’s heat reflected from the burning sands. We leave the sands at Barton Mills which we were very glad of. The river that runs by Barton Mills is navigable as I said to Bury. We left Mildenhall, the seat of Sir Thomas Hanmer, on the right hand, a most miserable situation. On one side he is subject to be choked with sand, on the other he lives close to a dark vile black fen which lies to the north east of him; so that he enjoys that wicked wind with the addition of the air from that fen."

This picture of Wangford Warren shows today's trees which would have been absent in 1732. Otherwise the view is the same.

Sir Thomas Hanmer, 4th Baronet (24 September 1677 – 7 May 1746) was Speaker of the House of Commons from 1714 to 1715, discharging the duties of the office with some acclaim. He was also one of the early editors of the works of William Shakespeare, but this was not published until 1744. The estate at Mildenhall had come to Sir Thomas from his step mother, who was the sister of the second Sir Henry North.

|

|

Livermere Hall c1730

|

|

1733

|

There was an English State Lottery which ran from 1694 until 1826. These early English lotteries ran for over 250 years, until the government, under constant pressure from the opposition in parliament, declared a final lottery in 1826. In 1733, it is reported that Baptist Lee, who already owned well over 2,000 acres around Great and Little Liveremere, had won £30,000 on the state lottery. This sum may be equated to over £2.5 million in today's terms. Baptist Lee now had the resources to radically improve his estates in the area.

This picture shows Lee's Livermere Hall in about 1730. The central part of the house is 17th century and the wings date from the early 18th century. The village of Little Livermere is not visible in this picture, and must have been clustered around St Peter's church off to the left of the picture. The view here is from the stream which would later be converted into two ornamental canals.

The underground Catholic Mission to Bury St Edmunds was ministered to by the secular priest, Hugh Owen, (sponsored by the Short family), and, to a lesser extent, by Alexius Jones, the Benedictine Chaplain to the Bond family. Dr Francis Young has established that another Benedictine appeared on the scene in 1733, called Francis Howard. "Howard was chaplain to the Gages at Hengrave Hall but was frequently in Bury, because the Gages owned a townhouse in Northgate Street (now the Farmers Club)."

Also, " That year a devastating smallpox epidemic swept through the town and anyone who could afford to do so fled Bury; Sir Thomas Gage and Mr Bond fled to Thetford, ostensibly on a fishing trip, and took Jones and Howard with them."

The ageing Hugh Owen was left to minister to dead and dying Catholics.

|

|

Market Cross by 1748

|

|

1734

|

Bury got its first theatre in 1734, purpose built on the first floor in the Market Cross. Converting the upper floor of the Market Cross was estimated to cost £150.

In August 1734 this playhouse was leased to George Steggould for a seven year term at £42 a year. He could put on plays during Bury Fair, from 20th September to 10th October, and also over Christmas from 26th December to 12th January. He was also allowed to run shows for a fortnight during each quarterly Assize sitting.

Performances of plays and other entertainments had previously taken place in the Guldhall and even the Shire Hall. Inn yards provided the less well off in society with the same function, but Bury Society now demanded some better facilities. The room above the Market Cross had hitherto been used as a Woolhall, or Wool Exchange, as well as for other public events, before this new work. The Woolhall was now moved down the road.

The Market Cross would be converted into the much grander structure by Robert Adam from 1774, opening in 1780, and surviving to this day.

|

|

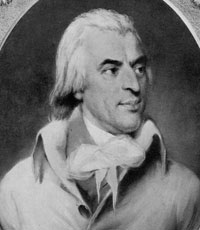

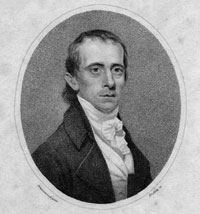

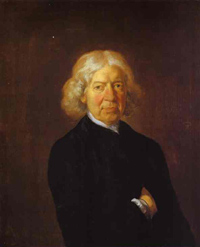

John Kirby by Thomas Gainsborough, 1753

|

|

1735

|

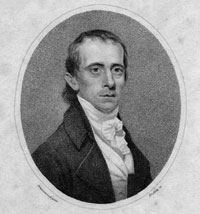

In August 1735 John Kirby published his book called "The Suffolk Traveller". He would follow this up in 1736 by publishing a one inch to the mile map of the county, followed by a half inch scale in 1737. Not much is known about John Kirby's origins, but he was known to have run Glevering watermill, near Wickham market, in Suffolk after 1714. By 1725 he had taken up land surveying, and he made measured plans for the estates of local gentlemen. This portrait of him was made by Thomas Gainsborough shortly before Kirby died in 1753, in Ipswich. Kirby had continued to improve the Suffolk Traveller after its first edition, and sold copies from a shop in Wickham Market, as well as through other booksellers. One of his sons, Joshua Kirby, was a friend of Thomas Gainsborough and that is how Gainsborough came to paint this portrait of Joshua's father.

Kirby had painstakingly raised himself from miller to surveyor, but his book and maps took years to produce. They were based upon surveys of the county by Kirby and Nathaniel Bacon made between 1732 and 1733. Some time in 1733 Bacon was replaced by Francis Emerton, a surveyor from Gillingham near Beccles, and Kirby and Emerton worked together on the survey through into 1734.

Emerton had previously been working on a similar Suffolk project for James Corbridge, who had announced his intention to survey Norfolk and Suffolk in 1727. Emerton now took the lists of subscribers for the Corbridge map, and gave them to Kirby, ensuring that the Kirby map would be the one to succeed.

Previously published maps had all been based upon Christopher Saxton's survey of 1575, and as over 150 years had passed, Kirby represented a significant updating and improvement on these earlier efforts.

In common with publishing practice at the time, subscriptions for the map were invited prior to publication, to be collected at booksellers throughout the county. In Bury these were taken by Hannibal Hall and Thomas Bailey during 1732. In 1733 Mrs Mary Watson, bookseller, was taking the Bury subscriptions. People subscribing for the maps at ten shillings per sheet received the book gratis.

The map was engraved on to four copper plates for printing by Mr Richard Collins at Bury St Edmunds. Each plate would produce one imperial sized sheet of paper.

At this time John Kirby was a little known, local surveyor living in Wickham Market. After he died in 1753 a second edition of his Suffolk Traveller was published in 1764 by John Shave, an Ipswich publisher. However, Kirby himself had always planned further editions.

The Suffolk Traveller consisted of a description of the county, followed by a series of journies between towns, in which each town or village is described, together with the route to take to the next village. After the introduction to Suffolk he starts with Ipswich and a village by village perambulation to Yarmouth. Having examined all roads out of Ipswich , he then describes the roads out of Bury, and so on.

Some of his observations on Suffolk included the following:

"This county is naturally divided into the Sandlands, the Woodlands, and the Fielding......"

Kirby's sand lands were the sandy soils of the eastern coastal strip of Suffolk, which he subdivided into marsh, arable and heath.

The woodland part included the southern part of Suffolk from the hundred of Blything as far as Haverhill, including those heavy clay parts of Thedwastry, Blackbourne and Thingoe.

"This part is generally very Dirty and Fruitful. In this part is made the Suffolk Butter, so managed by the neat dairy wife, that it is justly esteemed the pleasantest and best in England. The cheeses, if right made, none much better, and if not so, none can be worse.

The Fielding part contains all the hundred of Lackford, and the remaining parts of the hundreds of Blackbourne, Thedwastry, and Thingoe; and is most of it Sheep-Walks, yet affords good corn in divers parts."

"The ecclesiastical government is under the Bishop of Norwich, it being part of that see....it is divided into two archdeaconries, viz Suffolk containing the Eastern parts of this county, and Sudbury including the Western parts. These two archdeaconries are subdivided into 22 Deaneries.......The Deaconries in the Archdeaconry of Sudbury are, Sudbury, Stow, Thingoe, Clare, Fordham, Hartsmere, Blackbourne and Thedwastry...."

"The civil government of this county is in the High Sheriff, for the time being. The division of this county ...was formerly divided into the Geldable and the Liberties of St Edmund, St Etheldred, and St Audrey; but the present division is into the Geldable and the Franchise or Liberty of St Edmund, each of them furnishes a distinct Grand Jury at the Assizes..."

"Towards the military defence of the kingdom, this county furnishes, as its quota to the Militia, 4 Regiments of Foot, the White, the Red, the Yellow, and the Blew, each consisting of 6 companies. The White is raised in the south part, the Red in the North about Hoxne hundred, the Blew in the east about Beccles, and the Yellow in the west about Clare. There is one Regiment of Horse of 4 Troops, each severally carrying the colours of the Foot regiments, and belonging to them, and raised in the same parts of the country. The Militia is under the command of the Lord Lieutenant of the County, the Most Noble Charles, Duke of Grafton, being the present Lord Lieutenant."

The 1735 edition of the Suffolk Traveller was printed by John Bagnall at Ipswich. It contains many observations on the towns and villages of Suffolk, some of which were a bit sketchy.

Kirby gave the following description of Haverhill:

"Haverhill, or as in old records Haverhull or Haverel, is a long thorough-fare mean built town about a mile in length. The south end of the street is part in this County, and part in Essex. The north end is wholly in Suffolk. It has a mean market weekly on Wednesdays, and two fairs yearly, the one on May the 1st, and the other on August the 15th. Here is nothing in this town worthy of remark, at present: but it seems to have been larger than it is now, by the ruins of a church or chapel, still remaining."

Of Bury, Kirby wrote:

"Bury St Edmunds is situate on the west side of the River Lark, which is at present navigable from Lynn to Fornham, a mile north of the town. It has a most fruitful enclosed country on the south and south west, and on the north and north west the most delicious champaign fields, extending themselves to Lynn, and that part of the Norfolk Coast. The country on the east is partly open and partly enclosed. It is so regularly built, that almost all the streets cut one another at right angles; and it stands upon such an easy ascent that an ancient writer has recorded this encomium of it : "That the sun shines not upon a town more agreeable in its situation.

This was the Villa Faustini of the Romans, and afterwards had the name of Bedericesworth, or Beodricesworth, differently spelt by different authors, as Saxon names frequently are, and taken, if we might credit the records of the old monks, from one Beodricus, who being Lord and Proprietary of this town made St Edmund his heir.

The abbey.....".

Kirby went on to describe St Edmund's life. He spoke disapprovingly of how the Benedictines ousted secular clerics in 1020 and described how King Canute levied a tax of 4 pence on ploughland in Suffolk and Norfolk to pay for "a more magnificent church to the honour of this martyr." There is a description of the abbey and churches of Bury, together with the tombs of Mary Tudor and Roger Drury.

On a contemporary note he described St James church and wrote:

"There is in this church a convenient library, but no monument of note.

The rest of the publick buildings are the Abby Gate, which still speaks of the grandeur of the former abby; the Guildhall; the Grammar School, endowed by Edward VI; the Market Cross; the Wool-Hall; and the Shire House.

The civil government of the town is is now lodged in the hands of an Alderman, a Recorder, 12 Capital Burgesses, and 24 Common Burgesses. These have the sole right of choosing their own Burgesses in Parliament.

There are two weekly markets, on Wednesdays and Saturdays; the chief market is on Wednesday, and a very considerable one it is, well served with all manner of provisions. And three annual fairs; the first on Easter Tuesday, the second for three days before the feast of St Matthew and three days after, but this is generally protracted to an uncertain length, for the diversion of the nobility and gentry that usually resort to it; and the third on St Edmunds Day, November the 20th.

The Benefactors to this town are very numerous, and the commemoration of them is annually celebrated on the Thursday in Plough Monday Week.

The agreeableness of its situation has always induced many of the gentry to reside in this town and in its neighbourhood; and as it formerlly gave birth and education to several persons who were emminent in church and state, so it has also lately; and I hope may take its present flourishing condition as an earnest of its future prosperity and success.

Thus much for Bury St Edmunds. We will now take a journey from thence to Yarmouth.........."

A Freemasonry Lodge was established at the White Horse Inn on the Buttermarket. This inn was superceded by Bullens haberdashers in 1870, and in later years served as Purdey's Coffe Shop, Palmers Restaurant, and is now a travel agency and Burger King restaurant.

|

|

Ruins from the east - Edmund Prideaux

|

|

blank |

These sketches have been photographed by the RIBA, and the photographs are included in the archives of Historic England. They are labelled as "Bury St Edmunds Suffolk, Ruins of abbey. Drawn c1735 by Edmund Prideaux and now at Prideaux Place, Cornwall. (Date received 6.7.62)".

These sketches have sometimes been referred to as the source from which other later engravings have been made. However, they are different in several details from other engravings, and therefore do not seem to be the source attributed to Godfrey's print of 1779 by Mrs Statham on page 40 of "The Book of Bury St Edmunds".

|

|

Ruins of the great abbey church - Edmund Prideaux

|

|

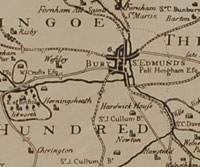

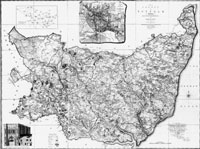

Kirby's Suffolk map |

|

1736

|

Kirby finally delivered his one inch to the mile map of Suffolk to his subscribers. They had received the accompanying book, the Suffolk Traveller, in 1735. The version shown here is a later reproduction in monochrome. This map clearly shows the Chevington Way, which no longer exists. It followed Hospital Road and Abbot Road, out of Bury, following the valley of the River Linnet, skirting around the Ickworth Estate to the west, and thence out to Chevington. When the Ickworth estate was enlarged later in the century, this route, now through the estate, would become an inconvenience to future Earls of Bristol. So from 1814 to 1823 several attempts were finally succesful in closing off this ancient routeway.

Bury St Edmunds received some fame through its MP, Lord Hervy. He was asked by the Whig Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole, to pilot the Quakers Bill through Parliament. This bill aimed to relieve the Quakers from some of their legal burdens, for which many had suffered heavy fines and long prison sentences over the years.

Unfortunately the established church were strongly opposed to it, led by the Bishop of Salisbury, who wrote a pamphlet called "The Country Parson's Plea against the Quakers Bill for Tythes." Lord Hervey wrote a reply, called "The Quakers reply to the Country Parson's Plea". He stoutly defended Quakerism, although it was not his own calling, and praised their piety, their thrift and industry, and their support of their own poor.

Lord Hervey had done his job well, and got the Bill through the House of Commons only to be defeated in the House of Lords. Bury Quakers as well as those in the rest of the country, got no relief from tithes until the late 19th century.

Hervey also started work on building a new house in Bury. It would be called the Manor House, and replaced the old Ickworth Manor House by the canal in Ickworth Park, which was demolished in 1710. The family currently resided in Ickworth Lodge.

|

|

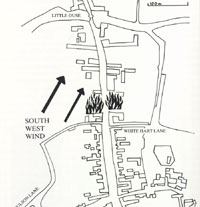

Haverhill in 1737 |

|

1737

|

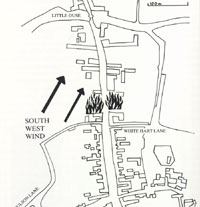

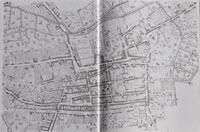

A survey of Haverhill was apparently taken in 1737. A copy resides in the Essex County Archives at Chelmsford. A redrawn copy was published in 1957 as part of the West Suffolk County Council Town Plan for Haverhill. It may not contain all the details of the original. The town was surrounded by huge open fields, and the ancient strip system is still shown as being in operation. By 1820 the Enclosure Acts would have swept this system away.

Kirby's new map of Suffolk was reissued at a scale of half inch to the mile. It was intended to be a cheaper version of the 1736 one inch map. This version of the map was engraved by Isaac Basire.

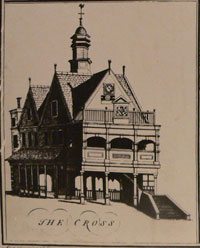

Transport from Bury to London was revolutionised when the Angel become the first of Bury's inns to run a same day coaching service to and from London. Earler services did exist, but always needed an overnight stop on the journey. The new service could reach the Spreadeagle in Gracechurch Street, London, by the late evening.

From 1737 for about a century, this one day stage coach operated from Bury to London. It ran from the Angel three times a week, and was called The Old Bury, and the Angel needed to be able to stable up to 70 horses to run her and its other coach services. The Angel was not to be the only coaching inn, as they were called, as there were several others.

The Greyhound in the Buttermarket ran a coach to London via Braintree, taking two days. The Three Tuns in Crown Street was the inn for the Norwich Mercury.

The coming of the railway would cause their final demise, but the "Old Bury" ran from the Angel Yard right into the 1840's.

As well as the glamourous stage coaches, which travelled across the country, there was a need for local travel. An inn like the Angel could also be a post house, which meant that it kept a fleet of post-chaises available to provide a local taxi service. These were driven by a post boy with two horses, available at a moments notice for hire.

|

|

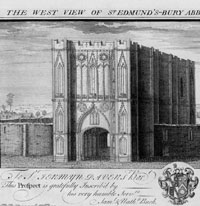

The Abbey Gate

|

|

1738

|

This picture is one of a series of engravings that Samuel and Nathaniel Buck made of British towns, castles and abbeys. Each engraving has a dedication and brief description of the place in question. The Buck brothers were important topographical artists in the 18th century. This engraving of Bury Abbey shows the Abbey Gate, and is dated 1738. The Buck brothers returned to Bury again in 1741, for another of their 'prospects'.

|

|

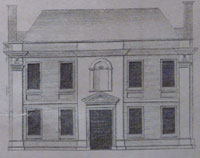

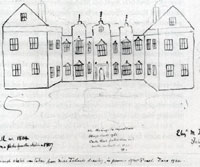

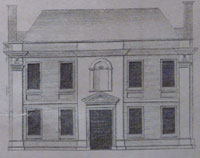

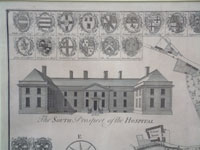

The Manor House

|

|

blank |

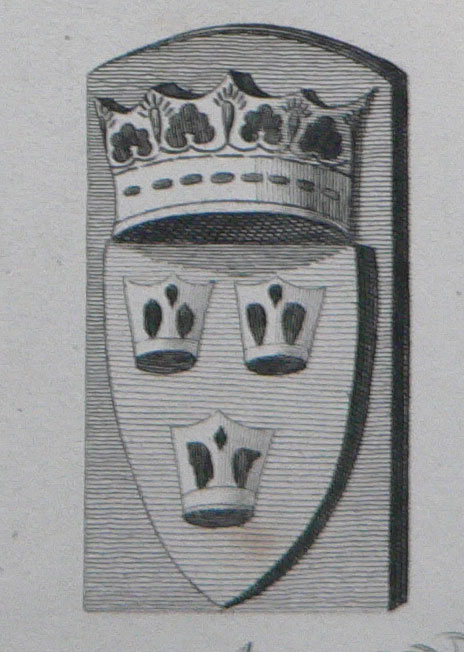

John Hervey, first Earl of Bristol since 1714, completed the two year building of the Manor House on Honey Hill for his second wife, Lady Elizabeth Hervey. She wanted to live and entertain in town during the Bury Season. The artist's impression shown here illustrates the Hervey coat of arms emblazoned on the portico. There was a dining room with Greek columns, and upstairs was a ballroom for guests to use after dining. Other rooms were also used for entertaining, but there was just one bedroom, so guests were not expected to stay overnight.

Lord Bristol had married Elizabeth Felton in 1695, and they had 16 children together, although four died in infancy and another died aged 9 years. Hervey had already had three children with his first wife, Isabella Carr. On 25th September 1738, Lord and Lady Bristol spent their first night in the new Manor House, staying until 7th October. It was designed by James Burrough, later to become Sir James Burrough. The Earl had originally intended to rebuild the Manor House in Ickworth, but now the family could divide their time between Ickworth Lodge, and the Manor House in Bury. Unfortunately Lady Bristol only enjoyed the house for three years as she died in 1741. Lord Bristol himself preferred the country home which he called "my centre of rest - sweet Ickworth."

Whether Lord Bristol ever now hoped to build a new home at Ickworth to replace the Ickworth Lodge, which he had intended only to be a temporary home, we do not know. It has been suggested that he could no longer afford yet another costly project, as his many sons were by now too great a drain on his purse. Several of his sons either were, or would become, friends of Dr Johnson. Boswell reported that Dr Johnson said of Henry Hervey, who he had met when Hervey was an officer stationed at Lichfield, "He was a vicious man, but very kind to me. If you will call a dog Hervey, I shall love him." Henry had at this time (about 1726), a house in London, where Johnson was frequently entertained, and had an opportunity of meeting genteel company. Thomas Hervey, one of the younger sons, was to give Johnson £50 in 1766, in lieu of leaving it to him in his will. These encounters were described later in Boswell's 'Life of Samuel Johnson LLD.'

Samuel Cumberland, a wealthy yarn maker of Bury St Edmunds, had insured his property with his partner, for £1,500, showing that Bury's yarn manufacturers were doing very well.

|

|

St Peter's Church at Little Livermere

|

|

1740

|

Baptist Lee owned the great house and estate at Livermere, his property covering both Great and Little Livermere. By 1740 Lee began to think about moving the village of Little Livermere to make way for the 1,000 acre Livermere Park. Baptist Lee had been the owner at Livermere since he inherited in 1720, and next door the Calthorpes of Ampton cooperated in this radical new landscape. The church remained and later its tower was raised by an extra storey to provide a fine view from Livermere Hall. The residents were provided with new estate homes elsewhere on the estate. Apart from a farmhouse, this left the church of St Peter standing isolated in the Park.

The exact date when the village was finally demolished is not clear, but baptismal records give some clues. From 1700 up to 1740 there were 24 baptisms per decade in Little Livermere church, but only three per decade in the 1750s and 1760s. From 1700 to 1750 91% of burials in the church were of persons living in the parish. In the 1750s and 1760s this had fallen to only 50%. The other 50% were presumably people born in the parish, but now located outside it.

|

|

St Peter's Church at Little Livermere

|

|

blank |

The roof of the church was removed in 1948, and it now stands as a ruin. This closer view was taken during a farm visit open day to see the lambing in progress. Livermere Hall was greatly improved by Baptist Lee, but it was eventually demolished in 1923.

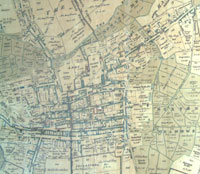

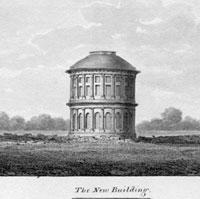

Alexander Downing began his survey of Bury St Edmunds. His idea was to invite subscriptions for a town plan in advance of publication, and he hoped to sell enough to make a profit. He would publish the resulting plan in 1741.

By the middle of the 1700's a traveller to Haverhill had noted that 'every cottage brought forth a clatter as the workers applied themselves to their looms'. The cloth produced was of the heavy linsey-wolsey variety used principally by the agricultural worker. It was towards the end of the century that the effect of the Industrial Revolution began to be felt. Master weavers began to appear, who bought up the finished cloth and marketed it, chiefly in London; woollen cloth giving way about this time to checks and fustians.

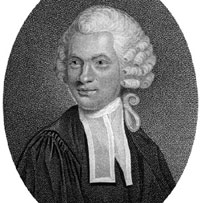

Lord Hervey of Ickworth became appointed to the high rank of Keeper of the King's Privy Seal. His own ten year old son would become the Bishop of Derry, and build the great Rotunda at Ickworth.

|

|

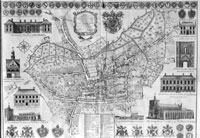

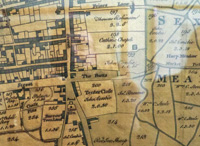

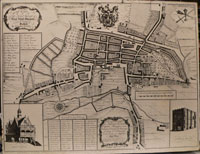

Downing's Map of Bury

|

|

| |

1741

|

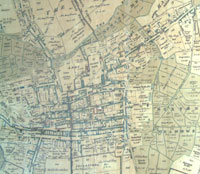

In 1741 Alexander Downing published his map of Bury, which looks very curious to modern eyes, with west at the top of the plan. A lot of the detail is heavily stylised, with gardens shown neatly laid out, the buildings shown as regular blocks in front of the gardens. The town gates are depicted but almost certainly in an idealised form, not as they really looked. The rivers Linnet and Lark were shown as still flowing in parallel through the Abbey precincts, to join just before the Abbot's Bridge.

Downing sold his map for three shillings through Wolton's of Bury.

During 1741 the Surveyors William and Thomas Warren were producing plans of the landholding of the Guildhall Feoffees. One such plan showing Moyse's Hall has the area in front of it named as Hog Hill. Today we call it the Buttermarket.

No doubt they saw Downing's map, and thought they could do a better job.

|

|

Dr Clopton's Asylum

|

|

blank |

Clopton's Asylum was shown built in the Great Churchyard in Bury, although it cannot have been finished at this time. Today it is the Provosts' house. The land was acquired by Trustees in 1735, and the fine new building seems to have been ready for its first residents in 1744. Dr Poley Clopton left money for its erection and upkeep for six poor men and six poor women who had "paid Scot and Lot without having received Parochial Relief".

Bury corporation threatened to prosecute anybody found selling Lincolnshire wool in the the two Bury wool halls without paying their market tolls. This decision was to be advertised in Stamford, Lincs, as well as in Bury on the Market Cross. This long staple wool was the basis of the high quality yarn produced around Bury at this time.

|

|

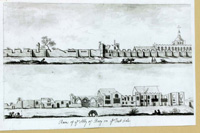

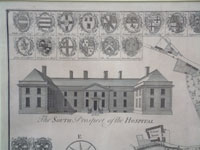

East Prospect in 1741

|

|

blank |

In 1741 Samuel and Nathaniel Buck published this engraving of the East Prospect of the town and Abbey ruins of Bury St Edmunds. Part of the King’s Topographical Collection,The East Prospect of St Edmunds Bury was released at the beginning of 1741 as part of Samuel and Nathaniel Bucks’ 'Cities, Sea-ports and Capital Towns: an important series of views showing eighty three of England and Wales’s foremost towns and cities (1728-53)'. The Buck brothers were already well known for their views of ruined castles and abbeys throughout the land.

Samuel Buck was born in Richmond, Yorkshire, in 1696, Nathaniel being a younger brother. Samuel began publishing his drawings at the age of only 15, and continued until Nathaniel died in 1754. The two brothers based themselves in London, travelling all over the countryside to draw antiquities, which they engraved during the winter months for sale as annual collections or as individual views.

The Dictionary of National Biography quotes Samuel Buck as an "engraver and topographical draughtsman, (who) drew and engraved 428 views of the ruins of all the noted abbeys, castles, &c., together with four views of seats and eighty-three large general views of the chief cities and towns of England and Wales."

In 1774 a comprehensive collection of the Bucks' work was published in 3 volumes, entitled "Buck's Antiquities or Venerable Remains of Above 400 Castles, &c., in England and Wales, with near 100 Views of Cities". The work of the Buck brothers is generally considered to be a fair and accurate copy of what they saw. Samuel died in 1779.

If you click on the thumbnail you will see the full view as published. It shows the fish ponds in the abbey grounds still visible in 1741, together with both the River Lark and the River Linnet running in parallel through the abbey grounds. The Norman Tower is shown with a pitched roof and a spire. Two windmills are visible in the distance, as is Cupola House and the Market Cross.

Mrs Statham interpreted this view as suggesting that a great deal of remains had been lost during the 1720s and 1730s. For her it cast doubt upon the accuracy of Godfrey's engraving published in 1779, which appeared to show more remains of the Abbot's Palace. In Buck's view the Palace is obscured by trees.

There was a case of arson in Crown Street, with at least two fires being laid, one of which damaged the Three Tuns inn. The Three Tuns stood where Lansbury House, once the Labour Party HQ in Bury, is now a private dwelling. The inn was not badly damaged and went on to develop as a coaching inn.

In 1741 Arthur Young, the second son of the Reverend Arthur Young, Rector of Bradfield Combust, was born at the family's London home. The child was soon taken to the Young's country home at Bradfield Hall to be raised in Suffolk. He would become famous for his writings on the improvement of agriculture, and his travels in Ireland and the Continent.